In just over two weeks, 88 police officers were injured in riots in Northern Ireland. The unrest constitutes the largest scale of violence in the region since the end of the thirty-year sectarian conflict known as the ‘Troubles’. As tensions reignite, Sinéad Barry analyses what could be the reescalation of the EU’s largest violent conflict.

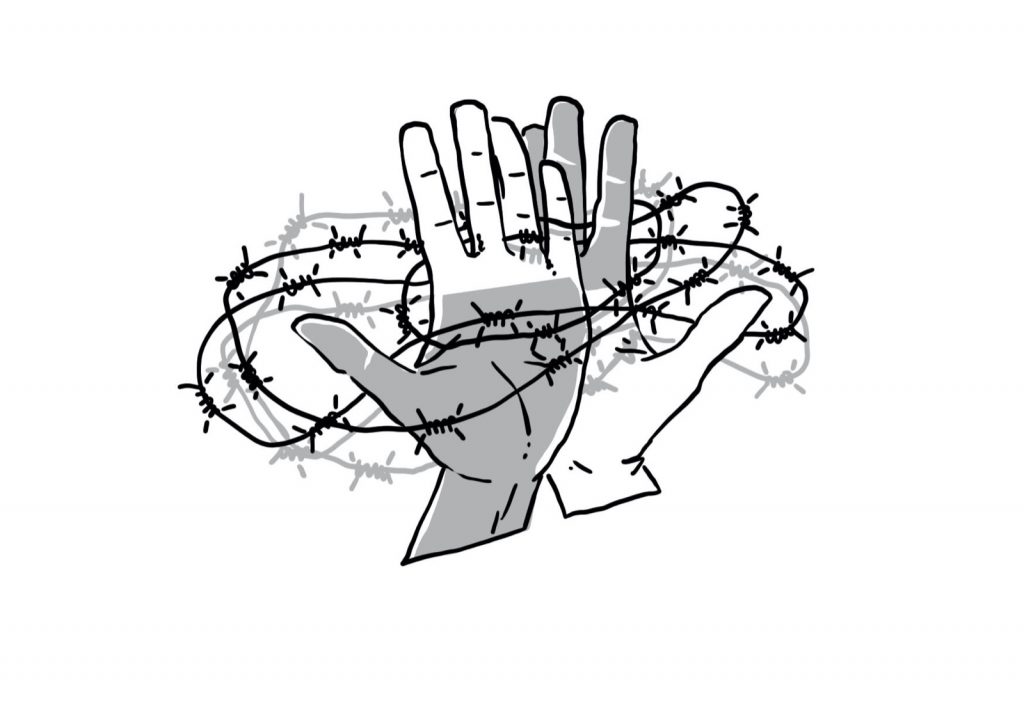

On March 29, 2021, clashes erupted in the city of Derry when a petrol bomb was thrown at a police vehicle. Riots continued for more than two weeks, largely taking place in the state capital, Belfast. Last week, the gates of the so-called “peace wall,” a long partition through the city that divides Catholic and Protestant communities, were pulled open and set alight.

The surge in tension took place around the 23rd anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, the charter that ended the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The clashes were instigated by loyalist paramilitaries, outraged by the sea-border put in place between Northern Ireland and Britain due to Brexit. The riots were met with a violent response from republicans in the region.

The Police Service Northern Ireland (PSNI), however, has not found evidence that the most recent outbreak in violence is linked to organised loyalist groups. Most likely, it has been driven by individuals who may be part of loyalist paramilitaries.

Whose Ireland?

In 1920, during the War of Independence, the island of Ireland was divided, creating the state of Northern Ireland. Its population of one million was mostly Protestant. In general, Protestants in the region are allied with the United Kingdom and want Northern Ireland to remain part of Great Britain. This political principle is known as Unionism, its radical form – Loyalism.

At the time of partition, more than one-third of the population of Northern Ireland was Catholic and nationalist. Nationalism is the support for the reunification of Ireland into one state, and opposition to British presence on the island. Its radical form is called Republicanism, and its legacy is pervaded by the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Before the Troubles began, the state of Northern Ireland was one of total segregation and ubiquitous discrimination against the Catholic minority. Only property and business owners could vote in elections, meaning that the poorer Catholic group was often excluded from voting. Wealthy business owners could accumulate votes, casting an additional vote for every company owned (up to six). Gerrymandering further immobilised Catholic voters, meaning that unionists had unwavering control over political society for more than fifty years.

The Troubles

The Troubles began in the late 1960s but the spark that bolstered it into a fully-fledged sectarian conflict came in 1972 on Bloody Sunday. On this day, 13 unarmed Catholic protestors were shot dead by British paratroopers during a civil rights march organised by nationalists. More were injured, one of whom died some months later due to wounds sustained on that day.

A thirty-year long guerrilla conflict between the two sides ensued. Resulting in more than 3,500 deaths, the Troubles is the most violent conflict to have taken place on EU territory. Republican groups were responsible for approximately 60% of killings during the Troubles, with the remaining caused by loyalist paramilitaries and the British Army.

Although never officially labelled a war, the conflict saw forced disappearances, school bus bombings, and the transformation of thousands of poor adolescents into hardened radicals. The two communities, both Christian, white, and practically indistinguishable from one another to foreigners, occupied utterly different civil worlds in one concentrated space. With the conflict taking place in cities and towns with less than 300,000 inhabitants, its impact haunted every fissure of the small nation. The decades of turmoil propelled a resolute peace campaign, eventually ending The Troubles in 1998 with the Good Friday Agreement. As part of the peace treaty both republican and loyalist paramilitaries disbanded, power sharing between Nationalists and Unionists began, and the British army left the island. The people of Northern Ireland were given the right to decide if they wanted Irish citizenship, British, or both. Aside from several isolated incidents, the region has been stable since then. Northern Ireland remains, however, one of the most disadvantaged areas in the UK and has the lowest level of educational attainment in the EU.

Why is violence reigniting now?

The Good Friday Agreement was written with the presumption of both Irish and British membership in the European Union. Prior to Brexit, it precluded any border issue between Northern Ireland and the Republic. Disrupting this stability, Brexit wreaked political havoc on the region. In Westminster, the Northern Ireland question became an obstacle to the entire Brexit enterprise. Since the onset of negotiations, the issue of how to impose a border that divides the UK from the EU (which still includes the Republic of Ireland) has plagued talks.

Northern Ireland voted against Brexit in 2016 by a 56% majority. This was largely due to the fear of a re-emergence of violence should a border be placed between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Ideological concerns aside, placing a hard border on the island of Ireland would have been logistically unfeasible. Currently, the ‘border’ is invisible. It cuts through towns, rivers, and properties. People cross it every day to go to work and school. Some inhabitants even own farms that sit half in the Republic and half in Northern Ireland.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson promised unionists that there would not be a border in the Irish Sea. Unionists oppose the implementation of a sea border because they believe it divides Northern Ireland from the rest of the United Kingdom and is a step closer to Irish reunification.

As all promises were broken and the sea-border was instated in January 2021, British apathy to Northern Irish unionists was outed. Unionism’s logic began to crack. Defined by their allegiance to the United Kingdom, loyalists stated feeling “betrayed” by Downing Street’s readiness to forget them. Launched into limbo, talks of Irish reunification outraged the unionist community, while talks of a hard border on the island of Ireland incited nationalists.

Another key factor driving the recent reescalation is the Bobby Storey funeral controversy. In June of last year, more than 1,000 people attended the funeral of the senior republican, including several high-level nationalist politicians. Although the decision is under review, the PSNI decided not to prosecute anyone for breaking the lockdown. The move aggravated the growing sense in the Protestant community that the PSNI is biased against them. However, this view is worthy of scrutiny, given that the PSNI is still overwhelmingly Protestant. While violence did not break out in the immediate aftermath of the funeral, frustration in the loyalist community simmered in the subsequent months, realising itself in the recent riots.

Beneath the surface

The politics of recent tensions, however, is just part of a much more complicated story. Beneath the surface of border negotiations and trade agreements is a trove of competing cultural narratives; both identities are shaped by rejection of the other. For loyalists, this is expressed through the mantra “No Surrender,”; for the republicans, “Tiocfaidh ár Lá”, meaning “Our Day Will Come”.

The events of the Troubles are living memory for a large part of Northern Ireland’s population. While reconciliation has come a long way, its cities are still flooded with the hallmarks of division. Walking through a street in Belfast or Derry, the footpath on one side will often be painted in the colours of the Irish flag, the other side a Union Jack. Giant murals depicting sectarian symbols are everywhere, archiving and perhaps sustaining this dichotomy. With the referendum taking place less than twenty years since the conflict ended, Brexit stoked old fires that did not have time to fully extinguish.

For the first time since the birth of the state, the results of this year’s census are expected to reveal more Catholics than Protestants in Northern Ireland. Amid a dwindling majority, an indifferent British government, and a cultural narrative prohibiting ‘surrender’, the hegemony of unionism has ruptured. The debris of its disenfranchised ideology was evident on the streets of Belfast this month. Brexit was predicted to break the region’s hard-won peace. As recent events threaten a return to conflict, it is unclear if a solution to appease both sides is possible.

Sinéad Barry is a 2022 Master of Public Policy candidate at the Hertie School. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in English literature and Philosophy from Trinity College Dublin, where she specialised in creative writing. Sinéad has previously worked as a journalist and is interested in migration issues, gender equality, and climate justice. She loves to read, walk, and wear excessively colourful jumpers.