While the United States presidential election has attracted worldwide attention, the phenomenon itself must not distract from its vast foreign and domestic policy implications. One example is the historic Colombian Peace Agreement which urgently requires financial and political assistance from US Congress to calm the waters in Colombia and to avoid spillage beyond its borders.

Four years ago, a historic Disarmament, Demobilisation, and Reintegration (DDR) agreement was signed to overcome the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), the country’s most powerful rebel group. The crude fact that the deal came about following three failed peace attempts was a remarkable achievement, earning President Santos the Nobel Peace Prize.

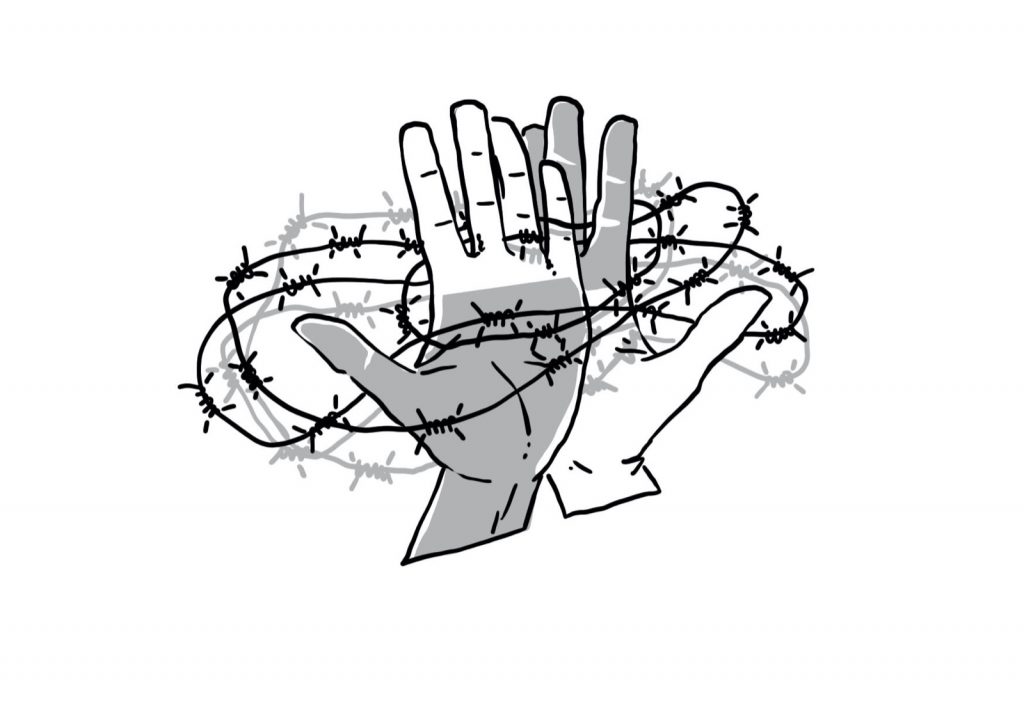

For over half a century, Colombians have endured a multi-actor conflict over control of the population, land, natural resources, political power, and drug trafficking. The rebels had waged a bloody war with successive governments for decades. Patterns of violence against civilians have also included forced disappearances, extrajudicial and summary executions, sexual and reproductive violence, forced recruitment of minors and inhuman and degrading treatment. Whether by change of heart or suspended feelings, in November 2016 the FARC signed a peace accord while handing in 7,000 of their weapons to United Nations (UN) inspectors. Almost from one day to another, five decades of armed conflict that cost over 220,000 lives and displaced more than 7 million people ended with a whim, not a boom.

Four years later, however, the peace process seems to tremble. After an initial phase of demobilisation and disarmament, implementation has faltered. Criminal activities are mounting again and several paramilitary groups have reemerged. According to Colombia’s Institute of Studies for Peace and Development, more than 700 community leaders have been killed since 2017. About 1,800 guerilla fighters are back in business. More than ever, financial and human support is crucial to a happy ending. After all, peace and stability secure the future of the country with its 50 million inhabitants, but also serve to avert the spillover of transnational criminal activities, such as drugs and arms trafficking.

Multilateral peace and progress efforts have paved the way for the next crucial part of the peace process: the reintegration of nearly 50,000 guerrilla operatives into a decent civil-society life away from crime while making it easier for the government to win the war on drugs. Without a peaceful and comprehensive transformation of the vast formerly rebel-controlled areas including the impenetrable Colombian mountains, the government will neither be able to prevent the deterioration of Colombia’s security situation, nor to stifle violence, delinquency and crime.

Inactivity and lack of support to countries like Colombia would translate into more weapons, drug trafficking, and illicit exploitation of natural resources with terrible implications for DDR planning processes. This cannot be an option on the table in US foreign policy. Above and beyond the merits of improving the situation on the ground and not wasting prior achievements nor previously invested resources, sustainable progress in Colombia is an essential US strategic interest.

In the US, there has been a longstanding bipartisan consensus on supporting peace in Colombia. Both goals, peace and full territorial control, have been defended for the last 25 years as the two governments are linked through several key issues. Adding to the fight against drugs and terrorism after 9/11, the US has promoted respect for human rights and the rule of law. At the inception of “Plan Colombia”, a $10 billion US Congress campaign that provided financial, military, and training resources to tackle Colombia’s armed insurgents, the scale of US aid towards Colombia was greater than for any other country except for Israel and Iraq. In fact, the US embassy in Bogotá hosts representatives of the seven US army bases in the country, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the US Agency for International Development.

By the end of Plan Colombia when the historic peace agreement with the FARC was signed, the country had seen a large drop in homicides, kidnappings and massacres. To secure this achievement, the US has provided more than $1.2 billion in aid to Colombia since 2017, with over $300 million for anti-narcotic efforts. However, the Trump administration has altered the US support of the peace deal and, instead, only pushed for a hard-line coca eradication strategy. Trump has criticised Colombian President Ivan Duque for not doing more to fight the drug trade and threatened to decertify Colombia as a partner in the war on drugs.

The Integrated DDR Standards (IDDRS) in Colombia have been formulated through the joint efforts of 26 UN entities. Though not every previous effort has been satisfactory, cutting down on certain programs and initiatives would negatively affect Colombia first and foremost. Rather, the full-fledged goals of the recently modernised IDDRS require more resources and significantly higher investment. The fact that not all goals were consolidated in recent years puts the Colombian Peace Agreement in jeopardy.

With the incoming Biden administration, hopes are growing that US support will not decrease regarding real policy and instead commit to fully implement all aspects of the peace accords, including crop substitution and rural development to solve the underlying social and economic problems. In fact, President-elect Biden, who had already touted his support for Plan Colombia as Vice President, in an op-ed published on October 7 called it “one of the most successful and bipartisan American foreign policies of the last half century”.

In short, financial and political support is essential to save the most profound and widely reached peace agreement in the Americas. With over one million Colombian Americans and the US being the world’s top consumer of Colombia’s cocaine, Colombia’s drug policy and the future of US foreign policy are mutually dependent.

US Congress must assume responsibility and bolster the Colombian peace process both because of national interests and for regional stability.

So far, the war-peace saga in Colombia has yielded a number of lessons learned. One is that following the completion of the disarmament stage, former combatants will remain watchful and suspicious of the government’s intentions in temporary demobilisation zones. The delicate situation on the ground requires reinforced police and military forces to stay in the vulnerable regions for the next few years to assure peace and stability.

Global responses continue to call for unified efforts. But regional politics and policy, particularly in the US interests on ‘back-yard’ ceasefire and economic growth, mean harnessing peace-building efforts while supporting communities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from the effects of the pandemic in the future. Armed groups like FARC, which have left a legacy of violence, drug expansion and criminal networks should be eradicated through transnational efforts promoting local ownership and transitional justice.

Colombia is in the complex process of implementing a comprehensive peace deal that terminates 56 years of internal conflict with the country’s biggest guerrilla group. To end it, the Colombian state and FARC agreed not only to stop the fighting but also to prevent a return to violence by addressing the underlying causes of the conflict – rural poverty, insecurity, and lawlessness. The next phase of the agreement, centred on the human dimension, includes seeking the rights of the nearly 8 million victims to truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-repetition. Likewise, it encompasses the social and economic reincorporation of the former rebels into civil society and the democratic process.

The heavy demands of addressing the multiple challenges of reintegrating ex-combatants, tackling illicit drug production, and fighting reorganised armed groups simultaneously are naturally overwhelming the government’s capacity to keep the process on track. A robust reconciliation as an effective means for peace and security is worth protecting. It deserves active support from the US and continued monitoring from UN member states. The agreement was a unique achievement that must raise the awareness of civil society in Colombia and beyond to pressure the new US administration to invest in the implementation of the Peace Agreement. Otherwise, 25 years of continuous support worth $20 billion, human resources and lives would have been wasted, as peace and stability remain fragile. The ambitious but essential goal to address the root causes of conflict and fulfill victims’ rights requires political commitment and financial support from the US Congress.

Whilst finishing his Master’s in International Affairs at the Hertie School, Raúl Carbajosa Niehoff works as a desk officer at the policy department of the German Federal Ministry of Defense. He is most interested in international security and defense policy, geopolitical rivalry, armed conflict and military intervention with a regional focus on Eastern Europe. Raúl likes socialising and retreating alike.