Gun control legislation has a prominent place in US political discourse, falling in and out of fashion as high-profile shootings occur. But how much do we actually know about gun sales, or interest in gun ownership for that matter? This article leverages web search data to complement the official statistics and examine the changing public perception of guns in times of gun violence.

Gun control has been a re-occurring issue in the political discourse of the United States. According to a study from USA Today, there have been 272 mass shootings in the US between 2006 and 2017, defined as an incident where 4 or more people were killed (approximately one incident every two weeks). It seems that each time a mass shooting occurs public debate over gun control is revived, but after several weeks the issue is virtually forgotten and no concrete changes are made to public policy.

While interest in gun control legislation increases during the days after a shooting, so does interest in buying a gun. In the wake of high profile mass shootings, stocks in gun manufacturing companies like American Outdoor Brands (the parent company of Smith & Wesson) and Sturm Ruger rise, as do the number of background checks submitted to the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). Speculations about the causes behind this phenomenon are wide-ranging. On one hand, this could be a reaction from gun enthusiasts who seek to build up a stockpile while regulations remain the same. On the other, this could represent additional interest from non-owners who seek to arm themselves against future violence.

Interestingly, gun sales are a difficult issue to study as there is no official record kept. The best measure of gun sales is provided by the background checks that are submitted to NICS as part of the gun-purchase procedure. This is a step that all federally-licensed gun distributors must undertake for each customer, though this is not required for unlicensed distributors or private sales in many states. Thus, this estimation presents an incomplete picture of gun sales and general interest in buying a gun.

Some academics have explored the use of web search data as a proxy variable that captures trends not available in official statistics. One example of this, a 2015 study by Alex Street and co-authors, leverages Google search frequencies to estimate the interest in voter registration in the United States federal elections after the state registration deadline. Examining the search frequencies for the term “register to vote” before and after the state imposed deadlines, they fit a model to predict the number of voters who would have registered to vote in the post-deadline period if this option was available.

I think a similar method could be used to investigate gun sales. Granted, a simple Google search does not guarantee the purchase of a weapon, or that this purchase would be background-check exempt and missing from official statistics. However, I believe that comparing search frequencies to background checks could indicate the additional interest in purchasing a gun that is not captured by the official statistics. Moreover, this metric probably represents a different demographic from those who appear in the background search data. A gun enthusiast is most likely familiar with the purchase procedure and points of sale in their vicinity, so people conducting a Google search for “buy a gun” are probably non-gun owners looking into the process or people specifically trying to bypass the background check criteria.

For my analysis, I chose to look at the search frequency of the phrase “buy a gun” because it is both clear and concise, and I think it indicates more intent to purchase than other phrases. The phrases “how to buy a gun” or “gun regulations in [state]” might be more searched by people interested in finding out about gun control but not necessarily looking to buy a weapon. Other terms like “gun shop” might indicate intent to buy, but there is more likelihood that this sale will be accompanied by a background check.

The data on the search frequency for Google search terms can be accessed via the Google Analytics platform. The search data is reported on a relative scale, presenting the popularity of a search term in relation to its most popular period (a range between 0 and 100, where 100 is the month when the term was searched most). I compared this to the number of background checks submitted to the NICS, which is made publically available by the FBI. Since the NICS presents aggregate statistics, I convert this to a relative scale to facilitate the comparison between the two metrics. The figure below shows the relative number of background requests submitted to the NICS and the relative search frequency for ‘buy a gun’ between January 2006 and April 2018.

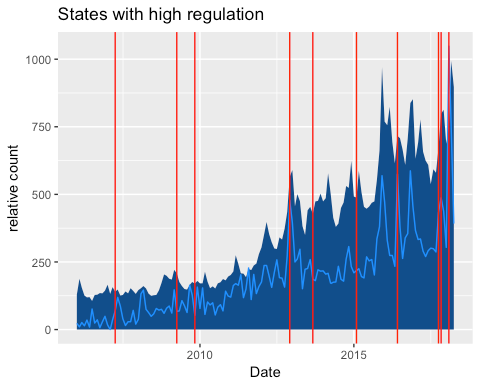

The graph above presents the data for states which require a background check for all gun sales. The dark blue area represents the relative number of background checks submitted, while the light blue line indicates the relative popularity of the search term “buy a gun”. The vertical red lines indicate the ten deadliest mass shootings in the US during this period. If Google searches for “buy a gun” do in fact capture a proportion of private gun sales, I would expect the Google search popularity to closely follow fluctuations in the number of background checks in the states where all gun sales are accompanied by a background check.

The graph above presents the data for states which require a background check for all gun sales. The dark blue area represents the relative number of background checks submitted, while the light blue line indicates the relative popularity of the search term “buy a gun”. The vertical red lines indicate the ten deadliest mass shootings in the US during this period. If Google searches for “buy a gun” do in fact capture a proportion of private gun sales, I would expect the Google search popularity to closely follow fluctuations in the number of background checks in the states where all gun sales are accompanied by a background check.

There is an increasing trend across this period which can partially be explained by the increasing number of states which have passed gun control legislation. Many of the predominant peaks in the Google search popularity align with these high-casualty mass shootings. For example, a peak occurs in both variables after February 2018, the month of the school shooting in Parkland, Florida. Another prominent peak occurs in December 2015, the month of the mass shooting in San Bernardino, California. It should be noted, however, that high-profile shootings are not the only events that motivate interest in buying a gun. One peak in the data occurs in November and December 2016, when no highly publicized mass shootings took place. It does coincide, however, with the election of Donald Trump as president, which may reflect an emboldened American public attitude towards guns.

Overall, a visual inspection of the trends in these two variables seems to indicate that the peaks and valleys mirror each other fairly consistently, especially in more recent years. This could be an indication that the interest in buying a gun through private or unlicensed distributors online is represented in the search frequency for this term, and reflected in the background search statistics.

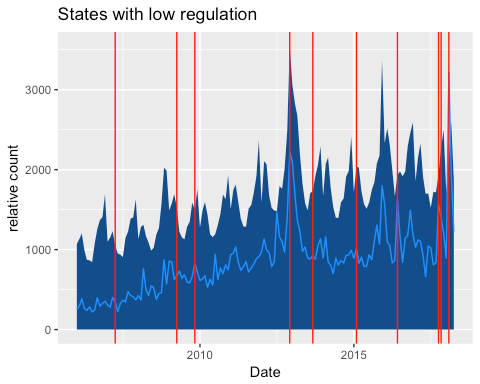

This second plot shows the same data for states which do not require a background check for private sales through unlicensed distributors. The aggregate search frequency and background checks are a lot higher because there are a lot more states with low regulations. There is also a pretty evident cyclical pattern in the relative number of background checks, with regular spikes in December each year. Some articles link this spike in popularity to the Christmas season, as guns are often exchanged as a gift during the holiday season. During the summer months the number of background checks dips to a low, possibly due to the fact that hunting is out of season in most states for most species.

This second plot shows the same data for states which do not require a background check for private sales through unlicensed distributors. The aggregate search frequency and background checks are a lot higher because there are a lot more states with low regulations. There is also a pretty evident cyclical pattern in the relative number of background checks, with regular spikes in December each year. Some articles link this spike in popularity to the Christmas season, as guns are often exchanged as a gift during the holiday season. During the summer months the number of background checks dips to a low, possibly due to the fact that hunting is out of season in most states for most species.

Visually, there appears to be less variation in the search popularity (it doesn’t mirror the cyclical nature of the background checks), though many peaks in both sources line up with high profile shootings. Possibly, this divergence between trends in search frequency and background checks is driven by gun enthusiasts who would not do a Google search before going to purchase a gun. There are, however, several points where a decrease in background checks coincides with an increase in search term popularity, which may be the indication of an increase in private sales that aren’t reflected in the official background check data. For instance, this occurs in July 2012 – the same month as a shooting in a movie theatre in Aurora, Colorado. Another example of a big discrepancy in trend between search frequency and background checks happens in June 2016, the month of a shooting at a club in Orlando, Florida.

All in all, there is ample space for further refinement in the empirics of this methodology, but I think examining the relationship between Google search frequencies and background checks reveals some interesting dynamics surrounding gun sales and interest in gun ownership in the United States. While complementing national statistics may be one outcome of this study, I believe there are broader implications for policy makers. When the next mass shooting occurs, and unfortunately it will, web search data has the potential to identify the areas most incensed by the violence and targeted campaigns could be deployed to address the causes of increased interest in gun ownership. Targeting these populations with more accurate information about gun violence and gun control legislation may be a key step in de-escalating the discourse around gun control and introducing sensible restrictions on gun purchases.

Bentley Schieckoff  is a recent graduate of the dual Master’s of Public Policy degree between the Hertie School of Governance and Sciences Po Paris. He previously graduated with a Bachelor’s of Social Science from the University of Ottawa, and worked for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada in Ottawa.

is a recent graduate of the dual Master’s of Public Policy degree between the Hertie School of Governance and Sciences Po Paris. He previously graduated with a Bachelor’s of Social Science from the University of Ottawa, and worked for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada in Ottawa.