“A country without a patent office and good patent laws is just a crab and can’t travel any way but sideways and backwards,” wrote American novelist Mark Twain. A patent formalises the right of the innovation to belong to the inventor, excluding others from producing it. As a result, intellectual property rights and patenting have been the cornerstone of safeguarding inventions.

Patents motivate and assure an inventor that they will be positioned to reap the benefits of their ideas. Our modern economy is only as good as the resourceful solutions brought about by innovation. And so, nations institute patent offices to protect intellectual property law through trademark, copyright, and patents. Inventors, individuals or corporations can seek patents on any invention as a legal safeguard in their business model.

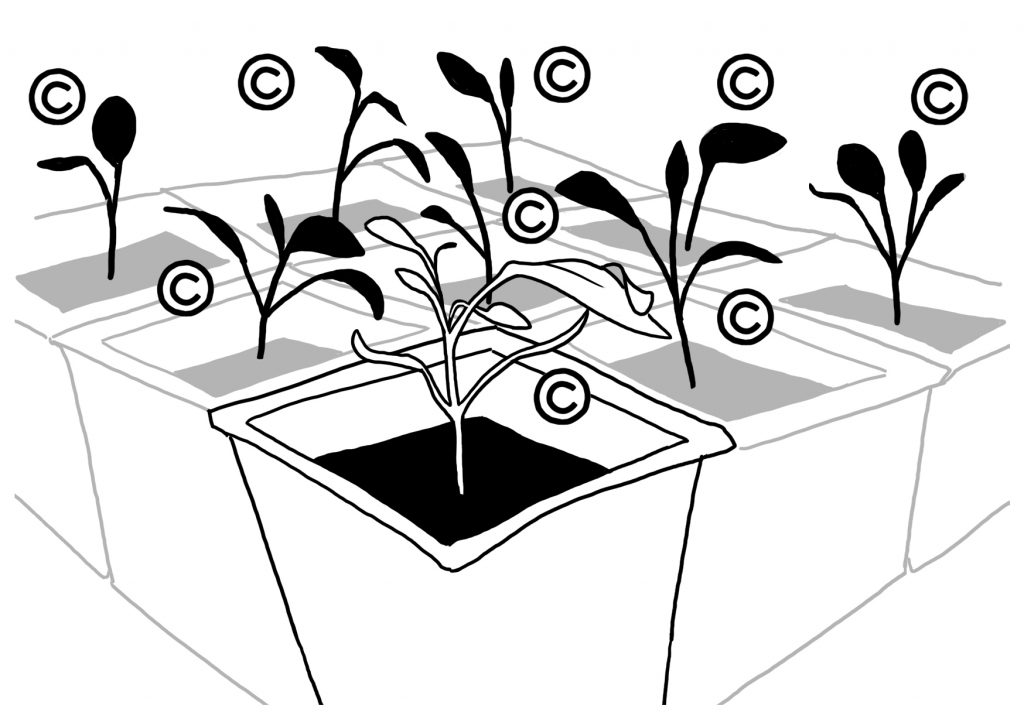

The question that naturally arises, then, is are all innovations truly patentable? Since the mid-80s, agro-chem corporations have been seeking patents for hybrid seeds, although original patent laws explicitly excluded the patenting of biological processes, including plants and animals. Whether seeds are a global commons’ resource gifted to humanity by the universe’s evolution, is a question for a bioethicist, but a simpler consideration is whether seed patenting poses a threat to global food security.

The Giants of the Global Seed Market

The paradox of industrial patents is that in safeguarding research and innovation, they also, in turn, enable monopolies that undermine creative development. The rise of seed patenting has caused a shift in the rights over seeds from the hands of farmers to the hands of multinational agrochemical corporations. Hybrid seeds that came to prominence in the 1930s birthed the venture capitalist fields of biotechnology and genetic modification in plant research. In 1995, US plant patent regulations limiting the distribution of patented hybrid seeds were incorporated into international law with the TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) agreement. Under the TRIPS agreement, farmers now had to pay royalties on genetically modified seeds (patented seeds) for farm-saved seeds. Seed-saving is the common practice of storing seeds from successful crops for future use. As seed patent law excludes “others” from using, producing, or distributing seeds, farmers found themselves in the unique position of owing money to agro chem corporations for the seeds that they collected from their own crops.

Seed-saving allows growers to develop gene-diverse seeds that are more adaptable to the local environment’s demands. With the enforcement of seed patents, seed ownership has been centralised from farmers’ individual seed storages to being owned by the top four seed firms: Bayer, Corteva Agriscience, ChemChina, and Limagrain. A 2018 analysis revealed that these top four seed firms held a 66.5% share of the global seed market. – a steady increase from ten years prior, in 2007, when these firms controlled 47% of the global seed market. The monopolisation of the global seed market is causing plant gene erosion and farmer corporate-serfdom.

Seeds over Genes: Patents and Biodiversity Loss

75% of the world’s food is produced from 12 plants, most heavily from corn, wheat, rice, and soybeans. Patent protection, such as on the genetically modified versions of these four plants, that prohibit farmers from saving seeds, is causing alarming gene uniformity. This lack of gene diversity in 75% percent of the world’s food supply makes us particularly vulnerable to a worldwide crop failure. Seed gene diversity, and biodiversity in general, is the best line of defense against a global food crisis. Governments and international organizations such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO) need to push back against agrochemical corporations’, such as Monsanto’s (now Bayer Crop Science), claims that patent-protected genetically engineered seeds are “vital to meeting the world’s growing food needs”.

Ensuring global food security is a big undertaking in which large multinational agro chem corporations might be helpful players (after all, big problems need big solutions). At the same time, however, we need to recognise that these corporations’ business interests might clash with achieving food security. Seed patenting reduces biodiversity by prohibiting seed-saving, yet seed patenting financially benefits corporations. In this conundrum, the business model of agro chem corporations is at odds with their very own claims of “feeding the world”.

Seeds for our Future

At a plenary session on October 16th, 2019, European MEPs agreed on a new non-legislative resolution that curtailed the patentability of plants or animals, citing “ Patent-free access to biological plant material is essential to boost innovation and competitiveness of the European plant-breeding and farming sectors, to develop new varieties, improve food security and tackle climate change”. Governments have a mandate to get involved in economies and the trade of goods when there is a threat to national security.

A common saying in politics is that everything and anything can be made into a security argument. Politicising seed rights on your own balcony or in your backyard as a food security issue is not mere sensationalisation. Rather, it is a plea to join the agricultural-technology and biotechnology policy debate. Policy school classrooms and government building halls could not be more apart from crop fields or livestock herds, but ignoring agriculture and rural life is a gross oversight that puts at risk our nations’ well being. Seed patenting is one such agricultural and food-related policy that deserves scrutiny. Countries have long depended on patents to stimulate private investment for innovation, but seed patenting and the consequence of the consolidation of the global seed market is an example of where applied intellectual property rights go too far and end up undermining innovation – in this case, innovative gene diversity in seeds.

The well-known American patent lawyer, Giles Sutherland Rich, once said: “ The good patent gives the world something it did not truly have before, whereas the bad patent has the effect of trying to take away from the world something which it effectively already had.” Seed patents have criminalised the capacity of farmers to collect seeds and cultivate seed biodiversity. They are curtailing the potential of each farmer, gardener, or urban-balcony tomato grower to be their own plant gene diversity incubator.

Francesca Ractliffe is a foreign-born British-American who studied theology under the Jesuits at Georgetown University and whose curiosity has taken her to jobs in journalism, arts, business, and US congressional politics from the North African heat of Morocco and Egypt, to the swampy humidity of Washington DC. She recently has swapped one nation’s capital for another, having chosen to pursue a Masters of Public Policy in Berlin. She is the co-president of the Grand Strategy Club at the Hertie School.