In the last 25 years, Venezuela has walked the path from a democratic to an authoritarian state. Having been one of the richest countries in Latin America in 1998, Venezuela is now among the poorest countries in the region with 95.5% of its population below the poverty line. Can the new reforms save the Venezuelan economy and alleviate the humanitarian tragedy?

Venezuela’s Socialist Revolution

In 1998, one of the most prosperous countries in Latin America began its path towards a Bolivarian revolution: It elected Hugo Chávez, the former commander of a rebel group during the failed coup in 1992, as president. He was supported financially by an old colonial elite that saw in Chávez’s leadership a chance to regain their political power and the path towards a more egalitarian society.

Chávez’s proclaimed socialist policies included the nationalisation of key industries and Boliviarian missions to overcome poverty and inequality. Under the slogan of “Motherland, Socialism or Death”, Chávez aimed to implement his vision of 21st-century socialism, which draws on socialist movements in Latin America, such as the Cuban Revolution, Nicaraguan Revolution and Salvador Allende’s government in Chile.

Twenty years later, Chávez’s notion of socialism had failed to deliver on its promises. Venezuela faces high levels of corruption, clientelism and authoritarianism. The revolutionary path ended up bringing more poverty, scarcity of food and medicine and reversed the country’s economic development.

One of the main reasons behind this failure was indiscriminate public expenditures. Chávez’s social policies and programmes, such as free housing, food stamps, and health care, eventually tripled government expenditure in an unsustainable way. The initial plan was to finance these programmes through income generated by a state-owned oil company called Petróleos De Venezuela Sociedad Anónima founded in 1976 (PDVSA), which represents the state monopoly of the oil industry. While this mechanism worked during the Oil Boom (2004-2009), the crash of oil prices in 2012 brought it to an abrupt halt, as the productive capability of the PDVSA was destroyed. The government then shifted to financing the costs of these social policies by artificially increasing the money supply. As the government heavily relied on this practice, it caused one of the longest hyperinflation crises in human history.

While similar countries in the region, like Colombia, are today growing at an average of 2% every year, Venezuela’s GDP is 9% lower than in 1999, without controlling for inflation. The annual GDP per capita is –19.6% after five consecutive years with a negative rate, and the annual inflation rate in 2019 was around 9585.5%. This means that once you receive your monthly wage in Venezuela, its value will decrease by 30% within 24 hours.

However, the failure of Chávez’s socialist revolution was not only about the economy. Pernicious corruption within the state institutions prevented social policies from bringing equality among Venezuelans. In 2017, the country became the most unequal country in Latin America. Its high GINI coefficient of 0.681, a statistical measure representing income inequality within a country ranging from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates maximum inequality, testifies to its dire state. Despite great hopes of socialism lowering poverty and inequality, Venezuela ended up becoming poorer and more unequal.

The Banana Republic Deprivation

The term Banana Republic refers to countries that are politically unstable and have a single product-dependent economy. Usually, a corrupt elite captures the whole rent generated by this specific product. In the case of Venezuela, the economy has been absolutely dependent on oil exploitation.

The failure of Venezuela’s regime is also explained by factors beyond financing of their socialist policies. Chávez’s regime not only attacked the country’s elite that had previously supported him, but it also built a new oligarchy – the bolichicos, a political and economic class who were enabled by the regime to capture rent through corruption and political favours. The Oil Boom allowed the regime to increase public expenditure, and the bolichicos got more valuable contracts from the state.

Recent corruption cases reflect the magnitude of the new elite’s benefits. In 2013, federal legislators revealed that the National Commission for Foreign Exchange (CADIVI) embezzlement was around $59.000 million. Three years later, in 2016, the National Assembly of Venezuela investigated the PDSVA for corrupting $11.000 million. In January 2021, Swiss prosecutors froze bank accounts that had collected more than $10.000 million from the public funds of the country.

While the bolichicos became billionaires, national welfare and production declined. They transformed the concept of a corrupted elite that benefits from primary sector economies and corrupt institutions into a “how to bankrupt a petrostate and become a billionaire in the process” handbook.

The Reform: From Socialism to Corporativism

In 2013, Chavez’s vice president and loyal disciple, Nicolás Maduro, was elected president in heavily contested elections following Chávez’s death. Ever since, Venezuela has been immersed in political turmoil. After Maduro had continued Chávez’s socialist legacy and increased repressive state policies, external pressure forced the regime to readjust its policies. Maduro’s regime was forced by foreign sanctions to implement an economic reform in 2019, which seems to transform the socialist economy into a free market economy without changing the authoritarian regime. The bolichicos pressed the government for this reform to maintain their businesses, trying to consolidate new monopolistic companies in a “free-market” economy, as the sanctions were undermining their current businesses.

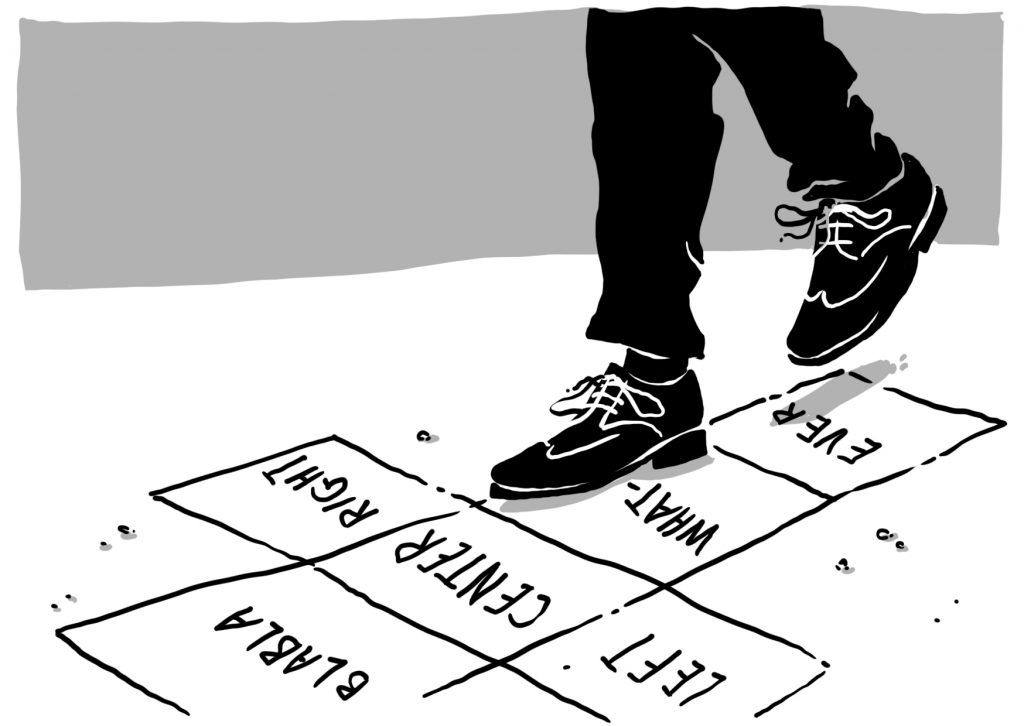

Maduro’s reform intended to alleviate the economy and to improve the well-being of some people in Venezuela, relieving taxes and giving economic incentives to this new elite without giving away political or economic power. However, this has created some disputes between regime officials. While Maduro is talking about dollarisation and lowering import tariffs, Iris Valera (Vice President of Chavista National Assembly and Member of Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela) is calling for price control measures and higher taxes. Rather than opening the Venezuelan economy, however, the reforms have brought instability by pushing different actors of the regime into a turf war. While the socialist wing of the regime is struggling against the reform, Maduro continues to rely on the bolichicos for support.

The most likely outcome of the current reform negotiations is a superficial reform that allows the bolichicos to carry out their businesses without competition. The democratic oppositions have been heavily prosecuted and forced into exile. It also allows the socialist wing of the regime to control small companies and their means of production. Venezuela will, therefore, continue to remain a poor and unequal country. Maybe better than yesterday, but not good enough to be called developing.

Incremental Change?

Although very unlikely, some independent political actors in Venezuela, like workers’ unions and industry representatives, see this reform attempt as an opportunity to democratise political institutions in the long term. Fedecámaras (the industry representatives) have engaged in negotiations with Maduro’s regime, intending to promote bills that could start a path to institutional democratisation. A market-based liberal economy would guarantee private property and stabilise the economy.

The negotiations have not been successful, and Maduro has so far ignored their proposal. Nevertheless, it is plausible to think that it might alleviate the poorest section of the population if the negotiations eventually succeed. If Venezuelans get some relief from the economic reform, it will allow them to focus on their struggle for civil rights instead of focussing on meeting their basic needs, such as having enough food for lunch.

Venezuela is facing a deep political and economic crisis. The failure of Chávez’s socialist project and the international sanctions against the regime have forced President Maduro to initiate economic reforms. The country must end the subsidisation of the rich bolichicos elite to implement reforms that allow everyone to enter the market and ensure equality among citizens.

Alejandro is an Urban Planner of the Simon Bolívar University, Former Youth Secretary Board of Primero Justicia, Scholar of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, and an MPP Student at Hertie.

Alejandro is an Urban Planner of the Simon Bolívar University, Former Youth Secretary Board of Primero Justicia, Scholar of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, and an MPP Student at Hertie.