Two of Italy’s prominent politicians, communists-turned-centrists, are now returning to their leftists roots in order to challenge the moderate government that side-lined them, in the latest manifestation of Italian zigzag brand of politics. MIA student Andrea Enrici laments the opportunism that drives politicians to abandon their beliefs.

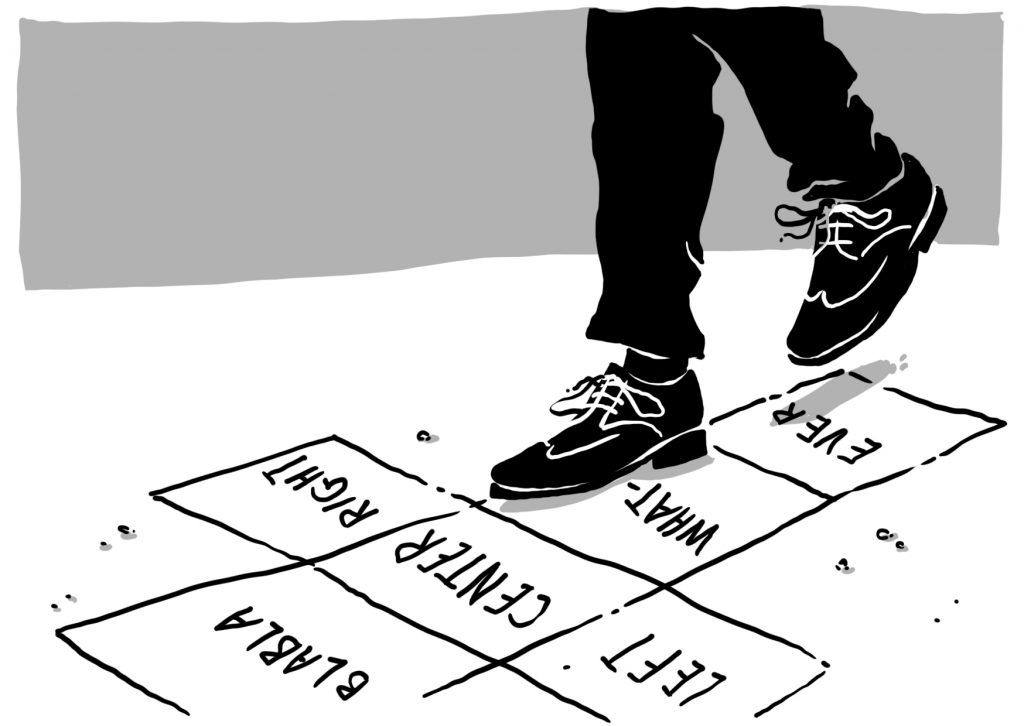

Most Western democracies enjoy party systems based on deep roots and long-standing traditions. In Italy, however, parties are founded and dismantled every few years. The three major groups in the current parliament, for example, have all been formed during the last decade. But new parties never bring about new political ideas: figureheads remain the same, unashamed to radically zigzag between ideologies whenever the repositioning could secure their political survival.

The latest champions of this “transformismo,” as the phenomenon is known, are two respected leaders associated with the centre-left. Back in the 1990s, Massimo D’Alema and Pier Luigi Bersani, who came up through the ranks of the Communist Party, became the Italian referents of Third Way politics, promoting centrism as a means of reconciling right-wing and left-wing politics. While other politicians of that kind, like Tony Blair, Gerhardt Schröder and Bill Clinton, voluntarily left the front lines of politics by the mid-2000s, D’Alema and Bersani were side-lined as a result of Matteo Renzi’s landslide victory as leader of the Democratic Party (PD) in 2013. But they aren’t enjoying their retirement. Instead, they quit the PD last year and recently launched a new left-wing coalition as an alternative to the centrist PD. Neither of them, though, has ever been the Italian equivalent of Jeremy Corbyn and their move isn’t about policies – it’s all about opportunism.

D’Alema was a strong advocate of labour reforms meant to enhance workers’ “mobility and flexibility”. As leader of the post-communist Democratic Party of the Left (PDS), he supported the first comprehensive reform in this field, the so-called “Pacchetto Treu” (1997), which unintentionally paved the way for precarious employment contracts. In 1998, D’Alema succeeded Romano Prodi as prime minister, enlarging the centre-left coalition to include more right-leaning parties. During his tenure, he often butted heads with left-wingers within his coalition, specifically over his support of NATO intervention in the Kosovo crisis.

Bersani held senior positions in centre-left cabinets as Minister for Economic Development (1996-99, 2006-08) and Transport (1999-2001). He supervised many privatisations of state-owned companies, e.g. electricity and telecommunications monopoles, and sponsored at least two waves of “liberalisations”, the Italian euphemism for deregulation. When Silvio Berlusconi’s fourth cabinet collapsed amid the Eurozone crisis, Bersani – then PD leader – gave his full support to the technocratic government led by Mario Monti. Without raising any opposition, Bersani’s party voted in favour of every bill, including a controversial pension reform that postponed retirement age to 67 (the so-called “Riforma Fornero”, 2011), as well as significant cuts to public services.

Last December these former Blairites joined forces with smaller leftist groups to form the “Liberi e Uguali” (“Free and Equal”). They are now prepared to contend in the upcoming general elections with a genuine left-wing platform, including labour and pensions reforms. Inspired by Corbyn’s tactics and crowning as a “rare success story on the left,” I bet they won’t sponsor again the “Pacchetto Treu” nor “Riforma Fornero.” Indeed, Italy desperately needs a new progressive force capable of stopping far-right populists by giving a voice – and real answers – to those who feel left behind, but it is doubtful that D’Alema and Bersani will be the driving forces behind such a movement.

Corbyn has been MP for the Labour Party for over thirty years and stood by his guns also when Blair’s success was at its highest. No one would ever question his intellectual and political coherence. D’Alema and Bersani, on the other hand, cannot claim such qualities: they have been floating towards the centre and back to the left at their convenience. When they lost control of the party they once helped to create, they unceremoniously abandoned it. Moreover, there is no real discord between them and Renzi’s policies: the latter is only following the same centrist path they already took over twenty years ago.

Bersani and D’Alema could learn from the experience of another European politician that tried a similar move in recent history: George Papandreou, Greek Prime Minister at the beginning of the debt crisis that was forced to resign. As new leadership took over his centre-left PASOK, he left his party to create a brand-new Movement of Democratic Socialists. Papandreou’s party, though, only won 2.47% of the votes at the general elections, failing to secure any seats. Last year, eventually, he agreed to form a joint list with PASOK.

Also, the “Liberi e Uguali” was born out of its founders’ insistence to remain relevant, as the only way to preserve their standing for another round. Analysts predicts that the new electoral law will produce a hung parliament: the symbolic threshold of 3% will allow small groups to enter the parliament and become crucial players in future coalition government – a fact that D’Alema and Bersani are hoping to exploit to their advantage.

But even if they manage to clear the 3% bar, they won’t take many votes from the Democratic Party, which stands to lose support because of its own disastrous leadership and controversial policies. Progressive voters won’t be impressed by D’Alema and Bersani’s political rebirth: they will rather give another chance to Renzi to stop Berlusconi’s comeback, or will abstain all together from voting. Those who have been hoping for political innovation, won’t see their prayers answered this time.

Andrea Enrici is a class of 2019 Master of International Affairs candidate at the Hertie School. Italian, he holds a Master of Laws from the University of Pavia. He worked as a legal consultant at UNRoD, a subsidiary organ of the UN General Assembly, and as an international officer at his University. He is keen on politics, history, theatre, art and good books, as well as exploring Berlin’s underground scene or spending long Sundays at the Berghain.

Andrea Enrici is a class of 2019 Master of International Affairs candidate at the Hertie School. Italian, he holds a Master of Laws from the University of Pavia. He worked as a legal consultant at UNRoD, a subsidiary organ of the UN General Assembly, and as an international officer at his University. He is keen on politics, history, theatre, art and good books, as well as exploring Berlin’s underground scene or spending long Sundays at the Berghain.