By resorting to blatantly engineered tactics and fake news prior to the German elections, the AfD demonstrated the lengths to which the far-right is willing to go to garner support. Hertie School Alumni Chris Norman and Angela-Gabrielle Palmer worked together to assist the @DFRLab in researching online content in the final week of campaigning for the German elections. As the year comes to an end, they weigh upon AfD’s efforts to distribute anti-immigration, anti-establishment messages.

Digital tools in political campaigning are increasingly becoming a commonplace feature in elections. Over the past decade, the advent of Web 2.0 platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram have irrevocably altered the way political parties seek to influence the electorate. As the 2017 Bundestagwahl (German Federal Elections) recently demonstrated, the German political scene is no exception to this rule.

In the weeks before the election, the Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab) assembled a team in Berlin to monitor online campaign content. The lab’s goal was to track prominent domestic and international online amplifiers and the interplay between them and other attempts by the far-right’s network to influence German politics. In a short span of time, the distribution of anti-immigration, anti-establishment messages by groups such as Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) increased significantly in Social Media. The AfD’s efforts were frequently assisted by online supporters, many of which were entirely automated and engineered to undermine mainstream political parties. A key example of this was the use of falsified, provocative content developed to enhance the AfD policy platform – what is commonly known as fake news.

Faking It

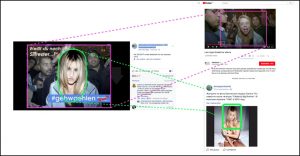

In the final week of campaigning, AfD supporters distributed a campaign image via Facebook alluding to the sexual assaults that took place in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015. The picture shows of a young, white girl surrounded by men of Middle-Eastern origin, and it was accompanied by the slogan: ‘Weiß du noc? Silverste! #gewaehlen’ (Do you remember? New Years’ Eve! #GoVote). As the image was shared by regional divisions of the AfD, the language accompanying it became more inflammatory. The AfD Kreisverband Regensburg (District association) re-posted the image with an appeal to “Schluss mit #Gewalt und #Massenvergewaltigung von Frauen in #Deutschland! Schluss mit “#Willkommenkultur” und links-rot-grünem #Multikulti-Wahn” (End violence and mass rape of women in Germany! No more “#WelcomingCulture” and left, red and green #multicultural madness). The purpose of the image was twofold: to incite xenophobic sentiment and for these views to translate into votes. The image, however, was a fake. It combined footage recorded in Cairo by the CBS journalist Lara Logan during the Arab Spring uprising in February 2011, with that of an FHM Magazine photo-spread featuring the UK model, Danica Thrall.

Left: Screenshot of AfD Hochsauerlandkreis post with a misleading meme (Source: Facebook / Archived). Upper right: Screenshot of CBS News 60 Minutes special with Lara Logan featured on the channels official YouTube page. A subsequent CNN report can also be found here (Source: YouTube). Lower right: Screenshot of WordPress blog attributed to Danica Thrall featuring the FHM photo from which the face close up was taken (Source: Digital Forensic Research Lab / WordPress / Archived). The eyes have been blurred by The Governance Post in order to protect the privacy of the individuals (Germany’s Copyright Law: “Gesetz betreffend das Urheberrecht an Werken der bildenden Künste und der Photographie”)

Fake news is often a combination of a true story and extremely provocative, falsified content. In this case, the original image of an event that occurred six years ago in Egypt was contorted to promote hatred and fear in contemporary Germany. The juxtaposed image was first seen in a post on an anti-Semitic website regarding a “White Genocide”. The picture was intended to appear as a genuine photo-journalistic evidence of the sexual assaults that occurred in Cologne in 2015. The picture was then used by the AfD for its own campaign. Although fake imagery is often relatively easy to spot, as digital technology improves, these images will be more sophisticated and hence, it will be increasingly difficult to determine whether it is fake or not. This will not be confined to images alone, this guide to spotting fake photos predicts that fake video will become another important device in the future.

By resorting to such blatantly engineered tactics immediately prior to the election, the AfD demonstrated the lengths to which the far-right is willing to go to garner support.

Botnets

Over the past few months, the group EinProzent has distributed regular posts accusing both Angela Merkel and the CDU of electoral fraud. In days prior to the election, these efforts increased as overtly partisan groups such as wahlbeobachtung.de (“election observation” in German) asked to volunteer as electoral observers. The combined impact of these groups was the propagation of the idea that incumbent parties would engineer a favourable election outcome. The pamphlet distributed by wahlbeobachtung.de via Facebook warned its followers: Merkel auf die Finger schauen! (Watch Merkel’s fingers).

The overall impact of these posts was relatively contained, as these sentiments were predominantly shared by like-minded groups. However, as @DFRLab detected, the campaign gained further momentum with assistance from automated “bot” accounts coming from a Russian-language botnet. This botnet posted commercial and pornographic messages as well as political content in support of the AfD, in addition to content critical of the Russian anti-corruption campaigner and 2018 Presidential candidate, Alexey Navalny. While it is not possible to establish who is responsible for the botnet, its past content reveals that it caters to a Russian-language audience. Although it is possibly run by an AfD supporter, it is more likely that such a commercial botnet was specifically hired to agitate in their favour. This activity came as no great surprise, as Russia is increasingly suspected of attempts to influence politics that accommodate its own agenda. More importantly, this provides further insight into how Web 2.0 platforms such as Twitter can be utilised to attempt to influence voter behaviour, in particular by spreading misinformation.

Russian Friends

The AfD stands out for its direct appeal to the Spätaussiedler, ethnic Germans from the former USSR repatriated in Germany. This often takes the form of producing campaign materials in Russian and advocating the end to the sanctions regime against the Russian state. In turn, a number of Russian news agencies assisted the AfD and like-minded politicians. RT Deutsch and Sputnik Deutsch actively engaged with candidates on issues concerning the conflict in the Donbas, annexation of Crimea, government sanctions and the welfare of Russians residing in Germany. This provided the AfD an additional media platform that was not available to other mainstream political parties. Although it was not as overt in German as in the US Presidential elections, there is sufficient evidence that indicates concerted efforts by foreign actors.

Another social media platform which frequently invoked messages in favour of the AfD was Vkontakte (VK), a Russian-language alternative to Facebook. With 6.9% of its visitors coming from Germany, VK is currently the 8th most popular website in Germany based on traffic. It outranks Twitter, Der Spiegel, Bild and Whatsapp. @DFRLab paid special attention to the platform’s online traffic, in particular to its popularity amongst AfD supporters. @DFRLab found that up to 90 percent of the most popular posts on VK concerning the German election supported the AfD. The DFRLab found that these users had a strong preference for highly-emotive, biased online media content, most of which were anti-Merkel and anti-migrant. As VK is a Russian social media tool, it effectively bypasses any German legislation on hate speech and discrimination. Accordingly, this provided an ideal portal to disseminate anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim campaign content.

In many respects, the online efforts of the AfD and its network of supporters were enviable. In a relatively short period of time, these voices moved from sitting on the periphery of the German political arena into a position of decisive influence. However, spreading fake news, and using botnets and platforms which skirt German hate speech laws are detrimental to the quality and robustness of democratic institutions and principles. In these conditions, the first victim of electoral politics will inevitably be the truth. As a consequence, governments, political parties and voters must be attuned to the possibility of manipulation by fake news, botnets, and foreign influences.

Angela Palmer is an Executive Master of Public Administration alumni from the Hertie School of Governance. Born in Hobart, Australia, she has spent the last few years living in Melbourne, London, Prague, Sydney and now Berlin. Angela holds degrees from the University of Tasmania and the University of Melbourne, where she studied Political Science and Psychology. Prior to coming to Hertie she worked in the UK Public Sector and Australasian Not For Profit Sector, specialising in Governance and Freedom of Information. Her key areas of interest include post-Communist politics, digitalisation and data security, and political psychology.

Angela Palmer is an Executive Master of Public Administration alumni from the Hertie School of Governance. Born in Hobart, Australia, she has spent the last few years living in Melbourne, London, Prague, Sydney and now Berlin. Angela holds degrees from the University of Tasmania and the University of Melbourne, where she studied Political Science and Psychology. Prior to coming to Hertie she worked in the UK Public Sector and Australasian Not For Profit Sector, specialising in Governance and Freedom of Information. Her key areas of interest include post-Communist politics, digitalisation and data security, and political psychology.

Christopher Norman holds a Master of International Affairs from the Hertie School of Governance and is a board member of the Hertie Energy and Environment Network. He hails from Seattle and has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Linfield College in the United States.

Christopher Norman holds a Master of International Affairs from the Hertie School of Governance and is a board member of the Hertie Energy and Environment Network. He hails from Seattle and has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Linfield College in the United States.