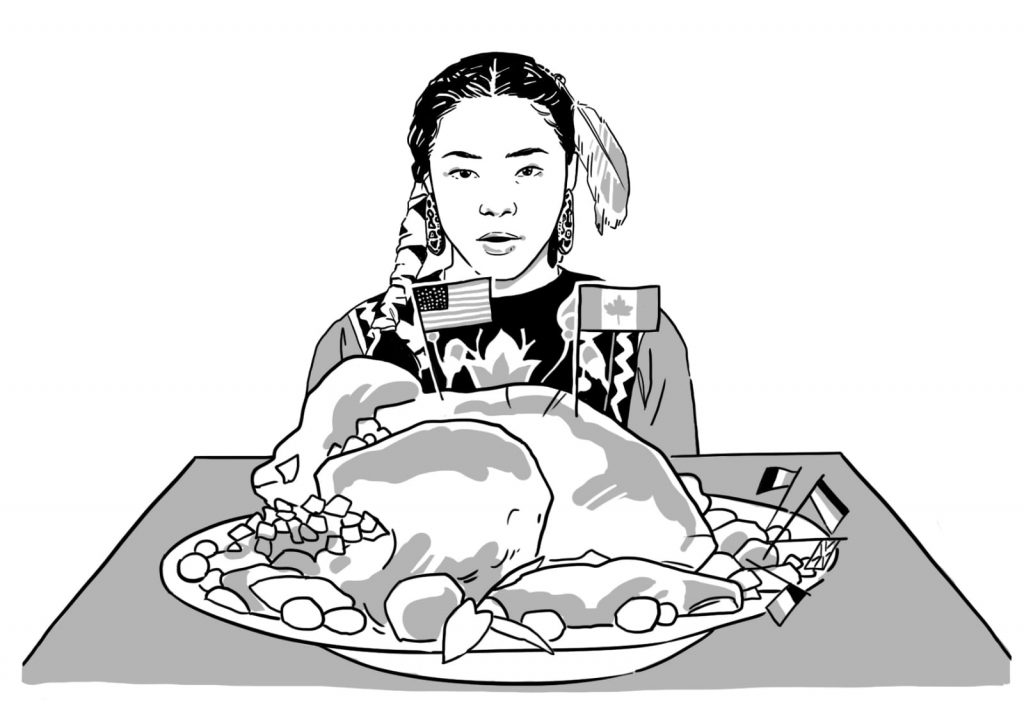

Image: Based on photographs of Autumn Peltier addressing the United Nations. She is a Canadian water activist, who comes from Wikwemikong First Nation/Manitoulin Island and is from Ojibway/Odawa heritage. The Governance Post believes that cultural appropriation and incorrect adoption or usage of elements of cultures is highly problematic.

Every autumn, North Americans gather around the table to share a meal, build community, and practice gratitude. Thanksgiving is a holiday and a tradition that is quite specific to Canada and the US. Being abroad, this year is therefore different for myself and my North American colleagues at the Hertie School. While it is one matter to celebrate Thanksgiving at home within a familiar cultural context, selling the holiday to an international audience creates an obligation for us merchants to represent it in its entirety and, particularly, its honest origins.

Thanksgiving sprung from the interaction between the settler colonies, the Indigenous communities, and the autumn harvest. The holiday developed slightly differently in Canada and the US. While both versions focus on the harvest, American Thanksgiving adds an emphasis on thanking the Indigenous communities for their grace and assistance in welcoming the settlers in a new land (to them). In hindsight, this gratitude seems rather hollow, and its annual celebration surely flies in the face of the centuries of disruption, disenfranchisement and dispossession that have been the material reality of this empty sentiment. In fact, since 1970, some Indigenous nations in America have observed a National Day of Mourning to counter-commemorate Thanksgiving from an Indigenous perspective; 2020 will be the 50th year of this protest.

Of course, gratitude is a laudable thing and practising it can be an affirmative way to connect with one’s environment and community. Research has shown that gratitude has benefits, both individually and societally. Giving, sharing, and appreciating are all practices that offer benefits to many societies. In many respects, Thanksgiving is an endeared holiday worth keeping. However, loving something does not absolve us from its history – in this context, of displacement.

As a member of a settler-colonial society, I contend that we must be honest about what we are grateful for. The issue of distributing blame for colonisation is widely debated across and within societies. In short, it is contentious because those settlers who committed the harms of colonisation are no longer alive to make amends. The debate centres on if and how today’s beneficiaries of colonial structures can and should pay for the stepping stool of dispossession they have inherited. As a point of departure, we can collectively recognise that there is blame, and it must go to someone. From there, I would argue that even though today’s residents of settler societies have not individually created this system ourselves, we each still profit from a system that structurally disadvantages Indigenous communities. Therefore, at Thanksgiving, we cannot be thankful simply for our immediate advantages at the individual level but must also understand the structural privileges we have benefited from. Perhaps with no better year in which to demarcate the shift (and despite this not being an integral part of the holiday in North America), transcending the occasion from a domestic to international setting is the perfect – if not essential – opportunity to integrate privilege checks into this tradition.

It is perhaps particularly auspicious that Europe, rather than any other continent, should be the destination for our intangible import because this continent has hosted more centres of empires than any other. A self-fulfilling consequence of this history is that European colonial powers do not share their geographic home bases with Indigenous populations. In short, the systematic invasion of others’ homes has let continental Europe remain at least one sea away from every native population that is forced to rebuild in the wake of being colonised. It is therefore even more imperative that we do not erase the legacy of disenfranchisement when bringing this colonial holiday home to roost.

What does Thanksgiving mean in Europe? A distinction between North America and Europe can be drawn by taking a comparison of Canada and Britain as a point of departure. Decolonisation and appreciation for Indigenous cultures are prioritised among progressive circles in Canada and are increasingly gaining traction in the mainstream discourse. Similarly, progressive circles in Britain have begun to tackle issues of historical disenfranchisement, challenging Britain’s history of glossing over colonialism as a thing of the past. However, the mainstream discourse has yet to catch up. The British Empire is still a source of pride in Britain, as instilled by the educational system and reinforced by government programs (for example, the Prevent programme’s emphasis on promoting “British values”; a term that has been criticised as a neutral façade for xenophobia). It seems backwards that Britain would be proud of a colonial past while Canada remains ashamed of the same colonial present. It certainly cannot be effectively argued that North American settler society as a whole is highly conscious and repentant for the foundations of our society being built on dispossession. However, in North America, proximity and shared space with resilient Indigenous nations and their cultures preclude all but the most obstinate denials that colonialism remains a foundational structure of our society. This understanding is essential to dismantling the legacies of colonisation.

While it is likely not a surprise to hear another voice clamouring for settler colonies to acknowledge and decolonise their societies, I stress that it is not work for settler-colonies alone. Europe’s lack of proximity to Indigenous populations should, in my view, be neither an absolvement of responsibility nor a base on which to ‘found’ denials of current colonial structures and the ways they govern our societies.

However, understanding is not dismantling in itself. Acknowledging the histories of trauma that Thanksgiving is built from is not going to undo colonisation. Put bluntly, lip service alone is insufficient. Words must be accompanied by actions. But how? Is it possible to decolonise Thanksgiving? Is it necessary to delete the entire holiday? Just one more example in the ongoing reckoning happening across Western societies, it is here necessary to walk an impossible line between affirmative action, dismantlement of the problematic legacy of colonialism, and the embrace of this colonial tradition. Thanksgiving need not remain a holiday so harmful that it merits a counter-commemoration just to acknowledge marginalised perspectives. What a Thanksgiving of the future looks like is unclear (although in our deliberations of this we may take some guidance from the name itself). I do not have a solution, nor do I think there is a solution. I can, however, merely defer to the voices of Indigenous peoples: to be lifted up, listened to, and acted on.

Jessie Westell is a Master of Public Policy candidate at the Hertie School of Governance with a background in Political Science and Law. She also has research experience and interests in criminology and criminal justice. Other interests include democratic participation, decolonization, privacy, and equity.