Why did Trump’s latest attempt to solve the Israel-Palestine conflict receive the full support of the Israeli government? Georg Weininger, MIA 2020 candidate and former peace consultant for the Willy Brandt Center Jerusalem, argues that the Israeli endorsement of Trump’s ‘Deal of the Century’ should be analysed as an emergency break of state policy. From the Israeli government’s perspective, the establishment of a Palestinian state under very precisely defined conditions can be seen as the only possibility to maintain Israel’s democratic constitution in the long term.

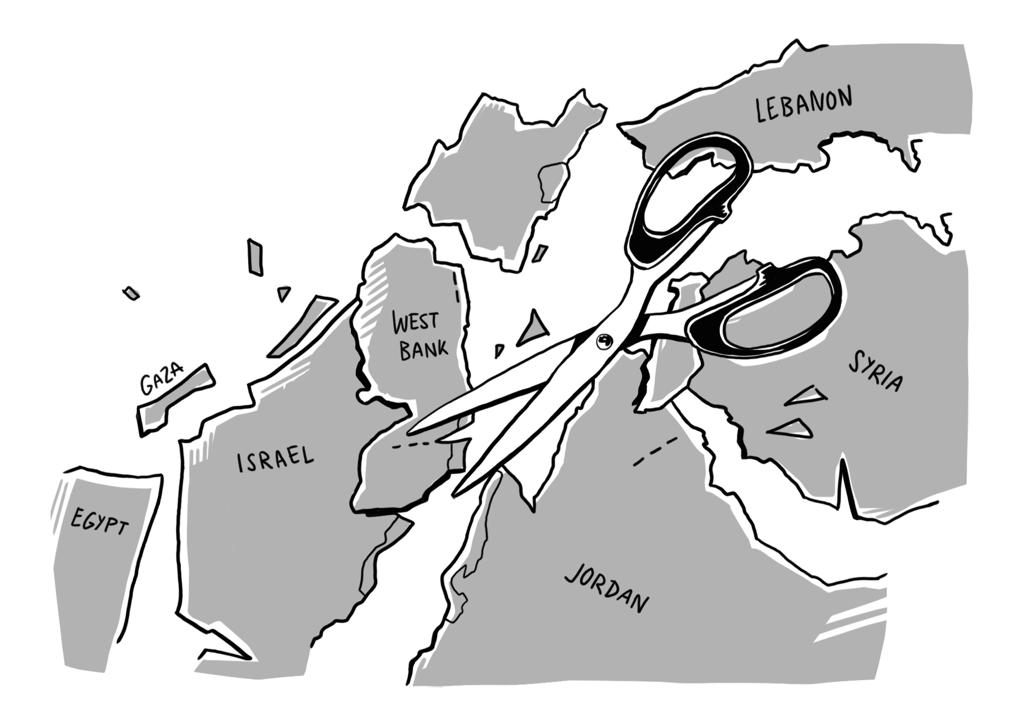

On January 28, US President Donald Trump released his long announced ‘Deal of the Century’ as his solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The 80-page document contains a conceptual map that gives a rough indication of the envisaged division of the Holy Land. The plan was celebrated with the passionate support of Israel’s government but boycotted by the Palestinian political leadership.

It may surprise the casual observer that this Israeli government, which has been always more than reserved about a two-state solution, is now enthusiastic about the prospect of founding a Palestinian state; however, the Israeli endorsement of the Deal- neither surprising nor incoherent – should rather be analysed as an emergency break of state policy.

Two aspects have characterised previous approaches to resolving the conflict over territory between Israelis and Palestinians and decades of mass brutality: They sought to divide the country and they failed.

Yet, according to the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli rejection of division is over. In his statement, held immediately after President Trump’s presentation of the peace and partition plan, he acknowledged that this very layout would possibly allow for a future state for the Palestinians. Netanyahu was one of the protagonists opposing the partition plans in Oslo roughly 20 years ago. His novel approval can only be understood in the context of the historical developments that have led to a political impasse.

In 1967, Israel conquered the West Bank and Gaza, which had previously been under Jordanian and Egyptian administration since the end of the British Mandate in 1948. In both areas, permanent Jewish settlements were subsequently built. Historically, the development of these civilian settlements has been linked to Israel’s security as their presence was considered a strategic measure against further military attacks from adjacent countries. Later on, Jewish Israelis moved to the occupied territories for different reasons. They did and continue to do so on national or religious grounds or simply for economic reasons since housing in these settlements is often subsidized; however, as a consequence of the second Intifada (2000-2005), Israeli decision-makers drafted a new security strategy.

In the Gaza Strip, Jewish settlements were unilaterally dismantled by Israel. In the West Bank, on the contrary, the permanent settlement pattern as started in 1967 grew steadily. This development is flanked by a complex network of military posts, movement restrictions, and separated infrastructure. The territories captured by Israel in 1967, including the eastern parts of Jerusalem, provide today living space for well over half a million Israelis. Throughout governments of all political colours, Israel has made clear that it does not intend to clear the West Bank as it has in the case of Gaza. In fact, the opposite is true.

After more than 50 years of settlement activity, only a few contiguous areas on the West Bank have remained without Israeli settlements. Even if one assumes that the idea of a withdrawal of now about 600,000 people would be physically feasible, there can no longer be a political majority in the country for it. Simply giving up on it, as in the Gaza-case, is therefore not an option; however, what was initiated for security reasons and continued by various groups with different motives has left one question unanswered: If the claim is made and realised to settle in the occupied territories, what status do the Palestinians have in the same area?

In order to understand the scope of this question, we must look at the ethnic composition of the Israeli nation. The country currently comprises about 20% Arab citizens–Palestinians. In democratic decision-making, this is already problematic. Since most Jewish Israeli parties exclude the Arab parties as coalition partners, Israel’s already very fragmented political landscape offers even less room for maneuver in forming a government; This is one reason why in the recent past there has been almost non-stop voting in the country, but a government majority could never be established. Simply annexing the West Bank and granting its Palestinian population Israeli citizenship is not an option. The resulting even larger Arab population share would indeed jeopardise the Jewish majority in the country and thus undermine the founding idea of Israel as a Jewish state.

Israel thus faces a trilemma. A Jewish majority in the country, democracy and the annexation of the West Bank are three state policy goals, of which at any given point only two can be brought into harmony while the third will inevitably be excluded. Trump’s plan offers the prospect of establishing a sovereign state for the Palestinians, largely without the need to abandon Israeli settlements. The areas, separated by the latter but intended to be Palestinian territories, shall be linked by bridges or tunnels.

Jared Kushner, son-in-law of the US president and alleged architect of the ‘Deal of the Century’, told Al Jazeera that the draft is to be understood as the last chance for the Palestinians to get their own state. It is the prospect of a state on partially contiguous territory only without control of its external border, without Jerusalem as the capital and without a right of return for the refugees.

Kushner did not specify what Palestinians could expect if they do not accept the offer. Yet, the unclear nature of the consequences of noncompliance is the truly burning question. Viewed dispassionately, time is much less pressing for the Palestinians because under these conditions, it is very little for them to lose. From Israel’s perspective, however, Kushner’s alarmism is more understandable. Given the trilemma outlined above, democracy itself is at stake for Israel in the current situation.

From June 2015 to December 2017, Georg worked as a peace consultant for the Willy Brandt Center Jerusalem. As a project manager, he facilitated educational cooperation between youth movements from Israel and Palestine. He worked with youth associations with a focus on political education, encounter work, and international partnership.