Women’s rights are often used as means to an end, instrumentalised for political, cultural, religious and economic purposes beyond the advancement of justice. MIA student Pernilla Söderberg sheds light on how the unresolved issue of World War II sex slaves plays a crucial part in the construction of national identities in two East Asian countries today, and explains why international commemorations aren’t helping.

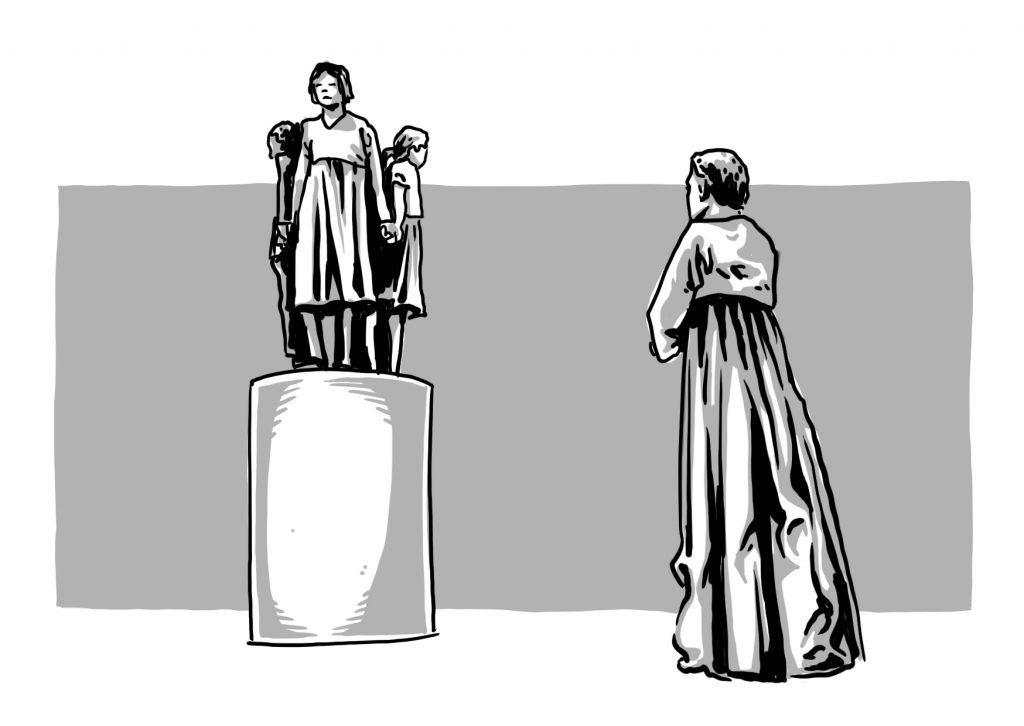

Sixty-five years after the end of World War II, international civil society organisations started erecting memorials to commemorate the ‘comfort women’. Today, there are about fifty memorials around the globe, including nine in the United States. Although the international commemoration is commonly argued to raise awareness of conflict-related sexual violence, it does little to bring justice to the ‘comfort women’ themselves. Au contraire. From a perspective of ethics of memory, remembering the ‘comfort women’ is the duty of South Korea and Japan, not the international community’s. By spreading one side of a two-sided story, international civil society organisations are further antagonising the countries and impeding their ability to accurately remember.

The story of the comfort women memorial statue began in 2011 when a small bronze figure, depicting a barefoot Korean girl sitting in a chair, went up in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. The story of the ‘comfort women’, however, started long before that. ‘Comfort women’ is the euphemism for the rather uncomfortable term ‘sex slaves’ and refers to the many, yet unknown number of, women and girls who were recruited to provide sexual services to the Japanese military before and during World War II. The majority of women came from the Korean Peninsula, but also from China, Taiwan, and parts of Southeast Asia.

The fate of the ‘comfort women’ remained untold for decades, as the victims lived in silence. When they started to share their stories and demand justice in the early 1990s, it came to be the beginning of a long and nasty battle over national narratives. Today, almost thirty years later, the ‘comfort women’ issue lies at the heart of the tense relations between South Korea and Japan. Who is guilty, and of what, continues to be contested and, while the Japanese government is taking measures to forget, the South Korean government desperately wants to remember.

Both countries, however, are rewriting the past, controlling their respective collective memories, and protecting their national pride and innocence. This is because, as philosopher Avishai Margalit wrote, “in the disenchanted world of critical history, there is no backward causality”, or put simply, neither South Korea nor Japan can go back in time and undo the past. They can only redo how it is remembered.

And that is exactly what they are doing.

For South Korea, the ‘comfort women’ serve as a symbol of a victimised and humiliated nation. And the only way to hold Japan responsible is by maintaining the idea of pure and innocent girls bedraggled by a Japanese evil. Such a uniform picture cannot fully explain who the ‘comfort women’ were, but any contradicting narrative is met with South Korean hostility.

In 2013, Park Yu-ha, a professor of Japanese literature at Seoul’s Sejong University, published the book Comfort Women of the Empire, in which she provided a more comprehensive picture of history. Many of the ‘comfort women’ were, indeed, forcibly abducted, but some joined voluntarily. Some were sold by their own families or recruited by other South Korean men. Others were not sex slaves, but prostitutes. A number of South Korean women even fell in love with the Japanese men, thereby not only sleeping with the enemy but also loving them. In response to the book, the South Korean government ordered Professor Park Yu-ha to redact 34 passages and a Korean court mandated that she pay 10 million won (USD 8,800) to nine of the ‘comfort women’ still alive.

The Japanese government, on the other hand, has denied the existence of ‘comfort stations’ and ‘comfort women’ for decades. As more and more women began speaking out, and the government was confronted with proof of the links between itself and the ‘comfort stations’, it could no longer keep the issue shut. It began to recognise its involvement in the ‘comfort women’ system and, in 2015, announced it would give reparations to the surviving South Korean ‘comfort women’.

Although Japan has taken some responsibility for the ‘comfort women’, the country has taken a step backwards with a turn to the political right in the 21st century. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is associated with a revisionist agenda of whitewashing Japan’s past, denouncing and undermining the country’s earlier statements of responsibility.

Yet, the point of the matter is not who is right and who is wrong. In all likelihood, they are both partially wrong. The point is that the memory of the ‘comfort women’ is used by both countries to tell a one-sided story of national identity. This is how antagonistic identities work. The one cannot survive without the other, and so the idea of the innocent and humiliated South Korea cannot exist without the notion of the evil imperialistic Japan, and vice versa.

In this process, however, remembering the victims is lost. Yet, it is the duty of both Japan and South Korea to do so. Japan needs to remember the harm it caused, and South Korea must not forget that some of that harm was inflicted by itself. It is not a question of concealing Japanese history. No, there is little doubt that Japan’s colonialism facilitated the ‘comfort women’ system and that this historical burden must be integrated into the Japanese collective memory. But in order to do so, South Korea also needs to remember its own, not so one-sided, past. Doing the opposite, that is, continuing to use the memory of the ‘comfort women’ to facilitate nationalistic agendas, will only further the comfort women’s exploitation.

And herein lies the crux of the problem. By spreading the memorial of the innocent and young comfort woman around the globe, civil society organizations are disseminating the memory of an innocent and humiliated South Korea, perhaps legitimising it. This feeds into a polarising spiral of national narratives and identities, in which South Korean guilt is hidden and Japanese responsibility highlighted. To such a description of history, Japan can only respond with further denialism. In response to that, South Korea will continue to paint a portrait of its own innocence. In this manner, civil society organizations are hindering both countries in remembering what they so desperately need to recollect. Therefore, the international commemoration needs to stop. For the victims. And for the ethics of memory.

Pernilla Söderberg is a 2019 Masters of International Affairs candidate at the Hertie School of Governance. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Stockholm University where she specialized in issues related to gender (in)equality and global justice. Pernilla is fascinated by the role of language in shaping social realities and loves all things creative.

Pernilla Söderberg is a 2019 Masters of International Affairs candidate at the Hertie School of Governance. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Stockholm University where she specialized in issues related to gender (in)equality and global justice. Pernilla is fascinated by the role of language in shaping social realities and loves all things creative.