This is the second part of a three-part series about India’s Citizenship Amendment Act. In this article, we talk about the rise of student protests in response to the Act.

More than ninety days have passed since the Indian government passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) on December 12, 2019, which sparked widespread protests against the Act across the country. The largely student-led protests were centred around public-funded universities. While the momentum of the demonstrations stayed constant, it is important to note that pro-CAA demonstrations came as a response to the anti-CAA. Both sides have taken to the streets with slogans and registered marches. There is, however, a point of distinction between the subsequent action of the State and the police, which has seen them show a bias against the anti-CAA side.

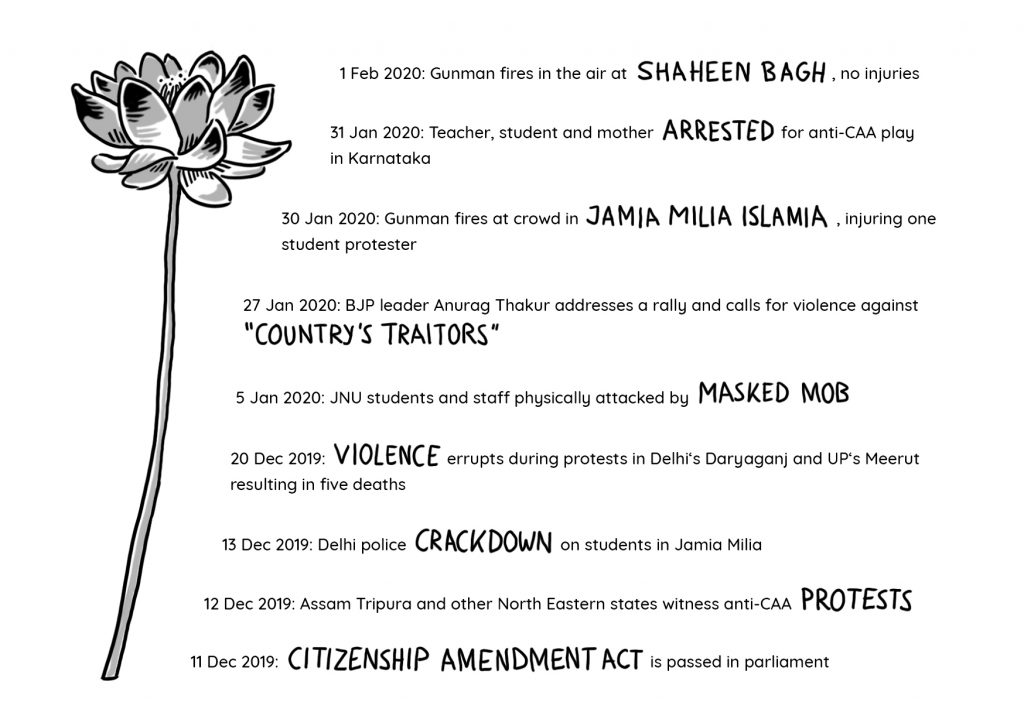

This is a stream of information to forward an accurate timeline of events that led to the large-scale protests. Social media and biased reporting were instrumental in painting anti-CAA protestors as ‘violent’ and ‘dangerous’. While violence did break out in the protests, we take a look at the events that led up to it.

The initial protests began in Assam, where people took to the streets in large numbers to object to the CAA and NRC (National Registry of Citizens). The student-led agitation was subjected to police firing and a State-imposed internet shutdown. Clashes between the protestors and the police led to five deaths.

On December 13, students from Jamia Milia University in New Delhi faced heavy police clampdown, after they organised a peaceful protest march against CAA from the campus to the Parliament, where they were blocked by the Delhi Police. The protest turned violent after stones were pelted. Details of the instigators remain vague. The Delhi Police cracked down on the protestors by using tear gas shells and hit students with batons.

Students and faculty of the Aligarh Muslim University, in Uttar Pradesh, which borders the capital Delhi, subsequently rose in protest against the use of violence on the students in Jamia. The UP government responded by imposing Section 144, a colonial-era law of the Indian Constitution, which legally prohibits gatherings of more than four people.

The blatant use of violence and law to curtail voices of dissent by the Narendra Modi government has been regarded as undemocratic. Mainstream media opinion on these protests was biased, with most TV news channels airing the protests and protestors to be instigators of violence. Media has pinned incidents of stone-pelting, the use of batons, and the burning of vehicles on students. This narrative around the nature of intention of the student protests was instrumental in the clashes that later broke out between pro- and anti-CAA protestors. This begs a further question on the redundancy of the pro-CAA group: what need is there to protest for a law that has already been passed?

Indian students studying abroad were also crucial in registering their protest. The diaspora has voiced their fury against the CAA and the Modi government’s handling of protests from various cities across the US, Germany, and the UK. Hoards of people marched in front of the Indian Embassies in these places. However, students overseas had the privilege of organising freely without coming under attack by the government or the police. In stark contrast, a German exchange student in Chennai was deported back to Germany for participating in an anti-CAA protest.

The setting of the public Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi became a critical turning point for the string of student demonstrations in India. On the evening of January 5, a masked mob entered the campus carrying sticks, stones and metal rods and attacked the students and staff of the university. These students had been protesting against a fee hike, which led to a scuffle between the left-wing student group and the administration. This has been said to be the cause of the terror that was unleashed on the campus. Students were attacked by the masked mob in their hostels, and 26 people were injured. Amidst the panic, the Delhi police were informed, but they did not intervene and remained outside the campus till nine o’clock at night. It was later confirmed by their own admission that the masked mob consisted of members from a right-wing student group called Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parsishad (ABVP).

The inaction of the Delhi Police, who in explaining its failure to take quick action against the perpetrators were unable to make any arrests in the matter – even with sufficient proof – plays hugely into this story of violence and unrest. The Delhi Police has come under immense public scrutiny for its role in the protests, accused of furthering the government’s agenda on the citizenship law. Protection is guaranteed to those who agree with the government, while sedition cases are filed against student leaders who do not.

Police brutality and violence during protests were largely reported from states that are governed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). With the use of force, thousands of protestors have been detained by the police and at least 25 people have died since December. Most of these deaths were reported from Uttar Pradesh, where the police fired bullets on the protestors.

The aftermath of JNU saw protest marches erupting in many cities – Bangalore, Mumbai, Guwahati, Kanpur and many more. Uttar Pradesh, the largest state in India, was put under Section 144 in the wake of the protests across the state. Not just UP, this law was used by the government in other cities as well – Bangalore, Tripura, Shillong to name a few – to curb the growing movements of the anti-CAA protests.

Muzaffarnagar in Uttar Pradesh has found itself at the centre of this brutality. Eyewitness accounts state that the police barged into houses at midnight, perpetrated violence, and vandalised property. In the aftermath of a peaceful protest, the Uttar Pradesh Police rampaged the town and destroyed personal and public property, including CCTV cameras. The Muslim community in the area was clearly targeted as they bore most of the damage.

The situation in New Delhi worsened at a time when its citizens were called upon to go to the polls for the State Elections.

An area called Shaheen Bagh became the focus of the nation. On December 15, housewives from the Muslim majority region decided to orchestrate a sit-in in an indefinite protest against the CAA-NRC. This women-led move of defiance took place during the harshest winter that Delhi has witnessed in the last 100 years. They have been protesting for more than two months and have inspired other women to organise and protest together.

Patna and Gaya in Bihar, Prayagraj and Kanpur in UP, Pune in Maharashtra, Kolkata in West Bengal, Khureji Khas in Delhi, and Chennai in Tamil Nadu. These are all indefinite women-led sit-ins that are agitating against the discriminatory bill, each of them waiting for the Modi government to address their grievances and repeal this law. What ensued was an election campaign filled with hatred and anger. The Shaheen Bagh rise-up became a hotly debated election issue, with BJP leaders openly calling for violence against everyone who stood by the idea of it.

Pro-CAA demonstrations were a major boost to BJP’s propaganda, especially in Delhi. Protests were held in various regions across India, such as in Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Maharashtra. The nature of the violence stemmed from hatred against targeted communities, such as Muslims Shaheen Bagh. At a pro-CAA rally on January 27, BJP leader Anurag Thakur, in an explicit declaration of violence, said, “Desh ke gaddaro ko, goli maaron saalon ko” (Shoot the people who betray their country). An open threat clearly directed at the women of Shaheen Bagh.

The nature of violence until this point had been restricted to stone-pelting and the use of batons. However, on January 30, it escalated to include guns. A man brandishing a firearm at an anti-CAA rally opened fire and injured a protester. Images of the assailant brandishing his weapon at protesters while the police were standing idle some distance behind him went viral. He was later arrested by the Delhi Police. A second shooting took place on February 1, where a man shot into the sky. No one was hurt. Eyewitnesses say that he shouted, “Hindu Rashtra Zindabad!” (Long live the Hindu-country!).

Amidst the hundreds of protests that emerged across the country, the Indian media chose to highlight two: Jamia and Shaheen Bagh. It framed these protests as though it were only Muslims who were protesting. While the issue of the CAA-NRC does affect Muslims the most, to give the protests a religious angle is a propagandist move. Ever since the BJP came to power in 2016, India has witnessed many incidents of religious polarisation – from promises of a Hindu Rashtra (Land of the Hindus) to carrying out lynchings. A citizen’s right to dissent has also been curbed in the current political landscape, with any dissenter branded an ‘anti-national’.

The media narrative has tarnished the JNU as a breeding ground for the “tukde-tukde gang” (left-liberals). This idea of the “tukde-tukde gang” was propagated by BJP leaders about leftists – be they JNU students, journalists, or academics – who they say are trying to divide the country by questioning the government.

This systematic use of language to address people with a different political ideology and the media giving in to this narrative of hate have led us to a point out where dissenting students are seen as a threat to the public. Where a peaceful protest by housewives fighting for their rights as citizens of a country is falsely portrayed as their radicalization. Where the mainstream media – the fourth pillar of democracy – is now just an extension of government propaganda.

Ayushka Anjiv is a first year MIA student from India with a research interest in human rights and migration.

Abhipsha is a first-year policy student with an interest in food security and development. Her waltz through different career paths has finally led her to what she wants to do, or that’s what she thinks.