Jan-Werner Müller noted that the past returns with a vengeance in times of political crisis. How to interpret this past is, more often than not, the privilege of rulers rather than their subjects. Russian leadership, no stranger to the power of narratives, is ardently exercising this privilege. In the wake of the 2022 Ukraine invasion, the Kremlin has intensified its efforts to impose a new interpretation of contemporary Russian history to influence a new generation of citizens.

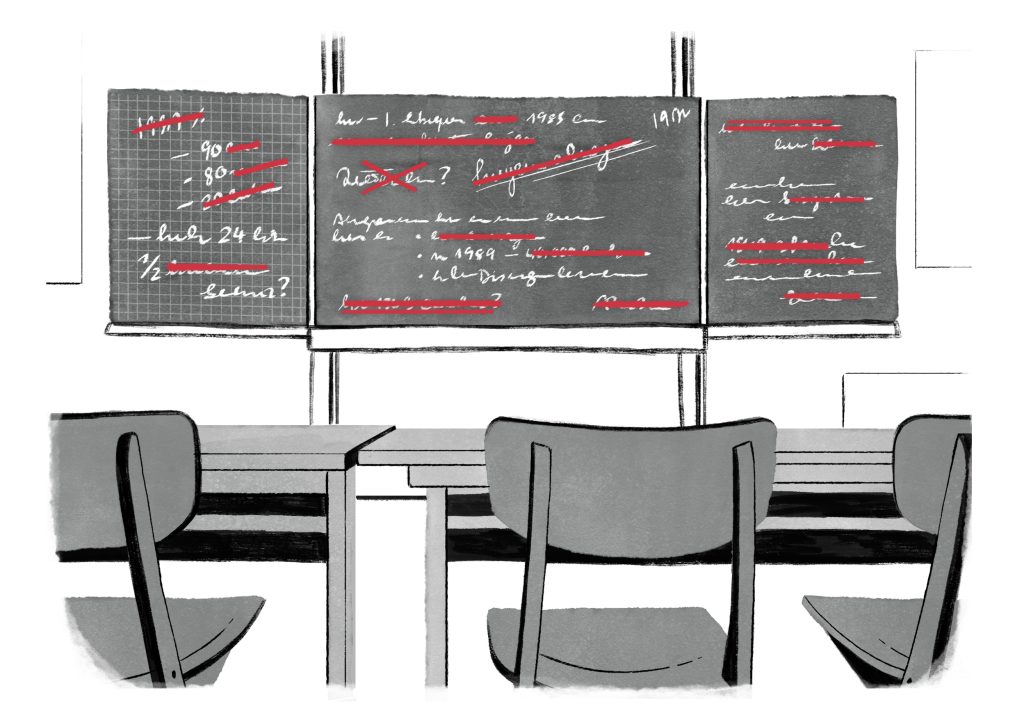

In recent weeks, Sergei Kravtsov, the Russian Minister of Education, announced the release of an updated Russian history textbook for teaching Russian students in the 10th and 11th grades. As of September 1, students will be educated as per the Kremlin’s interpretation of history since 1945 in response to the “information war” and “physical” war facing Russia today. The new curriculum now introduces what Kravtsov termed “the most important events,” including the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol, the causes and course of the “Special Military Operation,” the integration of “new regions” – Luhansk, Donetsk, and Kherson – into the Russian Federation.

The textbook is the latest manifestation of the return of ideological education in Russia, where mandatory instruction in schools and universities must align with the Kremlin’s interpretation of politics and history. The course syllabus for “The Fundamentals of Russian Statehood,” which will soon become a graduation requirement for all Russian university students, comprises five segments covering areas such as “What is Russia?” “The Russian civilisation-state,” “Russian Worldview and the Values of the Russian Civilization”, “Russia’s Political Order,” and “Future Challenges and the Country’s Development.” A consistent theme throughout the curriculum guidelines is patriotism and the need to instil a “mature sense of citizenship.” The youngest generation of Russians is also not exempt from this move towards patriotic education. Since September 2022, children as young as six have had “Conversations about Important Things,” an extracurricular course emphasising heroism, love of the Motherland and national unity.

The objective of these educational programs is, to use the terminology included in The Fundamentals of Russian Statehood, to close the gap between the “psycho-behavioural particularities of the younger generation” and “the realities of higher education” as failure to do so “may result in political instability, the escalation of social tensions, and the aggravation of existing schisms within society (generational, for example).” These courses incorporate what has been termed a civilisational approach to history, where Russia continues its ascent towards greatness as a “guardian of the world’s equilibrium” through its single and continuous thousand-year history. In contrast, the West is in a state of terminal decline. To undermine this position, the West has become “obsessed with destabilising the situation inside Russia” by drawing it “into a series of conflicts and ’colour revolutions,’ to destabilise its economy and replace its authorities with puppets.” Instructors will teach students the Kremlin-endorsed and constructed interpretation of recent history: portraying the 2014 annexation of Crimea as a move to secure peace, labelling Ukraine as an artificial state with a neo-Nazi government, and asserting that Russia initiated its Special Military Operation for the “pre-emptive provision of Russian security.”

Presidential Aide Vladimir Medinsky, one of the chief architects, boasted in announcing the release of the textbook that they had completely revised the period spanning the 1970s to the 2000s according to the state’s point of view. The authors received additional praise for completing their task so quickly: just under five months, with a further supplement planned following Russia’s hotly anticipated victory in Ukraine.

By creating an educational framework where the state dictates facts over independent and impartial experts, the Kremlin ensures that history will be utilised to reinforce its long-term policy goals and to act as a shield against potential criticism for the foreseeable future. In reshaping the next generation of Russians into a “patriotic intelligentsia,” the Kremlin is investing in indoctrination to provide an intellectual basis for what constitutes Putinism and, in doing so, undercut opportunities for dissent amongst younger Russians. Students are encouraged to revel in the historical triumphs of the Russian nation and the injustices it has suffered to ensure their readiness to defend its legacy. The Kremlin’s comprehensive strategic narrative informs some impactful policies and provides credible justification for their execution.

While historical narratives inform its development, a strategic narrative is a means for political actors to construct a shared meaning of the past, present, and future to shape the behaviour of domestic and international actors. By appealing to commonly held beliefs and experiences, narratives are more than mere rhetorical devices, as they can resonate with collective identity. These, in turn, also provide important leverage in legitimising the state’s power structures and political practices, as the state discursively constructs credible narratives about issues, identities, and enemies, both real and imagined. The imaginable lasting impacts of this education campaign should not be underestimated, as this revisionism may normalise perpetual conflict against external forces as state policy and legitimise crimes committed in the name of the Russian nation. In such a conflict, the truth is the first victim, but it surely will not be the last.

Angela-Gabrielle Palmer is a Hertie School of Governance alumnus (EMPA 2017), currently undertaking Doctoral studies at the University of Sydney. Born in Hobart, Australia, she holds degrees from the University of Tasmania and University of Melbourne, where she studied Political Science. Angela was Section Editor for The Governance Post’s Digisation and Technology Section, working in the role between 2016-2017.