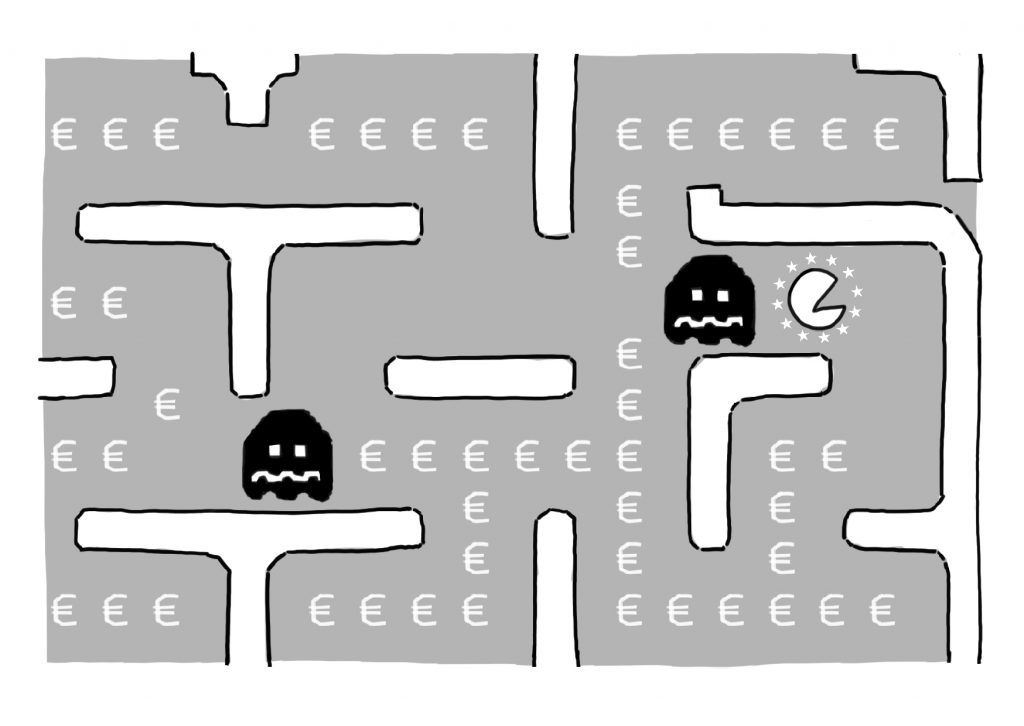

Born-digitals, like Facebook and Google, are fooling Europe’s policymakers at their own game, as loopholes in the outdated European labyrinth of taxation have turned the hunters into the hunted. The century-old EU rules in place for generations of brick-and-mortar players are bending and succumbing to a new species of businesses: digital giants. Without a unified approach, digital giants remain untamed, roaming from country to country and depriving Europeans of their deserved disbursements. A proposal emerging at OECD-level has the potential of changing the rules of the game sustainably.

“Nobody raises the issue of tax avoidance and the rich are not paying their share. It is like going to a firefighters’ conference and no one is talking about water,” the Dutch economist Rutger Bregman sharply criticized the world leaders for their superficial debate at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos. The devastating effects of tax evasion are limited not only to a practical dimension. Citizens and states are defrauded of their revenue used for upholding the European welfare states. Tax evasion also incorporates a moral component, as it destroys the very principles of equality, transparency, and corporate responsibility. One industry particularly infamous for only paying a fragment of its fair share is the digital economy.

Many EU countries struggle with each other for the grace of digital giants by lowering their taxes to a bare minimum. The most prominent example of such behaviour serves Ireland: In 2018, the island nation had a corporate tax rate of just 12,5% compared to the European average of 21,9%, drawing in Facebook, Google, and Airbnb. This tax competition yields large businesses with considerable bargaining power, as they are courted by fellow member states to leave and resettle. An international response by political leaders is needed to “establish a modern, fair and efficient taxation standard for the digital economy” and to tilt the balance of power back in favour of the European member states.

Why is it in the first place that the EU’s existing tax system does not properly target digital companies? The answer seems to lie at the very core of their business models, as the present system taxes companies only in the country of permanent establishment. While this model works for the brick-and-mortar businesses, it ignores the value creation of the digital economy. Through a combination of algorithms, user data, and sales functions, companies have elevated the very idea of value creation into its next evolutionary stage. Taxation, however, has not yet adapted to its new digital targets.

The profits made from a simple user ‘Like’ serve as an example of this evolutionary misfit: Let’s say a German user shares her interests for a certain topic on Facebook, the company creates a user profile and subsequently sells the insights to a third party. Even though the digital raw resource was harvested in Germany, Facebook will still only be taxed in its country of residence, Ireland. The root cause of the inherent mismatch – between where value is created and where taxes are paid – can, therefore, be traced back to the principle of permanent establishment.

The mismatch overextends to a distortion between how much value is created and how much taxes are paid. Digital businesses bore a tax rate of 9.5% in 2018, less than half of the rate of 23.2% levied on traditional businesses. Further, they constitute one of the fastest growing industries. A 2015 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) notes that the line between the digital and the traditional economy is blurring with the former overtaking the latter one. With this trend likely to accelerate, it is improbable that a system designed to tax mostly traditional goods and services will yield the Member States with the revenues they need to uphold the social welfare system. Pierre Moscovici, former EU Commissioner for Economic Affairs, points out that the current system “represents an ever-bigger black hole for Member States, because the tax base erodes.”

Without tax reform, states will experience yawning gaps in their household budgets, making the taxation of the digital economy one of the most pressing economic problems of our time. It is estimated that tax avoidance tactics of multinational companies account for a loss of $100-240 billion in tax revenue globally. The European Commission had proposed a digital tax; however, the proposal failed in March 2019, due to opposition from Ireland, Denmark, and Sweden. Instead, EU finance ministers agreed to outsource their disagreements and keep working on the global tax reform prepared by the OECD.

Since 2012, the OECD had effectively assumed a leading role in taxation issues, when the G20 tasked it with an action plan for adapting the international tax system to the pressing challenges of our times. Within its Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), the organization is currently hosting negotiations with over 130 countries that aim to develop a respective proposal. The legitimacy of the OECD in developing global taxation principles and the inclusive nature for developing countries is rightfully challenged by numerous NGOs. However, it is important to note that the long-term proposal addresses crucial aspects necessary for eliminating tax evasion.

The proposal has two critical pillars focusing on 1) the tax challenges of the digital economy and 2) tax avoidance through a global minimum tax. Pillar One is nothing less than a partial departure from the ‘permanent-establishment’-principle and, thus, an expansion of taxation rights of market jurisdictions – the markets where the “Like” is made. Put simply, this entails allocating a portion of a business’ residual profits from the country of residence to market jurisdictions, where it can then subsequently be taxed. If implemented, the proposal will have far-reaching implications for the entire international tax system. It would restructure the system’s very core: the evolutionary misfit of where profits are created and where they are taxed. According to several experts, the OECD-negotiations set for the magic 2020 deadline are proceeding well – an evaluation attributed to the urgency of the issue.

Despite these ongoing multilateral negotiations, national proposals have emerged. Most prominently, France and the UK enacted their digital service taxes (DST) at 3% and 2%, respectively. The US did not welcome these proposals: According to Trump, such taxes constitute a direct attack on American corporations. In a riposte, he threatened France, which is seen as a pioneer of digital tax reforms, to impose tariffs on champagne, cheese, and handbags. At the 2020 WEF, French President Emmanuel Macron and Donald Trump, however, agreed that the unilateral tax plans would be postponed for one year to find a solution at the OECD-level. Nevertheless, several other European OECD countries (Figure 1) have suggested similar taxes while differing in maturity and content.

DSTs, however, are designed rather as a “quick fix”. They do not shake the foundation of the permanent establishment, which is the necessary shift to adopt the international taxation system to the digital environment. Hence, it is questionable whether unilateral short-term approaches are the right way to encounter the truly global issue of the digital economy’s taxation.

Even though Margrethe Vestager, Europe’s “tax lady”, rightfully maintained that it is “very important that we keep up the momentum”, unilateral solutions run the risk of producing a patchwork of incompatible regulations. At a G20-meeting in February 2020, OECD Secretary-General Ángel Gurría demanded: “Stop a mess, stop a cacophony of unilateral measures”. National digital taxes would inevitably lead to tensions in trade and could have a devastating impact on the global economy.

The six countries that have pressed forward with implementation , have all stated that they would repeal their national proposals once an OECD-agreement is reached. There are strong reasons for doubt. The French DST, for instance, does not include an exit clause.

Using the existing tax system, digital giants openly continue to outsmart policymakers.. At the 2020 Munich Security Conference, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg asserted that he was “happy to pay more tax in Europe”; however, who is Mark Zuckerberg to decide how much tax he wants to pay? This choice cannot be left to companies.

With the base of policy efforts at the OECD-level, the EU can hold the digital economy to its fair share of responsibility in the global taxation system. The EU has set a global benchmark with the General Data Protection Regulation to safeguard the privacy of its citizens. Why not also champion the taxation of the digital economy? No less than the future of the European social welfare states depends on it.

Wiebke Dorfs is Editor for the Economics and Finance section of the Governance Post and a 2021 Master’s of International Affairs candidate at the Hertie School. Being raised in France and Germany, she completed her Bachelor in International Business at Maastricht University with a focus on development economics and financial markets. Before joining the Hertie community, Wiebke has worked for a political consultancy in Berlin and an MEP in the European Parliament. She is particularly interested in the interface of economics and sustainability (i.e. sustainable finance and the circular economy), feminism and late afternoon brunching.