Aurat March – Urdu for ‘Women’s March’ – is an annual demonstration held on March 8th in the Pakistani cities of Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad. Women, non-binary people, the LGBTQIA+ community, and cis male allies from diverse backgrounds come together in solidarity with the global #MeToo movement and protest against the patriarchal repression of their basic rights. Aurat March is an independent movement, debuted in 2018 and facilitated by local feminist collectives all over Pakistan. The lead-up to this year’s march was marred by petitions to declare it as an anti-state and anti-Islamic activity.

Voices Against Freedom

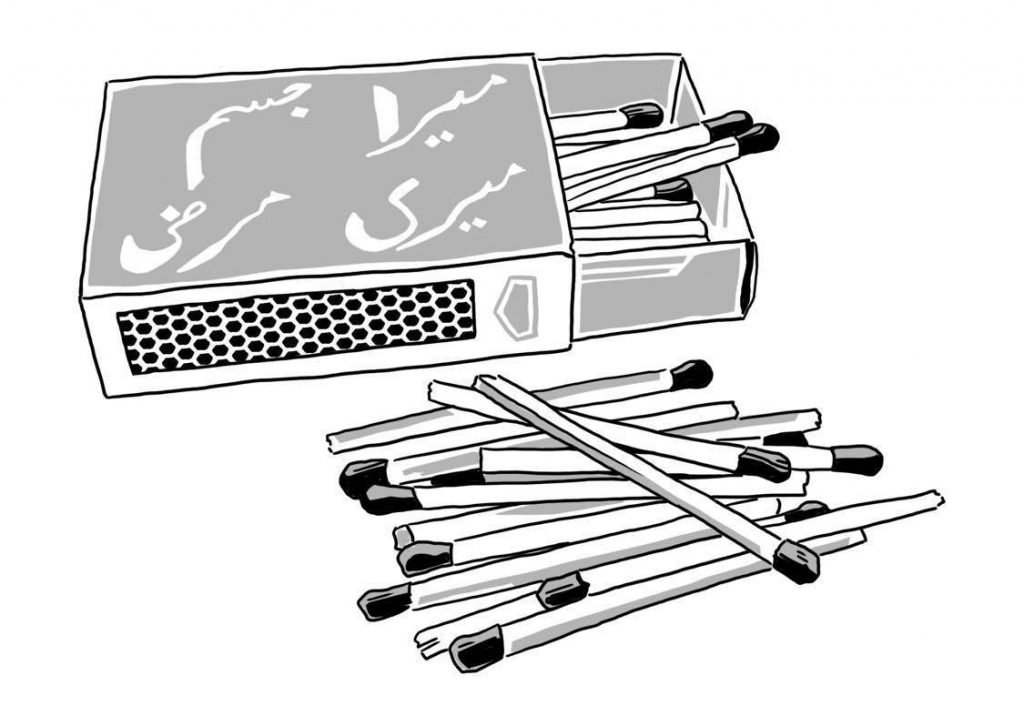

On a Sunday morning in the sprawling city of Lahore, hundreds of women, men, and children gathered in the scorching heat to demand basic human rights. Attendees passed through body scanners amid a tight police presence. While one group of spirited college girls chanted slogans like “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” (My body My Choice) and “Apna Khana Khud Garam Karo” (Heat Your Own Food), another group of doughty women walked in a silent group wearing masks bearing the face of Qandeel Baloch, a social media sensation who became a victim of the atrocious practice of honour killing. A blood-red banner stretched across the middle of the crowd, with stories of violence inscribed on it. Curious onlookers with confounded expressions clicked pictures, looking on from rooftops and along sidewalks at the marching women. The crowd was dotted with a palette of colourful posters with themes ranging from reproductive rights and underage marriages to demands for equal pay and justice.

Previous Aurat Marches received severe criticism and backlash from conservative and religious circles. Feminist activists, organisers, and participants of the Aurat March received rape, acid attack, and death threats on social media. Male celebrities and politicians publicly abused activists while criticising slogans on national television. Feminism, in their opinion, endangers Pakistani society and culture. The majority of conservative, religious segments have declared the problems highlighted by marchers as “non issues” and rejected them as ploys to “westernize” society. They assert that feminist women should talk about “real” issues, such as the worsening economic situation of the country, instead of holding “obscene and vulgar” posters. Islam, according to them, has given all rights to women. This backlash against Aurat March and feminist activists raises concerns about the situation and the status of minorities in Pakistan.

The 2020 Aurat March was marked by a feeling of apprehension and fear due to the extreme backlash emanating from religious and conservative circles. Stringent security measures and police presence painted a risky picture of the peaceful march for basic human rights. Religious parties announced a counter “Chastity Rally” on March 8th in the capital city, Islamabad. Members of this counter rally broke through the barrier separating the neighbouring Aurat March and pelted the peaceful marchers with bricks and stones. Although only minor injuries were reported, this atmosphere of fear and violence to suppress the voices of repressed minorities is an alarming prospect.

Being a Woman in Pakistan

The status and situation of women in Pakistan varies according to the socio-economic class that they come from and the region they live in. A minority of upper middle-class urban women have access to higher education and pursue careers that can move beyond traditional roles. But the reality for the majority of working class women in rural areas is different due to poverty, violence, traditional gender roles that are enforced on them, and the lack of access to education. According to a Thomson Reuters Foundation’s poll conducted in 2018, Pakistan remained the world’s sixth most dangerous country for women due to regressive cultural traditions, sexual violence, domestic servitude, discrimination based on property and inheritance rights, access to education, and nutrition. The maternal mortality rate in Pakistan is among the worst in the world and life expectancy for women is lower than that for men. Religious minorities are under attack due to increased intolerance, and young girls, mainly Christians and Hindus, are forced to marry Muslim men.

No Country For Women

In the 80s, military dictator General Zia suspended all fundamental human rights guaranteed in the Constitution of Pakistan. He introduced a series of repressive laws to tarnish women’s status, eliminate and restrict their personal liberty, visibility, and participation in public life. The Qanun-e-Shahadat Order damaged the status of women by making the testimony of a woman equal to only half the weights of a man’s. The Hudood Ordinances eliminated the difference between rape and adultery and made fornication a crime. This law treated any report of rape as a confession of adultery by the victim and held them accountable. It also dictated women’s clothing, perpetuated domestic violence, and reduced the role of a woman to a slave who cooks, cleans, and produces a male heir. This period of Pakistan’s turbulent history was characterized by public floggings of women and police brutality against activists.

The Origins of Feminist Movements in Pakistan

The first wave of feminism in Pakistan dates back to the creation of the country in 1947. During this time, privileged women from upper class families spearheaded the movement, but their focus was limited to social welfare, rehabilitation of refugees and underprivileged people, along with education of children and young women. They did not contest dictatorships, religious and cultural norms, and stayed away from overtly political positions. The second phase of feminism, led by urban WAF (Women’s Action Forum) and rural Sindhiani Tehreek, challenged the military dictatorship, religious decrees, and General Zia’s draconian legal regime and fought for a democratic, secular, and equal state free of patriarchy and feudalism. These women took to the streets and struggled for the restoration of the status of women in the public sphere, but they did not engage in body politics and other matters that regulate the private lives of women. Despite being beaten, jailed, threatened, and labelled as blasphemers and foreign agents, these women succeeded and got rid of the majority of Hudood Ordinances.

Feminism Today

The new wave of feminism builds upon previous movements, in terms of objections against fundamentalism, militarism, and the desire for equality and democracy, and drives these home with the addition of open rejection of gender roles and conservative and regressive religious and cultural obligations imposed on women. These young feminists and their movement are inclusive, diverse, and intersectional. They are reclaiming their bodies, public spaces, denouncing sexual harassment, and asking for an equal distribution of gender roles, access to education, free will, and inheritance rights.

Mera Jism Meri Marzi (My Body My Choice)!

The demands – and perhaps the very existence – of the Aurat March are anathema to existing patriarchal structures. The so-called “indecent and immoral” placards represent a grim reality for the majority of women in Pakistan. Critics can neither stop the marchers nor the movement. We will continue to march with tremendous energy, courage, and passion into an unknown but exciting future. Aurat March brought about mainstream public discourse regarding feminism, and for that, it was a resounding victory even before it happened.

If you would like to know more about, or support Amna’s work, click here.

Amna Riaz is a Helmut Schmidt Scholar at the Hertie School. In her home country Pakistan, she started a movement to socially and economically empower the Khawaja Sira community. She is currently working with LGBT+ refugees and migrants in Berlin.”