Indigenous communities around the world are living on the frontlines of the climate crisis. As the changing climate threatens the wellbeing of their communities, Indigenous activists are calling for the renewal of nation-to-nation relations and a paradigm shift in policy making towards Indigenous self-determination. Can the establishment of a harmonious relationship amongst Indigenous and non-Indigenous governing bodies, informed by traditional ecological knowledge, ensure a viable planet for generations to come?

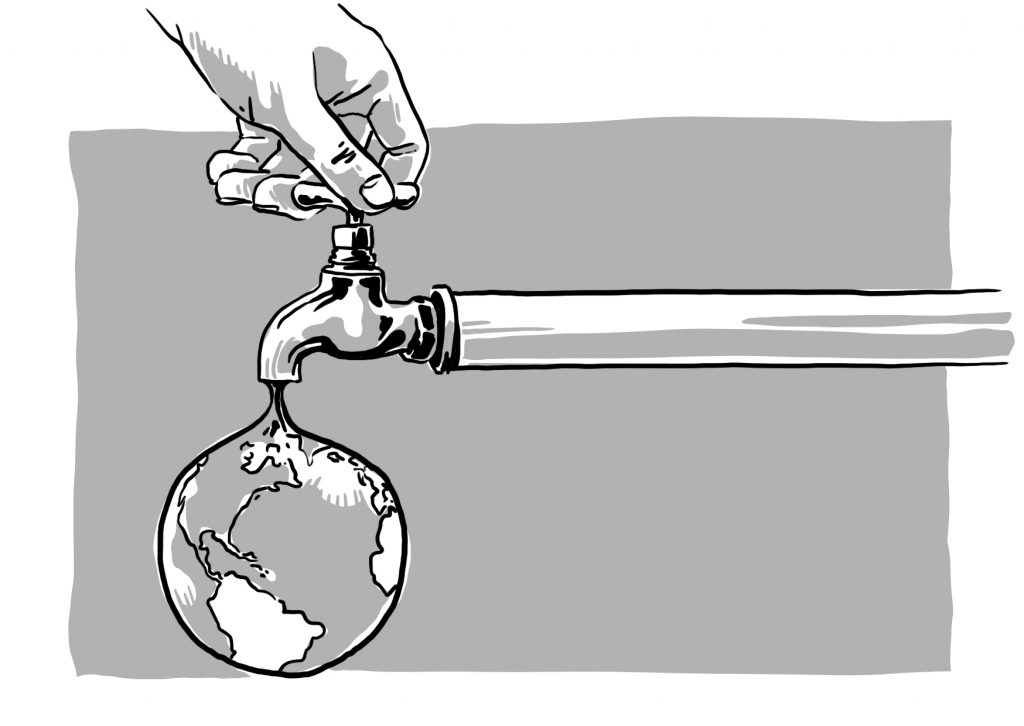

Autumn Peltier first learned about the importance of water from her great aunt, Josephine Mandamin. As the founder of Mother Earth Water Walk, Josephine walked the nearly 17,000 kilometres of the shoreline of the Great Lakes to raise awareness for water conservation on Indigenous land. Given her upbringing on the largest freshwater island in the world, Autumn continues to honour her aunt’s activist history through her connection to water. However, as a young member of Wiikwemkoong First Nation and resident of Manitoulin Island, Autumn has had to bear witness to the unfortunate reality of drinking water advisories for Indigenous peoples across Canada. This reality has plagued First Nations communities for decades as short-term and long-term drinking water advisories continue to be called by federal infrastructural advisors due to the ongoing effects of climate change, infrastructural mismanagement and natural resource extraction. Presently, at the young age of fifteen, Autumn serves as Chief Water Commissioner for the Anishinabek Nation which is a political organization made up of 40 First Nations across Ontario. Following in the footsteps of her great aunt, Autumn was chosen for this role by members and leaders within the Anishinabek Nation and she continues to learn about the importance of water from a cultural, spiritual and ecological perspective.

“Now is the time to warrior up and empower each other to stand for our planet. We need to sustain the little we have now and develop ways not to pollute the environment and sustain the relationship with Mother Earth and save what we have left,” she powerfully delivered at the United Nations General Assembly. Informed by the traditional learnings from her Elders, Autumn has used her platform to openly criticize Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Canadian federal government for their “broken promises” in addressing the ongoing water crisis on Indigenous land. In her young life, Autumn has established herself as a prominent voice for change in an arena where her urgency is matched by the efforts of Indigenous climate activists like Quanna Chasinghorse and Helena Gualinga who have advocated for the protection of Indigenous land in the United States and South America respectively. However, their narrative is not novel – their pleas for change are bred from the past of their people that have been subjected to assimilatory and discriminatory policies for centuries.

From a policy perspective, any attempt to rectify the discourse between Indigenous peoples and the state will have to acknowledge the troubling history of colonial practices that have created a deep mistrust of the policy process. To advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and address the impacts of climate change, policy makers and non-Indigenous peoples will have to reflect on the violent and discriminatory actions of the past and dismantle the institutional and cultural inequities that serve as barriers to Indigenous self-determination. Given the omnipresent climate crisis, policymakers are in a position to rebuild nation-to-nation relations with Indigenous peoples – in addition to addressing the effects of climate change – by reframing the policy approach taken to natural resource management. Globally, models of multi-level governance over sacred Indigenous land and water have emerged in Canada and Australia and can be used as examples to inform policymakers in states with prominent Indigenous populations of the approach that can be taken to mitigate the ongoing climate crisis and the renewal of national resource management policies.

Climate change disproportionately affects Indigenous and marginalized populations; the pervasive role of colonialism in capitalism has enabled the desecration of sacred natural resources and has resulted in the degradation of the health, safety, and freedom of Indigenous people. The global conversation on climate change implicates human rights as it will shift migratory patterns and accelerate economic disruptions for the populations of people most vulnerable to it. As such, strides have been made to address global Indigenous inequities through the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2006. The declaration is structured to facilitate Indigenous self-determination and outlines formative policy principles that enable the “survival, dignity and well-being of Indigenous peoples”. However, in many political contexts, little progress, due to a lack of political will as well as institutional and infrastructural support, has been made on advancing the UNDRIP’s objectives.

Naturally, the policy response needed to address the impacts of climate change will have to encompass the infrastructural, economic and cultural implications of a warming planet. Echoing the sentiments seen in the UNDRIP, a “visible Indigenous interest” can be easily integrated within the policy process addressing climate change and natural resource management because it enables the use of Indigenous ecological knowledge when designing sustainable resource management practices. From a theoretical perspective, multi-level governance has been lauded as a conceptual tool for advancing Indigenous-settler relations because it is a “policy process that engages a variety of actors located at different territorial scales, the outcomes of which are the product of negotiation rather than traditional hierarchical orders such as delegation.” It is clear that a multi-level governance approach to climate change enables the development of a holistic perspective on the treatment of natural resources as opposed to the colonial tradition of resource exploitation and allows for “participatory conservation planning and resource co-management regimes”.

Successful examples of multi-level governance models have been found in Canada and Australia and demonstrate the importance of enabling Indigenous self-determination in the policymaking context.

The emerging policy practice of collaborative consent enables the integration of reconciliatory principles in natural resource management. In the case of Canada’s Northwest Territories, the introduction of the Devolution Agreement enabled the negotiation of the transfer of jurisdictional power from the federal government to the Government of the Northwest Territories and Indigenous governments. Through the use of monitoring protocols that implement traditional ecological knowledge and bilateral water agreements, this agreement bestowed the responsibility on the Government of the Northwest Territories to oversee public land, collect resource royalties and ensure the management of natural resources is conducted in accordance with settlement agreements. In addition, the Northwest Territories Water Stewardship Strategy (NWTWSS) is an example of situating natural resource management as a shared responsibility between regional resource boards and Indigenous governments.

In Australia, natural resource management has emerged as a prominent avenue for Indigenous people to regain control over the planning and oversight of their terrestrial and marine-based custodial lands. The use of consensus-building has enabled Indigenous peoples to integrate traditional Indigenous knowledge into sustainable resource management practices and bestow the control of decision making to Indigenous leaders via cooperative agreements with local governments. Australia’s “Working on Country” program in the Northern Territory supports an equal partnership approach to natural resource management and operates using a “collaborative management” model where many stakeholders and bodies of knowledge inform policymaking regarding sacred natural resources. The program has hired nearly 700 Indigenous rangers through a labour model that addresses Indigenous poverty rates and natural resource management by enabling conservation efforts for nearly 1.5 million square kilometres of Australia’s Northern territory.

As demonstrated by the case studies in Canada and Australia, reconciliatory efforts within the global context must incorporate policy frameworks of rights-building where Indigenous peoples are recognized as self-determining governing bodies responsible for the health of their communities and land; the feasibility and viability of the cases presented earlier are contextualized within the institutional landscape that defines the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the state. Therefore, when applying the model of multi-level governance and collaborative management models in contexts outside of the Commonwealth, policy leaders should look to the UNDRIP to ensure the establishment of equitable nation-to-nation relations. Through the development of bilateral agreements, the incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge in resource management methodologies and substantial infrastructural support, Indigenous people can assert their rights as decision-makers rather than stakeholders over the lands they inhabit. By operating under the lens of self-determination of Indigenous peoples, the sustainable management of sacred resources such as land, water, and air can ensure a future for our planet that Autumn Peltier and the coming generation of changemakers can be proud of.

Lamia Aganagic is a settler on Indigenous land from Toronto, Canada, and a Master of Public Policy candidate from the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. Prior to her graduate candidacy, Lamia conducted her Bachelor of Kinesiology with High Honours at the University of Toronto, which uniquely positions her primary policy interest at the intersection of urban and social policy. Within a keen understanding of the impact policy making can have on the health and social outcomes of marginalized populations, Lamia is passionate about seeking equitable solutions, adopting inclusive frameworks, and analyzing public policy using an intersectional lens.