Fluorescent empty shelves, stocked only with anxiety, were the initial COVID-19 pandemic reality-check for many. Consumers and businesses were blindsided; their normal lives and operations shattered. The world immediately felt the fallout of disrupted supply chains, many of which have not yet recovered.

So long as orders were fulfilled cheaply and efficiently, consumers and businesses did not have to think too deeply about how products ended up on store shelves. Just-in-time (JIT) supply chain management was the golden goose of logistics, minimizing inventories by ordering and receiving shipments only as needed. And yet, JIT proved to provide little cushioning in the event of unexpected disturbances. By the time the widespread repercussions of the JIT model manifested themselves in 2020 in the form of missing FFP2 masks and empty toilet paper shelves it was already too late.

Amidst the chaos of the pandemic, a rare opportunity for the radical restructuring of supply chains has arisen. There is now a need for stakeholders to collaborate, regulate, and utilize decentralized forms of organization to mitigate the impact of future supply chain disruptions. But first, where did it all go wrong?

At the end of January 2020, China’s factories locked down, impacting 94% of Fortune 1000’s Tier 2 suppliers. Tier 2 suppliers are crucial for transforming raw materials into component parts and when they can’t get the products, neither can most of the world’s downstream business. By mid-February, week-over-week international trade transactions with China had halved.

Across the globe, populist politicians rode a wave of nationalist rhetoric calling for the restrengthening of supply chains by way of “reshoring,” that is, moving suppliers of crucial goods back within domestic borders. However, the process of scaling domestic supplier infrastructure is neither a quick nor simple solution. Nevertheless, reconfiguring logistic networks creates a wealth of opportunity for organizational innovation.

Risk-proofing supply chains: opportunity or headache?

Identifying vulnerabilities and risk-proofing supply chains is necessary to avoid future disruptions. This requires time and resources to set up infrastructure that can collect data from different suppliers, distribution centers, and transportation hubs. Real time information needs to be captured, monitored, and shared to allow for disruptions to be anticipated and mitigated. Weak links and single source suppliers need to be identified and redundancies put in place.

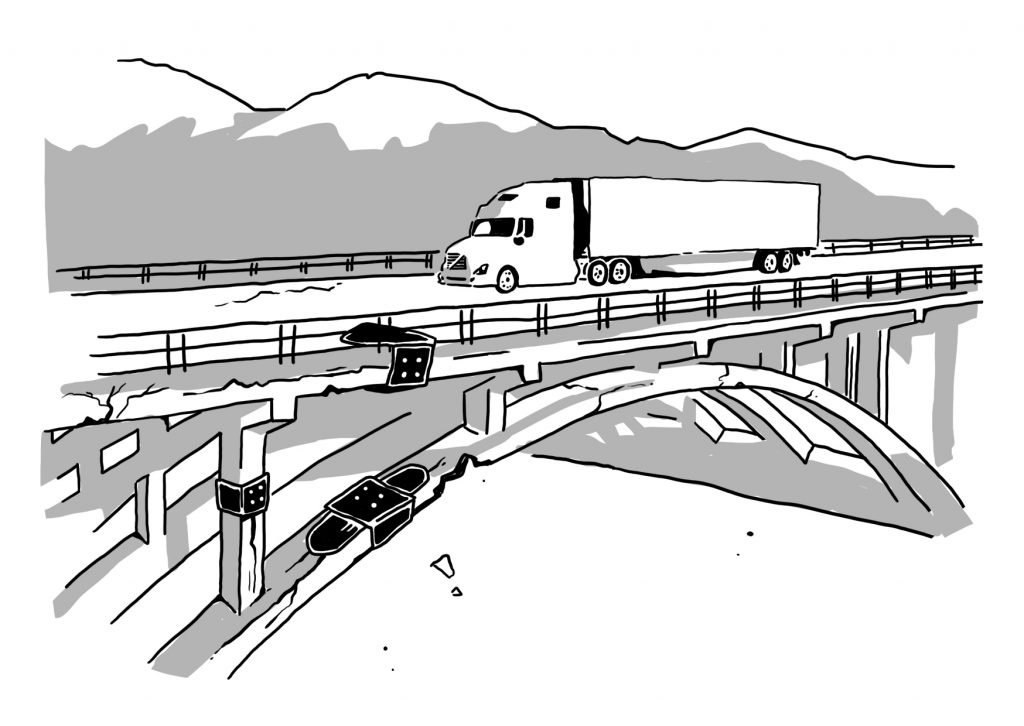

Currently, this is perhaps an impossible task. Vulnerabilities extend well beyond the impacts of infectious disease. Natural disasters, labour strikes, military conflict, and trade frictions can also imperil supply chains. Simply put, most companies do not have the capacity to trace the vulnerabilities of all specialist suppliers and subcontractors at every tier of their supply chain.

Aggregating channels of information presents an opportunity to mitigate supply chain risk. The concept of the fourth industrial revolution (Industrie 4.0), introduced by the German government in 2011, is characterized by the automation and interconnectivity of smart manufacturers. ‘Lights-out’ factories that use sensor-equipped automated guided vehicles (AGVs) and drones to produce goods with little-to-no human intervention are steadily emerging. The vast amounts of information gathered and communicated machine-to-machine (m2m), tier-to-tier, to transportation and distribution facilities, to governments, and to consumers, necessitate a new generation of industrial organization.

Blockchain’s role in the supply chain

Distributed ledger technology (DLT), better known under the generic label “Blockchain”, enables all of the different nodes in the logistics web to communicate information simultaneously. This can be performed in an increasingly more efficient and transparent way than the current industry standard (enterprise resource planning systems, or “ERPs”). Blockchains use a decentralized, peer-to-peer network of computers which can verify, organize, and preserve information. The decentralized power structure is a radical form of information governance which can build and maintain trust among all levels of the supply chain, assist in the automation of a concatenation of processes, and facilitate data interoperability.

One of the main contentions is the private versus public Blockchain debate. Private Blockchains require permission to access, meaning there is a limited number of nodes on the chain which ensures a constant speed. On private Blockchains, not everyone who has access can publish a block and in some cases, authorities can delete blocks. On the other hand, public Blockchains can be accessed by anyone, are fully immutable, and the more nodes on the network, the greater equality of member’s rights. However, a considerable drawback of public Blockchains is their large environmental impact and, as if farcical, how Bitcoin uses more energy per annum than Argentina.

Since the inception of Blockchains, many features have been developed which facilitate instantaneous decision making throughout the network, allowing for logistic processes to be managed with minimal human intervention. For instance, smart contracts which became natively embedded in Ethereum automate processes based on ledger conditions.

Notably, smart contracts have the added ability to identify and track the manufacturing process of each unit of goods. Consider a semiconductor: as soon as it passes quality testing at its manufacturing facility, a smart contract could be executed to pay the supplier for that specific unit. This results in lower barriers of entry, as manufacturers wouldn’t make deals solely based on the size of contracts, and it creates precise and verified information accessible to the entire network.

A main upside of a public Blockchain is the access to insights it gives to stakeholders who would have otherwise not been invited to the decision-making table. Governments could tax goods more effectively with geospatial information; competitive businesses could respond more quickly to fluctuating market demand; and end consumers wouldn’t be at an informational disadvantage. Another upside of public blockchains are their ability to address growing privacy concerns and the subsequent need for data protection. This is made possible via zero knowledge proofs, which can shield sensitive information and adhere to Article 25 (“Data Protection by Design”) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

In theory, a consumer could use an app to interpret a public Blockchain, whereby the app could scan the barcode of a product and have it display information about the products’ supply chain in a format that’s readable to humans. This could guarantee that agricultural crops meet health inspection standards or that rare earth metals are collected in accordance with safety laws. In short, it means more accountability for all stakeholders involved in the manufacturing, selling, and consumption of the good.

Intelligent smart contracts use a more advanced algorithms, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Machine Learning (ML), to facilitate fair trade practices like revenue sharing or price-adjustments at different tiers of the supply chain. This would eliminate human management costs and latency, creating efficiencies which could lower prices for consumers.

However, as the Canadian Competition Bureau and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have recently noted, this technology also faces the possibility of collusion and anti-competitive behaviours that are detrimental to consumer welfare. For instance, a public Blockchain could create trust between oligarchs and smart contracts could be used to punish any deterrence from any collusion agreements regarding price or outputs. AI/ML could also be used to tacitly coordinate price-fixing, without competitors’ explicit communication. Experts at the OECD recount how publishing real-time petrol prices online subsequently led to price increases in Germany, Australia, and Chile.

In order to incorporate Blockchain into complex global supply chain networks, a global set of standards that are agreed upon by vital supply chain industries is needed. Certain interest groups, such as the Blockchain in Transportation Alliance (BiTA), are engaging shareholders already and the World Economic Forum (WEF) has written numerous white papers detailing what the widespread implementation of Blockchain could look like.

Early collaboration for a sustainable future

The manufacturing and consumer products industry is now dominated by companies that are in the early stages of implementing AI/ML. It’s pivotal for stakeholders and regulators to collaborate and establish rules from this initial stage of the technology’s infancy, rather than trying to enforce terms and conditions after governments and businesses have already implemented competing rules regarding its governance. Failing to do so could result in widening the existing antitrust-grey-area.

Despite the considerable setbacks, the pandemic has also revealed tremendous opportunities for growth. To go back to traditional supply chain management is not only careless, but would also be a disservice to future generations who will face great disasters of their own. Industry needs to embrace Blockchains that enable transparent and efficient information organization. Stakeholder trust and collaboration is necessary in the development of a robust network that can act as an early warning system for future supply chain disruptions to come.

Thomas Jestin is an MPP candidate at the Hertie School from Canada, interested in digital disruptions, emerging tech, and privacy policy. Thomas completed his undergraduate in Contemporary Studies and Political Science at University of Kings College and Dalhousie University.

Thomas Jestin is an MPP candidate at the Hertie School from Canada, interested in digital disruptions, emerging tech, and privacy policy. Thomas completed his undergraduate in Contemporary Studies and Political Science at University of Kings College and Dalhousie University.