“Disasters amplify the inequalities of the world we live in” , says Mami Mizutori, the United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction.

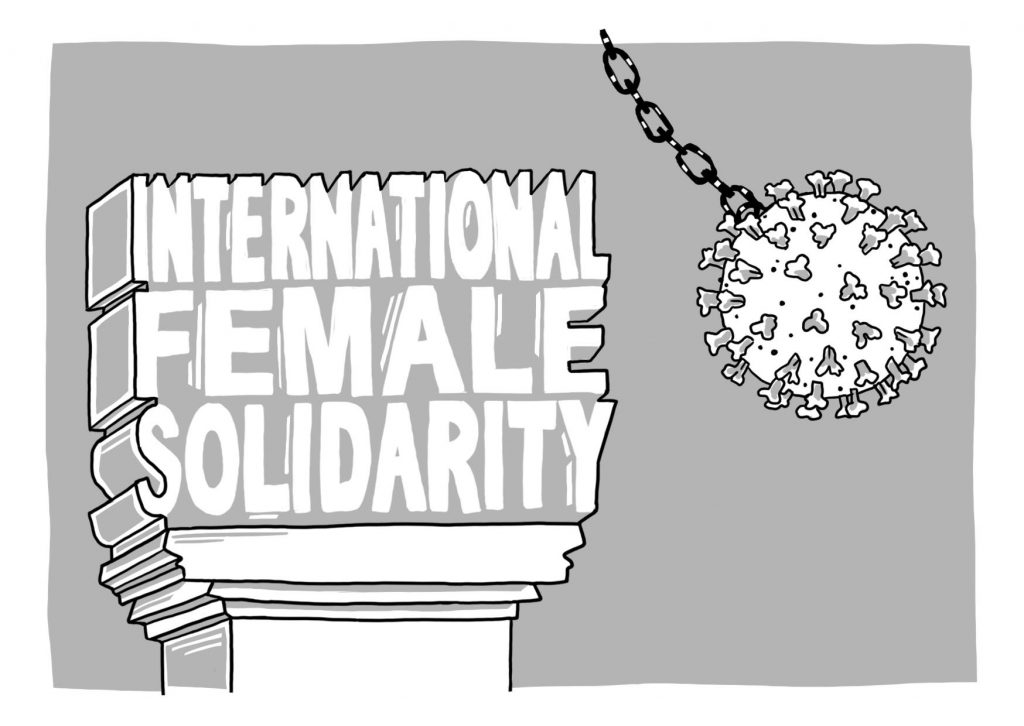

The Covid-19 pandemic has clawed back at decades of progress made with the MDG and SDGs on several grounds. Particularly, the developmental progress on upliftment of minorities and the vulnerable has been eroded significantly by the Pandemic. Or perhaps, as Mizutori states, the crisis has only amplified the inequalities that never were removed.

Leave No One Behind : Urge for an Inclusive Recovery

Sure, a crisis of this scale could not have been predicted and the collateral damage is inevitable. However, with the recovery efforts now in full swing, there is hope and potential to revise narratives, re-align focus and deliver the transformative promise of “leaving no one behind” as we move forward towards a post-pandemic phase.

Women constitute 49.6% of the global population as of 2021, and The International Labour Organisation (ILO) reports that roughly 70% of the frontline workers during the pandemic were women. Despite this number, another ILO report from June 2021 also found that there will be 13 million fewer women in employment in 2021 compared to 2019. The underlying reasons for this decline have been both active and passive as broken down by the January 2022 report by Pew Research Centre. According to the findings of this report (infographic below), the pandemic brunt was borne by unskilled female labour to a large extent , hinting towards active and passive reasons for decline in female labour force. Active reasons encompass reduced female-focussed aid, employment security and livelihood support, while passive reasons include a heavier glass ceiling on women due to disproportionately bearing child-care responsibilities, unpaid domestic labour, and limited childcare. Now, homeschooling of children is also landing as further unpaid care work on women. These factors combined necessitates that some women exit the labour market.

As the global community tiptoes from the pandemic, the need of the hour is a gendered lens on the ongoing and new means of cooperation. Engaging in partnerships through a gendered lens will target both active and passive reasons for the backslide on not just gender equality, but also overarching development.

New and improved means of partnership and cooperation have become commonplace in the recent past and are gaining further traction since the pandemic. This trend is in line with the objective, “Global Partnership” of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals. The scope for gender inclusive pandemic recovery measures is huge, and will be achievable with the leveraging of partnership and cooperation, if only the potential of the instruments of cooperation is unleashed to its fullest.

While the integration of Gender Equality constitutes a standalone goal (Goal 5) and is recognised by eleven of the seventeen SDGs shows that the UN is aware that the SDGs require an integrative approach, this is especially true in the case of Gender equality. Time and again, it has been shown that accelerating gender equality improves several other conditions such as economic growth, poverty levels, food security, climate change, health conditions and accessibility. While building back from the pandemic, fostering the right environment for gender empowerment and higher female economic participation and decision-making can advance an economy towards its SDG targets by leaps and bounds. The crisis can be deemed as an opportunity to revise mechanisms of developmental activities to incorporate higher gender-equal recovery at the outset.

In this pivotal moment, a mere ‘gender’ clause in development projects does not go a long way in ensuring gender equality while recovering from the pandemic. The projects must weave the gender variable to its core. We need the terms of existing development projects to ensure that it caters to active and/or passive causes of unequal recovery from the pandemic. Now is the time to adjust the lens so that not just the pandemic response, but all forms of crisis response can ensure equitable recovery.

Where there is a will, there is a way

The instruments of South South Triangular Cooperation (SSTC) that have been growing in presence since the inception of SDGs offer a promising way ahead. These instruments enable peer-to-peer learning, sharing of technical knowledge and financial resources across the Global North and South. SSTC increases the number of dialogue networks between economies at different points in the development spectrum.This has unlocked diverse experiences and possible solutions to pressing developmental challenges. Ensuring gender equality in pandemic recovery is a shared challenge across most developing economies. Therefore, a coordinated approach by these countries would enhance the quality of results substantially.

The pandemic, as a global crisis, presents an opportunity for employing instruments such as SSTC to set the gender policies right in what looks like the beginning of a new era in development of the Global South. But in order to achieve this, the current model of SSTC that is limited and unsustainable needs to become more inclusive.

SSTC today is still majorly a government led cooperation in Asia. An example is “Global Linkages”, a triangular cooperation project launched in 2016 between US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Indian government to disseminate twenty Indian best practices and innovations in family planning and maternal and child health care to Afghanistan, Nigeria and Bangladesh among other partner countries. Or perhaps the Chinese infrastructure investment in Africa, with centrally operated projects. Or perhaps the IBSA (India-Brazil-South Africa) Fund for poverty and hunger alleviation.

The USAID/India has invested heavily in poverty reduction, health and education for the past 2 decades, yielding several governmental partnerships for innovative and sustainable development across South and SouthEast Asia. But the primary model of this instrument is for the respective government to adopt best practices and scale them to the general population. As a result of convoluted geopolitics and fragile governmental transparency in most of the partner countries, government-to-government models of cooperation are highly unsustainable. USAID recognises that development gaps continue to persist despite its efforts and perceives them as a problem of inclusiveness in the target country. Although this limitation is acknowledged, the programs don’t go much farther in approaching ways to address it. More likely than not, these programs end up counterproductive by accentuating the existing development bias. However, if the developmental programs employ the local/regional partners effectively (and intentionally) in their models, this “problem of inclusiveness” can be bridged and greater rewards can be reaped from the investment.

Similarly, although IBSA covers aspects of disability inclusion, prevention of child marriage and better lives for child marriage survivors in its focus areas of hunger and poverty alleviation, the scope of this fund is quite generic. Especially since the focus areas are ones that particularly affect vulnerable populations,employing a focussed gender lens during project planning, implementation and evaluation could positively revise the narrative of the project, serving as a catalyst to inclusive progress.

Let’s take the case of China, who is a dominant influencer in SSTC trends. In its own development story, China has been highly effective in increasing female participation in government, education and labour force. In fact, the country has one of the highest female labour participation rates in the world, at 62.8%. Despite its impressive internal progress, gender is a widely overlooked phenomenon in the narrative of China’s development. The Chinese developmental models have been adopted for several SSTC activities by China along the BRI and AFRICA as theorised by Chinese economists Justin Yifu Lin and Yuen Yuen Ang. But neither scientist has examined the key role of women in this success story or how this can translate into the model. Given the trends however ,this is not yet a missed opportunity for China.

The good news is that local partnerships are currently booming in the world of international cooperation. A model of triangular cooperation through civil society organisations, that has been in existence in India since the 1950s, has recently resurfaced and is gaining due momentum. With the plethora of CSOs now being involved in Indian development activities, they can be effectively leveraged to drive gender equality inside and outside. The domestic experience of Indian CSOs opens ample scope for sharing knowledge while approaching similar developmental roadblocks in other countries. In the above-mentioned USAID or IBSA models, triangular cooperation networks working in India can connect initiatives and organisations active in the realm of women’s empowerment and gender equality across the partner countries to share their experiences, journeys and resources. A way to approach this can be to involve a gender-focussed CSO in every project area as a mandatory element. There is, however, work to be done to enable a conducive environment so that the CSO model takes off successfully. Once such an environment is created, it will ensure greater levels of transparency, efficiency and trust in project implementation.

Having arrived at the third International Women’s Day since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, we still fall short of making possible an avenue for equal pandemic recovery for women. There is an immediate need for comprehensive measures to escape the vicious circle of bias in development towards the rich and powerful. A feminist recovery plan would not just improve gender inclusivity but will prove to be an overall activatorof growth. Despite a substantial reversal of trends in decades of progress in gender equality due to the pandemic, one must not fail to notice the silver lining – a new scope for retrospection and realignment of scope of SSTCs, which, with a little nudge, can produce the desired outcomes.

Madhumitha is an MIA 2022 student from Chennai, India. She studied commerce and business accounting in her bachelors, but spent most of her time watching anime and learning Japanese. After her bachelors, she worked as a technical agent and later as a document translator in Fujitsu Consulting. She is extroverted, loves cultures , history and social patterns. She briefly interned for the Gender Security project in India where she contributed for the blog and documented gender violence across the world. Her interests lie in the convergence of international trade economics and feminist foreign policy. In her leisure time, she is either outside on a hike, doing yoga or lost in Japanese resources.