Covid-19 has indiscriminately shed light on the most vulnerable, undervalued, and underpaid of our society: migrant women working in the care sector. A new regime of inequality is observed at home, one between women – a regime that has been fueled by the failure of mono-dimensional policies to address gender equality across Europe.

When the World Health Organization (WHO) announced in March that the status of the coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak had transitioned from an epidemic to a pandemic, many asserted the idea that the virus doesn’t discriminate. Indeed, Covid-19 targets all individuals, irrespective of age, race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, and ability. But the truth is, discrimination does come into play. Our ability to defend ourselves from contracting the virus is inextricably linked to our race, class, and gender. Covid-19 puts the lives of those on the fringes of society most at risk. One of the starkest examples of this vulnerability can be found in a minority that lies at the intersection of these facets: undocumented migrant women working in the care sector.

As the pandemic warrants individuals to #StayAtHome, the hardships of these underpaid and undocumented women are made explicit. Vulnerable to unemployment because of precarious zero-hour contracts, these women do not get tested in fear of deportation, and without access to healthcare, put their lives – and the lives of others – at risk.

Employment in the care sector refers to performing reproductive and residential work, including the cleaning, cooking, and caring for others. Whether it is the “invisible labour” performed by women at home or nursing done in care facilities, these tasks are feminised and devalued. Along with gender, a hierarchisation between workers is enforced based on immigration status, ethnicity, and race.

Gender equality projects and policies over the last few decades such as “Girls’ Day” and paid parental leave have enabled more women to break into fields they were previously excluded from. However, as a consequence, these women no longer have the time to perform the invisible labour they did in the past. One in seven care workers in the UK come from outside the EU, and about 73.4% (or around 8.5 million) of all migrant domestic workers worldwide are women. Moreover, the high costs of formal care work by qualified workers lead to a stratification of the labour market for this sector. Insufficient state support for formal care and uncontrolled cash-for-care transactions have led many private households to turn to live-in or daytime employment of migrant caregivers.

For example, in Germany, three and a half people would be required to perform the work entailed by 24-hour care at a cost of over €10,000 per month if their social and labour rights were respected. The German care system “tacitly depends on informal work of migrants”; like many other States, the government turned a blind eye to undocumented migrant caregivers who offer cheap and flexible care, while sweeping the reality of undocumented work under the rug. To cut corners, these tasks are outsourced and monetised to migrant and often undocumented women. These include healthcare professionals whose accreditation may not be recognised in Europe, while others may be in Europe by overstaying a short-term visa in search of higher income, or were born to undocumented parents themselves. No matter their origin, these migrants are vulnerable to employer intimidation and exploitation. Unlike their employers, they do not have access to national labour or social rights such as healthcare and unemployment benefits.

“The government turned a blind eye to undocumented migrant caregivers who offer cheap and flexible care, while sweeping the reality of undocumented work under the rug.”

Personal accounts have also shown how workers without legal status do not want to draw attention to themselves by asking for such rights. In the words of Boris from Torun, “you just work where they pay you the best.”

The deep-rooted gendering of work feminises and devalues domestic labour, and the high costs for formal care work in Europe incentivise private households to resort to informal solutions. Gender segregation and female devaluation implies that despite doing the same work, migrant women earn less than nationals would for a job already deemed low-skilled. Due to this devaluation, migrant women are often restricted from applying for formal job visas because their salaries do not meet the minimum threshold, which in the case of the UK is £20,480. These limitations illustrate how “high-skilled” and “highly paid” are de facto interchangeable. Jobs considered “high-skilled” are associated with high pay, yet migrant women care workers at the buttress of the economy are considered low-skilled and often receive a salary below the threshold. These othering and gendering effects impose a double disadvantage experienced by migrant care workers.

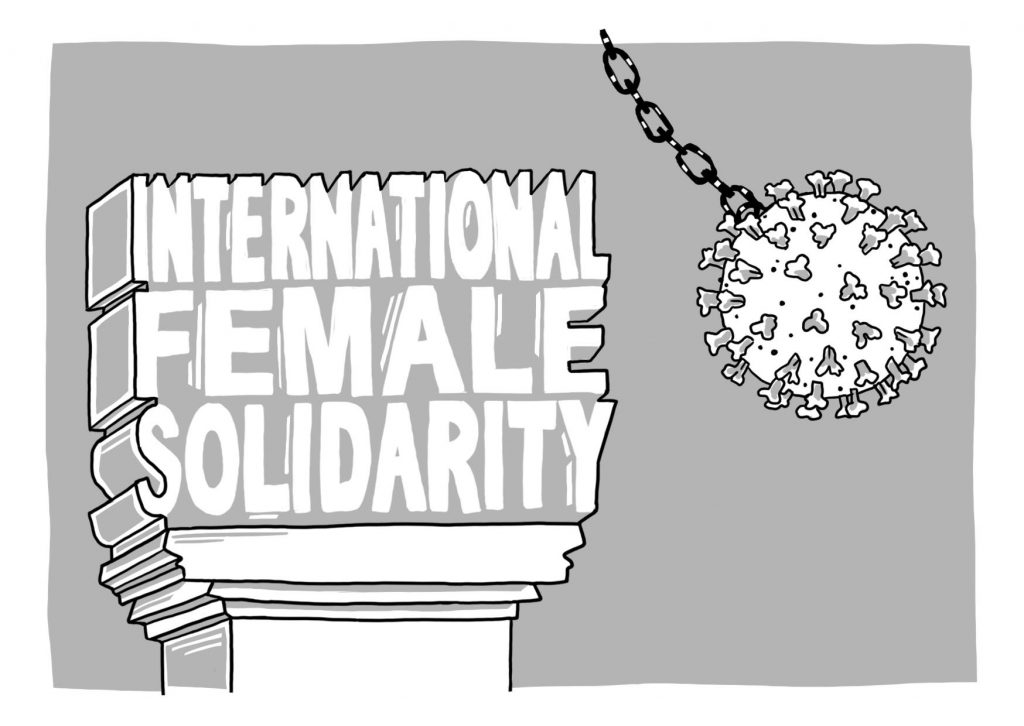

The truth is that the home has become a battleground for a new regime of inequality, one between women. Instead of improving gender equality, patriarchal structures are reinforced, leaving male privilege unchallenged. The single-axis framework of gender equality policies has only emancipated the supposed highest pedigree of women, leaving migrant women behind. By both passively and actively enforcing this power dynamic, a cleavage in transnational sisterhood is created. The outbreak of Covid-19 worsens these circumstances for migrant care workers because it exemplifies how these women are at the mercy of private employers and, in many cases, still work and risk contracting the virus without a system to rely on.

“The single-axis framework of gender equality policies has only emancipated the supposed highest pedigree of women, leaving migrant women behind.”

Although undervalued, underpaid, and for the most part invisible, women’s care work, including that of migrant women, lies at the heart of a functioning economy. Migrant women support an understaffed care system, with their own rights to health and well-being eroded, and their healthcare needs unfulfilled. Because we do not acknowledge that this invisible labour counts as productive labour, white women make career advancements and use that income to enforce hierarchies in a “bond of exploitation”. Contextualising the status of these undocumented care workers reminds us that the labour market is rooted in hierarchal gender structures. At the same time, it underlines how the economic and social implications of the pandemic are especially challenging for these women.

Without undermining the challenges experienced by migrants from a spectrum of professions, legal statuses, sex, abilities, orientations, races, and ethnicities, the rights of migrant care workers call for their own light. Excluding the potential for material relief to those who need it most in our policy approach is the same as leaving them to fight for themselves. Policymakers must employ an intersectional approach to guarantee that no minority, of any combination, including the gender spectrum, gets left behind. Policies that prioritise migration enforcement over health and human rights damage migrant women’s health and are incompatible with the empowerment and equality of women. Instead, social and economic protection for migrant women should be assessed holistically – from a migration, health, gender, and family perspective. Only by addressing the systemic inequalities faced by one of the most disadvantaged can we work towards ensuring that all others are protected. Otherwise, we risk advancing the rights of some while leaving others behind.

Those who are structurally discriminated against face the most volatile problems, and it is crucial that we acknowledge the system that has subjugated the women who lie at the bedrock of our societies. Amidst the myriad of other challenges posed by the outbreak, Covid-19 provokes us to rethink the way we find value in labour. The racialisation and feminisation of care work limit the prosperity of migrant care workers, and in fear of deportation, or by consequence of austere immigration laws, restricts them from getting the help they need. Taking an intersectional policy approach by combatting social exclusion, improving the rights of non-citizens and access to education, employment, social protection, health services, and asylum helps us reduce barriers to labour market participation.

Gender equality policies have emancipated some women at the expense of others. Instead of wholeheartedly combatting the patriarchy, these policies have further segregated the hierarchical labour market based on gender, class, and race. The coronavirus outbreak sheds light on the vulnerability that our most marginalised face at a systemic level: without labour rights, the status of migrant women working paycheck to paycheck is more volatile than ever. Without expanding immigration and social rights, migrant female care workers – who are fundamental to our societies – will continue to be one step behind everyone else.

Paxia Ksatryo is a 2021 Master of Public Policy candidate at the Hertie School and holds work experience in communications both in the private and public sector. Raised in Seoul, South Korea and Jakarta, Indonesia, she completed her BA in Social Sciences at Sciences Po Paris with a regional focus on Europe and Asia. She is interested in understanding power dynamics, systemic inequalities, and digital governance. In her spare time she enjoys writing off-beat Google reviews, italodisco, and reading architecture magazines.