To avoid domestic food price spikes during COVID-19 lockdowns, major agricultural producers such as Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia temporarily capped exports of staple crops. The resulting market distortions underscored import-dependent countries’ vulnerabilities to food supply disruptions. Beyond the risk of short-term shocks, global food security is seriously threatened by long-term climate trends. Large populated areas in the Americas, Africa, and Asia are vulnerable to desertification processes exacerbated by climate change, as well as industrial agricultural practices that cause soil infertility and deplete groundwater reserves. Groundwater is the world’s most extracted natural resource, and agriculture accounts for nearly three-quarters of total groundwater usage.

Coming decades will witness climate-induced food scarcity pressures, along with a strategic scramble for control of arable lands. Some of the most water-stressed and import-dependent nations are also among the most proactive in pursuing food security as a national security objective. Resource-rich Asian countries that face desertification at home are snapping up agricultural assets abroad in more fertile, groundwater-rich countries.

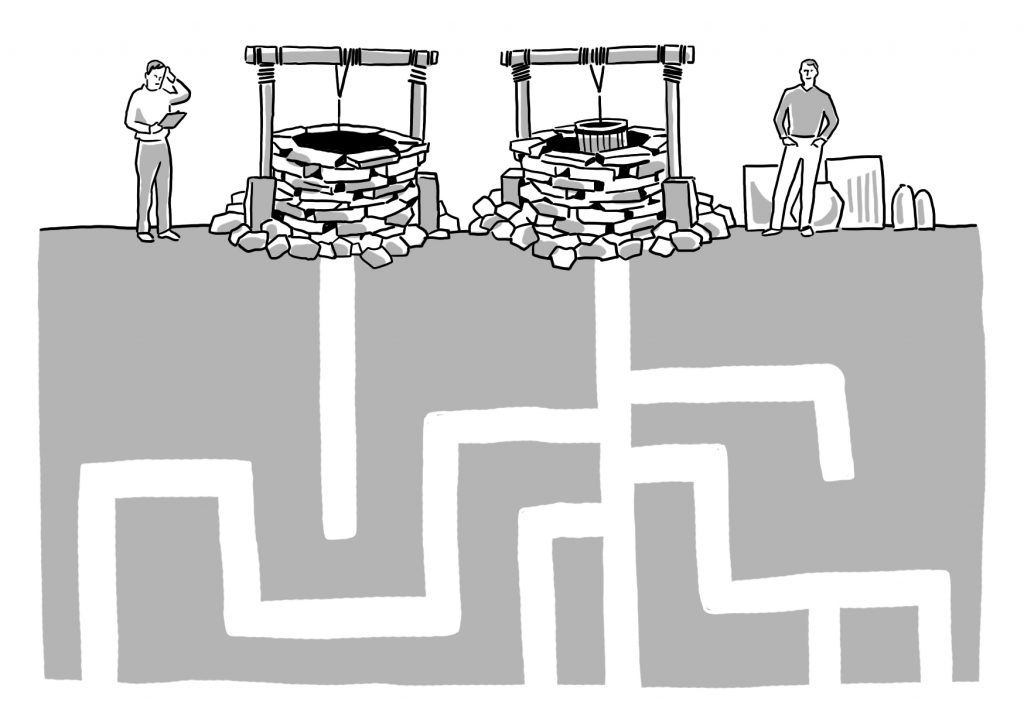

Large foreign-owned commercial farms impose significant negative externalities for local communities’ agricultural and ecological sustainability. Extractive agriculture drains natural resources: soil quality is degraded by nutrient loss, and the underground water table is depleted beyond the replacement rate. The second of these problems is less visible and thus harder to measure, but it is certain that the global water table is declining. Groundwater reserves in some areas – including parts of Spain and Italy – could go dry by mid-century. In December 2020, water futures began trading as a commodity on US stock markets for the first time. Market speculation around a natural resource reflects the expectation that water will become more scarce over coming decades due to natural as well as anthropogenic factors.

In the context of these upcoming precarities, land-rich European countries cannot afford to take domestic food security for granted by allowing their agricultural resources to be acquired by foreign investors. Europe is the continent least vulnerable to desertification, which makes its agricultural assets especially attractive investments. Several EU Member States, Germany among them, do not restrict the purchase of agricultural land by foreigners. The long-term risk is that foreign-operated commercial farms could contribute to the depletion of Europe’s groundwater resources, without contributing to the food security of European citizens. Europe’s verdant bucolic landscapes could undergo an irreversible transformation to arid land. Accordingly, Europe must regard groundwater sovereignty as an urgent strategic issue.

Saudi Arabia’s Agricultural Investments in Ukraine: A Rational Response to Domestic Resource Scarcity

With its desert climate and growing population, the Arabian Peninsula is one of the regions most vulnerable to food scarcity pressures, but government investments in food security have positioned the Arabian Peninsula as one of the regions best prepared to meet its nutritional needs in the event of global shortages. The proportion of food grown locally has increased in recent years due to the adoption of agricultural technologies like hydroponics. Yet, Arabian Peninsula countries remain overwhelmingly dependent on food imports. Past efforts to produce staple crops locally resulted in an unsustainable depletion of the Arabian Peninsula’s groundwater reserves. This led Arabian Peninsula governments to develop an understanding of agricultural self-sufficiency that relies on food produced abroad, at agricultural installations owned by sovereign wealth funds and other public investment vehicles.

Being the most populated Arabian Peninsula country, Saudi Arabia is particularly active in the scramble for agricultural resources. Saudi Arabia’s agriculture investment fund, SALIC, controls land assets on six continents. SALIC’s investment strategy prioritises high-yield commercial holdings in twelve staple nutritional categories, “selected on the basis of their strategic importance in ensuring long-term food security.” In parallel to its farmland acquisitions, Saudi Arabia is expanding its logistics networks, opening sea lanes for trade with Asia, Africa, and Europe. Among other strategic benefits, this provides direct access to output from agriculture holdings abroad and minimises the potential for food supply disruptions.

Saudi Arabia is increasingly interested in Europe’s Black Sea region, which offers cheaper investment opportunities compared to Western European or North American markets. Trade and investment flows, as well as diplomatic ties, are expanding. When Saudi Arabia introduced its first tourist visas in September of 2019, citizens of Romania, Bulgaria, and Ukraine were among the 49 nationalities eligible to obtain visas upon arrival. Earlier in 2020, Saudi Arabia’s new foreign minister chose Bulgaria for his first official visit to Europe, and accepted an invitation to visit Ukraine for political consultations.

Behind this rapprochement is the envisioned role of the Black Sea in ensuring Saudi Arabia’s food security. SALIC designates the Black Sea as a favoured investment destination for wheat, barley, soybeans, corn, green fodder, and red meat. The Black Sea is also geographically proximate to the Arabian Peninsula, with short transit times and low freight costs for agricultural cargoes. Saudi Arabia has also invested in Ukrainian port infrastructure to consolidate access to Black Sea shipping lanes.

Ukraine, known as the breadbasket of Europe, is the world’s seventh-largest wheat producer with an annual output around 29 million tons. Albeit not in the top ten, Romania and Bulgaria are among the fastest-growing wheat exporters in the world. Through subsidiaries, SALIC has acquired nearly 250,000 hectares of Ukrainian farmland over recent years. SALIC now controls almost 4% of Ukraine’s total wheat production, making it one of the biggest farm operators in Ukraine. In April, the state grain buyer, Saudi Grains Organization (SAGO), made its first purchase of wheat from SALIC’s Ukrainian holdings, an order of 60,000 tons.

The Lesson for Europe: Groundwater Sovereignty is a Vital Strategic Issue

Saudi Arabia is far from the only player in the global agricultural investment race, nor are SALIC’s European assets confined to the Black Sea region. All six of the Arabian Peninsula governments face common climate-related pressures to acquire agricultural assets abroad; Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait are especially prolific investors. China, too, is feeling the pressures of desertification and is acquiring agricultural assets in Europe through the Belt and Road initiative. Albeit lawful in nature and ostensibly peaceful in intent, such investments effectively happen at the expense of Europe’s control over its own natural resources. In the context of these global developments, should Europe more closely review foreign agricultural investments?

Europe’s environmental policy should limit foreign ownership of groundwater-intensive industries such as agriculture. The existing legal regime for groundwater protection, the EU Water Framework Directive (2000), sets technical requirements for water quality monitoring and industrial pollution levels but makes no mention of sovereignty over groundwater. Beyond an approach to groundwater sovereignty as an intra-EU technical concern, the EU should propose a principles-based charter, open to the entirety of the European continent, for protecting Europe’s water table as a precious and scarce natural resource. The charter should set minimum standards for groundwater sovereignty while leaving state parties free to impose tighter protections if they wish. The EU should encourage major agricultural producers — Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia — to become state parties to the charter.

There is already a trend in Europe towards greater scrutiny of foreign investments as a national security consideration. In 2020, Germany tightened its laws, the EU introduced a coordination framework for investment review, and the UK government is seeking broader veto powers over foreign investments. This is a favourable moment to amend national agricultural investment laws to incorporate groundwater sovereignty.

European countries should prioritize supporting family farms, to limit the farms’ incentives to sell to foreign-controlled corporate conglomerates. Last year, thousands of farmers protested throughout Germany to warn that the cost of EU agricultural regulation is making their business model unprofitable. Germany lost 16% of its farms over the decade from 2007 to 2017: when family farms go out of business, they are not replaced by another family farm, but rather by a large-scale commercial operator. Unless European countries like Germany take immediate steps to ensure the survival of family farms, the question of who might own these agricultural lands in the future, and on whose behalf their resources would be utilized, will remain unclear.

Emma Louise Leahy is an American who has worked in the public sectors of Saudi Arabia and Switzerland, which initiated her to the etiquette of two very distinct coffee-break cultures. She has also been a congressional advisor in Washington DC, where local cultural preference overwhelmingly favours the happy hour. At Hertie, she is president of the Grand Strategy Club, a fully woman-led initiative. She is a 2022 MIA student and holder of the International Security Policy scholarship.