Mark Dawson is Professor of European law and governance at the Hertie School and has been watching the aftermath of the Brexit referendum unfold from Berlin. After the dust settled, Lisa Gow, one of the Executive Editors of the Governance Post and a fellow Scot, met him to shed light on the constitutional and economic futures of the UK, Scotland and the EU.

How did you feel on the day that the Brexit referendum result was announced?

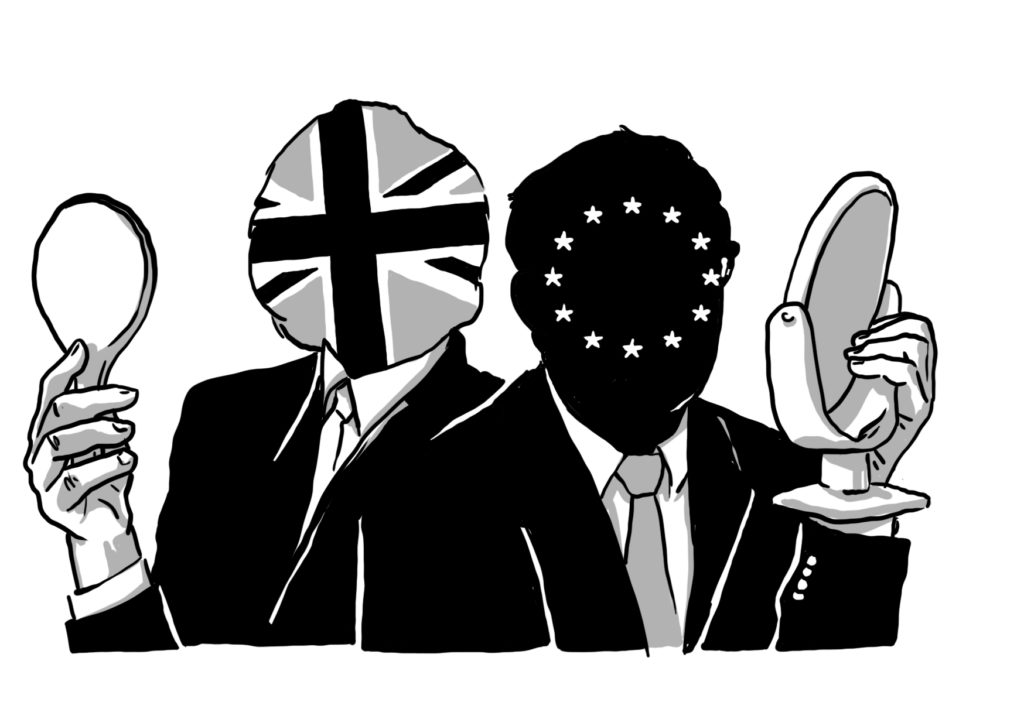

I felt like a lot of British people did, especially those who live and work in Europe. I felt very estranged from my country. I had been aware that feeling European wasn’t as common in the UK as it is amongst myself, my friends and colleagues. On that day, I realised that there was almost an explicit rejection of the notion that being British and European were compatible with each other.

It brought home to me, on a personal level, something I had seen on an intellectual level. I’m part of a group of individuals who are geographically mobile and who benefit from European integration in lots of different ways. However, within all European societies there’s another class of people who don’t benefit, or don’t see themselves as benefiting from integration.

TGP: You’re also Scottish. What role does this play?

As Scots, we’re used to having a nuanced identity. Historically at least, we’re used to being Scottish and British and European – and even Aberdonian, like me! So there’s a kind of interlocking of identities. On the other hand, in England, Englishness and Britishness are conflated. The Scots have felt comfortable with the European project from the beginning. We’ve always been told that we’re a small country, that we can’t make our way in the world without making alliances with others. Historically, we gained access to global trade through the British Empire, after forming a Union with England in 1707. We had to trade off a certain amount of sovereignty to London in order to reap the benefits of the Empire. The concept of a nuanced identity didn’t get through to the English population in the way that it had been accepted for centuries by the Scots.

Do you hope to see an independent Scotland within the EU one day?

Scotland is in a very difficult situation right now. On the one hand, it has a strong historical and economic attachment to Europe. The Scottish economy relies on exports such as oil, gas and whisky, so Scotland clearly needs access to the European Single Market. Maybe this could be secured through something like a “soft” Brexit, meaning that the UK would remain in the Single Market. But if that doesn’t happen – and it looks increasingly unlikely – Scotland will be pushed down the road towards independence. That would be a legitimate choice. During the independence referendum campaign in 2014, Scots were told that if we voted to leave the UK, our EU membership would be under threat. In fact, our EU membership has been threatened by voting to remain in the UK. Scottish nationalists will make that case if we have another independence referendum. However, the Scottish economy is currently in bad shape. The country has a very big public deficit because of the recent fall in oil prices. It’s a bad time to have a discussion about Scottish independence.

In the aftermath of the referendum, some doubted that direct democracy is an appropriate means of decision-making on highly complex issues such as EU membership.

Referendums are not a big part of the UK’s constitutional tradition. It’s very different from Switzerland, for example, where they play a bigger role in political discourse. What worries me is the way that referendums are seen as a way of putting a lid on UK politics – that now that an issue has been resolved, it can no longer be discussed or contested. People argue that you’re not respecting the outcome of the referendum if you try to make the case that the UK should remain. This is problematic, because democracy means that you make decisions in a given time and space. Usually you elect a government, but after a few years, and a change in facts and circumstances, you are entitled to reconsider and re-evaluate. I think that’s the way we should treat Brexit. The referendum result was based on a lot of promises by the Leave campaign that haven’t come to pass. Therefore, it is not illegitimate for people to change their minds after receiving new information, or if they are disappointed by the outcome.

What should be done to restore confidence in the concept of EU citizenship, given that not all EU citizens enjoy their rights to an equal degree?

I’m not sure whether the current construction of the EU is amenable to developing the concept of EU citizenship. In the early days, the individual drove forward the integration project. This was one of the EU’s great normative advantages. A big leap forward, as all EU lawyers know, was the decision of the European Court of Justice in the 1963 case Van Gend en Loos, which said that the Treaties have “direct effect”. Individuals can enforce their rights under European law in their national courts, or even use EU law to strike down government policy. That’s a very emancipatory and novel move. But today, some of the major challenges to the EU, such as the Euro crisis and the refugee crisis, are primarily managed by executives – such as the European Council – and national governments. If we want to recapture EU citizenship, we have to place the individual at the heart of EU integration. We need to design policies that benefit people who stay in their Member State, not just those who are mobile. The tricky part is that some of the concrete benefits for which the EU is very popular, such as the Erasmus programme, or the cap on mobile phone roaming charges, primarily benefit societies’ elites.

One of your colleagues at the Hertie School, Professor Henrik Enderlein, has previously suggested that the UK will still be a member of the EU in 10 years’ time, as it is “impossible to unscramble scrambled eggs”. Do you agree?

I find that prospect literally impossible. It’s a very tempting conclusion from a European perspective, but ultimately the issue will be determined by British politics. A mixture of outlandish scenarios would have to come to pass in order for Britain to remain. Scenario One would be that Theresa May, prior to ratifying any deal for Britain to leave, would call a General Election. The Labour Party, as the main opposition party, would position themselves as the party for remaining in the EU. However, the Labour Party is not in a position to win a General Election and it’s also unclear whether their leader would advocate for remaining. Theresa May has also said that she doesn’t want to have an Election until 2020, and if the process begins in early 2017, it will be over by then. Scenario Two would be that she changes her mind and decides that it’s in Britain’s interests to stay. Given the precarious majority of the Conservative Party in Parliament, she wouldn’t be able to win the support of her colleagues.

You were recently awarded a substantial research grant for the LEVIATHAN project, which will examine the accountability structures of EU economic governance. Do you think that Brexit will encourage any positive changes in this respect?

I am not totally convinced. Despite being an awkward partner, the UK has always cared about accountability and scrutiny. In the future, the German and French motor will become stronger; the Eurozone will head towards greater fiscal integration. Countries such as the Netherlands and the Scandinavian Member States have reason to worry about this, as they previously used the UK as a way to resist the dominance of the other Member States. That is potentially a problem in terms of accountability.

You paint quite a bleak picture…

I honestly don’t see anything positive on the horizon! The most positive scenario is also a very chilling one. Imagine the UK leaves with a “hard” Brexit, becomes a prosperous state, a little like Ireland, with a low corporate tax base, or the Singapore of Europe. This would be a kind of “beggar thy neighbour” economic policy, whereby we attract companies, but they don’t necessarily invest in the people of the UK. Meanwhile, we undermine the tax bases of other European countries. Ultimately, if we became successful in terms of GDP growth, for example, we would be used as an example by populist parties in, say, the Netherlands or Sweden, to argue that you can leave the EU and all will be well – you don’t need the Single Market or integration to be prosperous, which would be a kind of half-truth. We will either be punished for leaving the EU, which might strengthen the integration project, or we will prosper, which could weaken it. We’re damned if we do and we’re damned if we don’t.

That said, the EU could use Brexit as an opportunity to look more closely at itself, think about how it can reform and move closer to citizens. Moving towards a decoupling of national and European citizenship, or away from the idea of leadership by the European Council would make the EU more democratically, legally and politically accountable. If that was a consequence of Brexit, that would be positive, but I’m not holding my breath.

Mark Dawson is Professor of European law and governance at the Hertie School. He holds degrees from the Universities of Edinburgh and Aberdeen as well as a PhD from the European University Institute in Florence. His research focuses on the relationship in the EU between law and policymaking, particularly in the areas of economic governance and fundamental rights protection.

Lisa Gow is Executive Editor of the Governance Post and a second-year Public Policy student at the Hertie School of Governance.