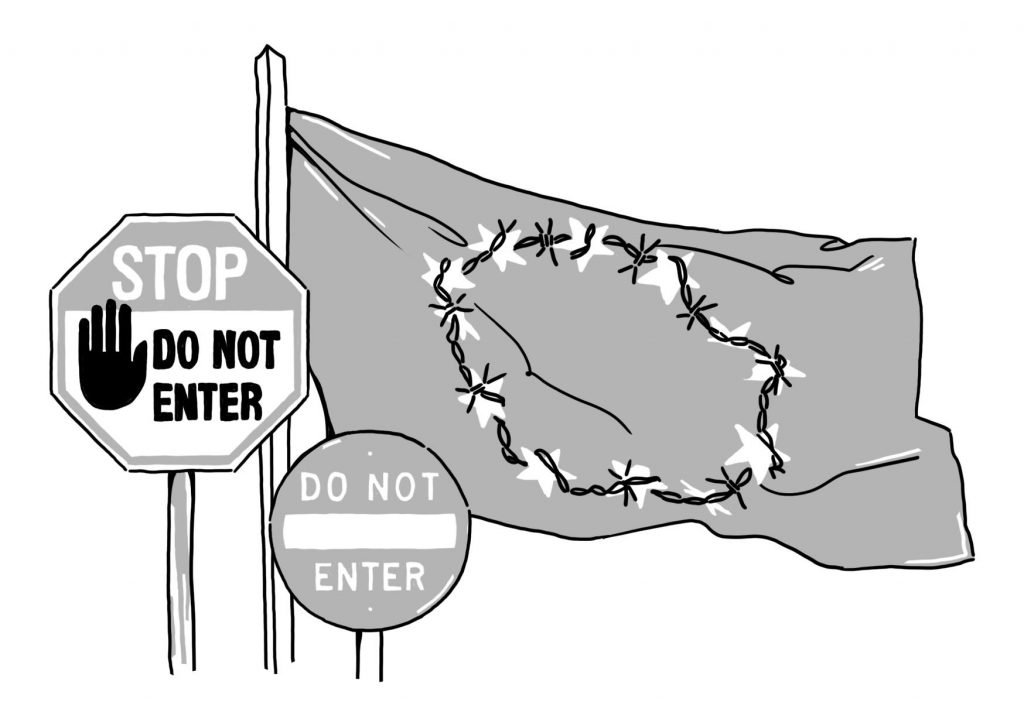

By sealing off its borders and inhumanely detaining migrants at secret locations through extrajudicial means, Europe has compromised its values and adherence to international law. Is this the EU’s last chance to respond with compassion to the arrival of people fleeing conflict and persecution?

In 2016, the European Union paid Turkey 6 billion euros to keep the door to Europe bolted shut, effectively preventing asylum seekers and refugees from becoming a European problem. A joint statement at the time stated that the EU and Turkey would work together “… to improve humanitarian conditions inside Syria, in particular in certain areas near the Turkish border”.

Nearly four years after that joint statement was issued, in February 2020, Turkish authorities were reported to have transported thousands of migrants to the Greek-Turkish border to dismantle a border fence. In response, Greece deployed major military forces to the border. Many migrants are now stuck there waiting. On March 3, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced that Greece had temporarily suspended asylum applications and allowed for immediate deportations by invoking Article 78.3 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to justify its provisional measures – an extraordinary act of deterrence and a blatant violation of international law.

Instead of offering immediate humanitarian aid at the border, the EU announced that it would launch a rapid border intervention with 700 officers from the European Border and Coast Guard standing corps. At Greece’s request, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen wants to allocate 700 million euros to upgrade the border infrastructure of Europe’s “aspida”(Greek for ‘shield’). The FRONTEX intervention squads include military-grade thermal-detection vessels to protect the EU’s external borders and send illegal migrants back with force.

The recent escalation at Greece’s sea borders in the Aegean presents only one of the many instances that expose how the EU compromises its values and adherence to international law. Can Europe still respond with compassion to the arrival of people fleeing conflict and persecution?

International Law on the Ground

Captured, beaten, and expelled. Refugee facilities on Greece’s Aegean islands are already severely overcrowded. In March 2020, the New York Times reported on the so-called “black site” detention centre in northeastern Greece. The Greek government allegedly detains asylum seekers at a secret extrajudicial location before expelling them to Turkey without giving them a chance to claim asylum or speak to a lawyer. This practice of refoulement is strictly illegal under international law. Syrian Kurd software engineer Somar al-Hussein described the current situation at the border. “To them, we are like animals.”

The right to seek asylum in the European Union is enshrined in both EU and international law. Article 14 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises the right of persons to seek asylum from persecution in other countries. Article 18 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights designates the right to asylum and binds all EU member states in reference to the 1951 Refugee Convention. Greece is, as an EU member state and a signatory of the Refugee Convention, bound to accept and to process applications of those eligible for international protection. There is no legal basis for Greece to justify ceasing to comply with its legal obligations towards asylum seekers.

Consequently, the UNHCR condemned the criminalisation of irregular entry in these circumstances and concluded that “neither the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees nor EU refugee law provides any legal basis for the suspension of the reception of asylum applications”.

The EU’s migration policy traps asylum seekers in the borderlands of Europe. People in dire need of humanitarian aid are rendered criminals and left in no man’s land without any status, access to food and shelter, or medical care.

Greece, in flagrant disregard of its legal duties, announced in March that its armed forces would conduct exercises with live ammunition near the Evros border. And they did. Human Rights Watch and other news outlets reported the excessive and disproportionate use of force, including tear gas against women, men, and children. The Greek government claimed they face organised attacks by asylum seekers and migrants trying to cross into Greece. The language and actions of the Greek authorities demonstrate an unknown level of escalation in dealing with this humanitarian crisis.

Fortress Europe or EU Asylum System?

The beginning of the Syrian civil war led people to flee their war-torn home countries and seek protection in Europe. In 2015 alone, the EU registered 1.25 million first-time asylum applicants. The unprecedented influx of migrants overhauled the Dublin rules, which stipulate that countries of first-arrival are responsible for examining asylum applications submitted by people seeking international protection under the Geneva Convention and the EU Qualification Directive.

In the face of Europe’s most severe migratory challenge since the Second World War, the EU finally sought to reform the Dublin rules on asylum to cope with regular and irregular immigration. So far, member states have failed to agree on any distribution mechanism or common measures that ensure border security while effectively protecting the basic rights of asylum seekers and refugees. Initiatives like the EU Trust for Africa and the Migration Partnership Framework presented quick fixes – border control and security to restrict migratory flows – but long-term structural policies to generate stability in countries of origin are yet to surface.

Despite the reduced number of migrants entering Europe, the revised Dublin rules and the Migration Partnership Framework failed to end the humanitarian catastrophe at the EU’s external borders. More than 100,000 migrants still set out the perilous Mediterranean migration route every year. The ineffective European asylum initiatives and the rather slow pace of Greek authorities processing asylum applications cause not only inhumane conditions in refugee camps, but also exacerbate social tensions and strain Greece’s fraying economy. The current situation at the EU’s external borders points towards a perennial mismatch between EU rhetoric and its member states’ actions. While Migration Commissioner Ylva Johansson stressed that the right of individuals to apply for asylum could not be suspended, Greek government spokesman Stelios Petsas defended the Greek suspension of asylum law application as a reasonable response to asymmetrical and hybrid attacks coming from a foreign country.

Make it or Break it – The EU Asylum System

The EU migration policy is an awkward moral clash with its professed values of protecting human rights, individual dignity, and the right to seek asylum under international law – which Greece says it has suspended for now. While EU officials are not tiring of calling for mandatory solidarity mechanisms, none of the rhetoric has succeeded in improving the humanitarian situation at the border and in detention camps. In fact, none of the points agreed upon in the EU-Turkey statement were fulfilled – except the money.

The EU must finally implement effective policies to end the current humanitarian crises on either side of the Mediterranean Sea. This might be the last opportunity to demonstrate that the EU can accommodate people fleeing conflict and persecution, putting their dignity over money and individual European security. Make it or break it – four guidelines can help to manifest a humanitarian asylum system that effectively responds to the current humanitarian crisis at the EU’s external borders.

First and foremost, the EU must immediately end any deployment of warships pushing back small boats that carry refugees. Life-threatening violence renders every humanitarian approach void.

Second, the European Asylum System must guarantee basic rights of refugees and migrants. The most vulnerable people must be resettled from camps such as “black site” to facilities that provide shelter, food, and medical care. As long as Europe does not have a viable asylum system, states that are ready to accept refugees must quickly do so to help people at the border in dire need of humanitarian aid.

Third, the European Union must abandon the malfunctioning logic of deportation and resettlement that is reflected in the EU-Turkey agreement. Instead, asylum procedures must be guided by the rights of refugees and the needs of the most vulnerable.

Finally, the Dublin rules must be reformed to a coherent European asylum system that is based on greater responsibility-sharing among EU states and the humane treatment of all refugees. The reality is, there is no easy way out. Humanity is not for sale.

Dominik Rehbaum is a 2021 Master International Affairs candidate at the Hertie School of Governance and writes about Global Politics and European Defence and Security Policy. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in European Studies of Maastricht University with a focus on European Law and International Relations.