Despite a mild winter, the heated discussions at this year’s Munich Security Conference over a return of Cold War-like disputes ensure that Russian gas supply will remain on the agenda. During the recent years, Moscow has given the EU’s Central and Eastern Member States viable reasons to fear that Russia will cling to its only remaining leverage by using gas as a political tool. This sentiment should be taken seriously by the entire Union, but it appears to be deliberately overlooked, especially in regard to the Nord Stream II gas pipeline extension.

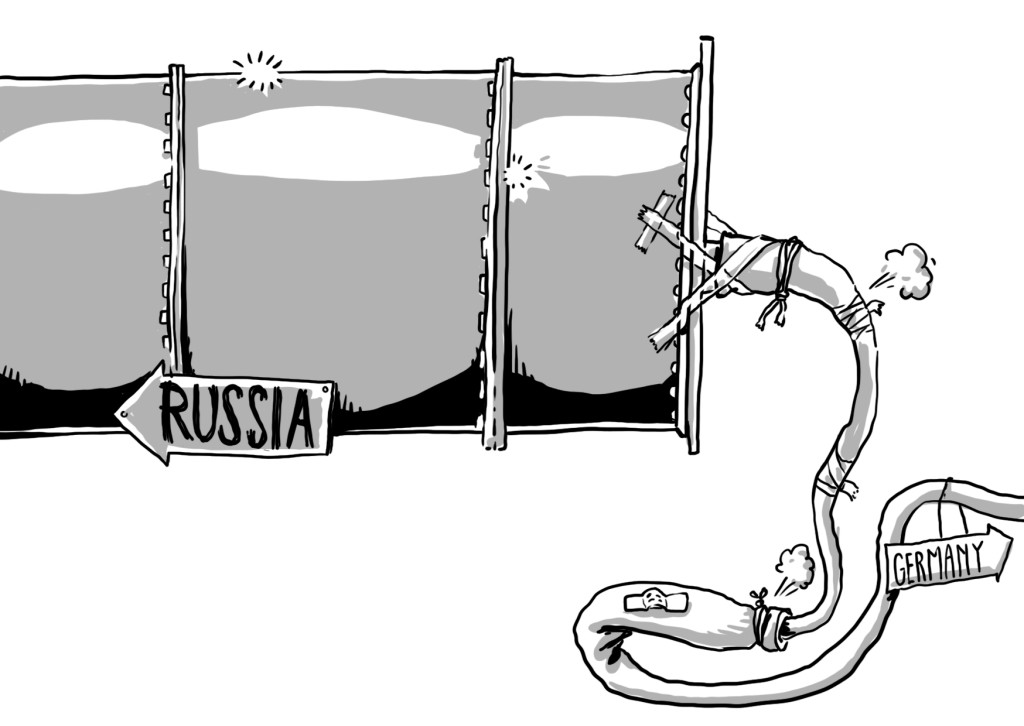

Running through the Baltic Sea since its completion in 2011, Nord Stream brings Russian gas to Germany, thereby avoiding direct gas transfers and, by extension, transit fees to Poland. With the planned doubling of its current capacity, 80% of European gas imports from Russia would run via the Baltic Sea.

The German government and the Commission should rapidly put this geopolitically and economically sensitive project to a halt before it causes further fracturing of relations with the significantly-affected EU Member States of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and places Ukraine’s economic security in jeopardy.

Undermining European solidarity and credibility

Firstly, Nord Stream II would ruin the EU’s goal of diversification of gas supply. Although a reduced dependency on Russian gas remains the main idea of the EU’s Energy Union and the European Strategy for Energy Security, the Commissioner for Energy Maros Sefcovic has sent mixed messages regarding his approval of Nord Stream II. While in November, Sefcovic raised doubts over the project as a whole, an interview with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in February revealed that he might leave it to the parties involved to decide upon the realization of the project.

Secondly, the political implications of Nord Stream II need to be viewed critically. Advocates of going back to ‘business as usual’ tend to forget the role geopolitics is assuming once more. Since the annexation of Crimea, it seems apparent that Russia does not abide by the same rules as other players. The Kremlin still relies on hard power by using underhand hybrid warfare methods and threats to cut off gas supply.

Thirdly, is it true that Russia remains too dependent on the EU’s demand for gas to interrupt its supply? This claim only holds if Nord Stream can be prevented. Seen as a whole, Russia and the EU are indeed interdependent. Due to the Ruble’s devaluation and gas prices being pegged to oil prices by a half-year to nine-month delay, demand in the EU for lower-priced Russian gas will remain high. Gazprom will therefore stay highly interested in appearing as a reliable supplier. If, however, the European gas market is split via Nord Stream II, Central and Eastern Europe will have reason to fear Russia’s increased leverage in using gas as a political weapon.

Ignoring the Central and Eastern Member States’ Interests

Russia’s gas cut-offs towards Ukraine in 2006 and 2009 and the resurging disputes last year rightfully stick in the memories of CEE members. The former socialist states remain much more dependent on Moscow’s gas supply than other Member States, as illustrated above. Yet, the Russian focus on gas trade to Europe lies in the continent’s West, which demands three times as much Russian gas as the aforementioned former Soviet states.

Financial repercussions of Nord Stream II for CEE would be detrimental. Poland would lose the transit fees it currently still receives by transporting gas through the Yamal-Europe pipeline to Germany. The Czech Republic would need to fear higher prices if all Russian gas would be imported via the extension of Nord Stream, the new Gazelle pipeline. Nord Stream II would also exclude Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Belarus and Slovakia from gas transits.

If the EU wants to prevent Ukraine’s financial collapse, it must ensure that gas flows from Russia via Ukrainian pipelines beyond 2020. Ukraine currently gains 2 billion Euro, equal to 6 percent of its budget, from gas transit. Nord Stream II would add additional pressure for reform, but it will take years until Ukraine and all Member States of the CEE can become less prone to Russian gas cut-offs via the Ukrainian pipelines. Despite increased availability of reverse flows, Russia’s ability to pressure Ukraine’s neighbors from providing reverse flows cannot be underestimated. With Hungary or Slovakia being largely dependent on Russian gas, Moscow holds the decisive bargaining chip.

Taking Germany’s perspective, a mere economic point of view might speak in favor of Nord Stream II. Fulfilling the project would enhance Germany’s security of supply, assuming that Ukraine remains unstable and that gas disputes with Gazprom will continue for the next years. Eventually, it would make Germany the number one gas hub and distributor in the EU. However, this position would come at an incalculable political cost.

How Angela Merkel Could Profit From An Alternative

A smarter strategy than ignoring central European Member States’ interests would be to offer a concession on Nord Stream II in exchange for a more supportive position towards Angela Merkel’s course in the refugee crisis. Cooperation in regards to burden sharing on the latter needs to be of higher interest to Berlin than possibly becoming a hub for Russian gas.

Vladimir Putin has not only shaken up the European post-Cold War era for the last two years by questioning Ukraine’s territorial integrity, but also continues destabilizing Syria and thus, adds to the refugee influx to Europe. If the German government rightfully fears the multifaceted attempts by the Kremlin to divide the EU, it should counteract the Kremlin’s strategy and refrain from exacerbating the effects.

Conclusion

Germany and the EU Commission need to be preoccupied with the risk that Nord Stream II would increase the vulnerability of the Member States in CEE and weaken Ukraine. If Nord Stream II is not stopped, the effects will prove hazardous for European unity and facilitate the come-back of Moscow’s influence on its Western neighbors. Exchanging favors with respects to energy security and the refugee question would be mutually beneficial and a sign that with mere soft power, Europe can successfully deal with geopolitical challenges.

Paul Salisch is a first year MPP student at the Hertie School of Governance. During his European Studies BA in Maastricht, he specialized on foreign policy towards Russia and interned with the German Councill on Foreign Relations in Berlin. Since his start at Hertiel he focuses on energy policy.

Paul Salisch is a first year MPP student at the Hertie School of Governance. During his European Studies BA in Maastricht, he specialized on foreign policy towards Russia and interned with the German Councill on Foreign Relations in Berlin. Since his start at Hertiel he focuses on energy policy.

References upon request.