Even in its incomplete stage of implementation, the European Banking Union is an example of the benefits that can ultimately be achieved when national governments transfer part of their authority to the European level.

It is almost ironic that one of the most significant steps in European integration since the introduction of the Euro took place in an environment where the overall project had been brought into question. Eurosceptic parties are becoming increasingly popular, defining achievements such as the Schengen Zone can no longer be taken for granted and the prospect of a country leaving the Union has become reality.

The European Banking Union is a project that has been on and off in the media for the last couple of years, but was never communicated in such a way that people without an interest in finance could or wanted to understand. This may have something to do with the complexity of the issue or the fact that important aspects of the Banking Union are still under negotiation. However, when this is linked to the origins of the crisis, the theoretical value of the Banking Union becomes more apparent and makes a case for the benefits of further European integration. Instead, the media has recently opted to convey yet another dispute between Germany and everyone else about the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS) (Schuknecht 2016).

The European Economic and Monetary Union is an incomplete entity that is still missing a Political and Fiscal Union. The Banking Union is a prime example of what can be achieved when national governments decide to pool part of their authority to satisfy the need for a greater good that they would not have been able to achieve individually, thus bringing Europe one step closer to a more complete and better union.

In these circumstances, the EU should enhance its efforts to communicate the creation of the Banking Union to demonstrate why we ultimately need more Europe.

The bank-sovereign vicious circle

Let us quickly remember how the sovereign debt crisis came about. In 2008, the US financial market crisis spilled over to Europe (for everything that happened before 2008 consider watching “The Big Short”). Tight connections with US banks weakened the balance sheets of European banks. As a consequence, certain European banks came close to bankruptcy, and the government had to step in to bail them out – with taxpayer money. This in turn enhanced sovereign debt levels. As sovereigns themselves came closer to the point of bankruptcy, the domestic banks that typically hold a substantial amount of government debt needed more liquidity from the state and the vicious circle started all over again.

The Irish case is an excellent example of the bank-sovereign vicious circle (or “doom-loop”). Since the introduction of the Euro until just before the crisis hit Irish banks, the Irish debt to GDP ratio decreased from an already staggeringly low level of 31% even further to 24% (AMECO Database,2007). After the US housing bubble burst and subsequent financial crisis, Irish banks where in desperate need of state financial support. The Irish government saw no other alternative than to bail out those banks that were considered “too big to fail”. The increasingly unsustainable outlook of Irish public finances ultimately worsened conditions for Irish banks, and the government was forced to provide even more financial support to these institutions. The Irish debt ratio increased in 2012 to 120%, due largely to fiscal deficits being as high as 32% of GDP in 2010 (AMECO database). In due course, the bank-sovereign vicious circle led to a loss of market access and Ireland was forced to apply for financial assistance in late 2010.

The three pillars of the Banking Union

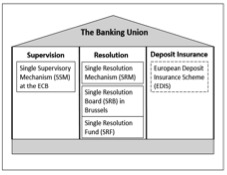

The Banking Union attempts to break up the “doom-loop” by ensuring that no state will again have to use taxpayer money to bail out struggling banks. The aim of this process is to find a private solution for ailing banks either through insolvency or resolution (restructuring). The two cornerstones of the Banking Union already in place are the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) at the ECB in Frankfurt and Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) governed by the Single Resolution Board (SRB) in Brussels. The third, a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), is still currently subject to negotiation.

Since November 2014 the SSM has been in charge of supervising the 128 “significant banks” in the Euro Area, whereas national authorities retain responsibility over the remaining approximately 6.000 “less significant institutions”. Pooling banking supervision at the European level is an important step to prevent national authorities from insufficiently regulating their banks that would increase the risk of a financial crisis, ultimately effecting other European countries. The SSM, for example, has begun to increase capital requirements for European Banks in order to expand their financial buffer and decrease their leverage. This should contribute to a more stable European banking system.

At the beginning of 2016 the SRB was given full responsibility for dissolving ailing banks within Eurozone countries. The basic idea of the SRM is to allow primarily shareholders and creditors to bear the burden of bankruptcy rather than taxpayers. This approach has already been proven to be successful when in March 2015 “Düsseldorfer Hypothekenbank”, a relatively minor German bank, came close to bankruptcy. The Association of German Banks decided to overtake the bank for 1 Euro, including its risks, hoping that to continue the bank would be less costly than the spillover effects from an insolvency onto their own businesses.

If insolvency or resolution is not an option bail out money will be provided through the Single Resolution Fund (SRF), which is part of the Single Resolution Mechanism. The SRF will collect around €55 billion until the end of 2023 and is financed by the banks themselves. Euro area banks are not only forced to finance their own bailout but also have to provide the SRB with a manual of how to resolve it themselves. It remains to be seen how viable the SRM will be when the SRB is confronted with an almost bankrupt bank for the first time.

The Banking Union and European integration

Ultimately, the Banking Union constitutes a necessary response to the Eurozone crisis for national governments plan to hold on to the European Economic and Monetary Union project. But this is, yet again, a project of European technocrats that has not managed to find its way into the minds of ordinary European citizens. National governments and European Institutions have to date not found a way to transfer the benefits of the Banking Union into a more comprehensible degree, restricting them from the opportunity to make a case for further European integration. However, in times where Eurosceptics are closely scrutinizing the European project, the EU cannot allow itself to squander any chance to emphasize a European project that will, if planned properly, yield real economic benefits for the European citizens. In the end, it at least will be an improvement to the status-quo, in which national governments still have to bail out banks with tax payer money.

It must be pointed out that the European Banking Union is still under construction:

- The SRM has not been fully implemented (the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) has not been transposed into national law by all Member States).

- No agreement has been reached on the European Common Deposit Insurance Scheme (Nicolas Véron, 2016).

- There is still the question of bridge financing for the Single Resolution Fund until the end of 2023.

- Finally, and most importantly, there is no fiscal backstop in place. This means tax payer money will still ultimately be used should all other available measures fail (Pisani-Ferry, 2016).

However, even in its currently incomplete stage, it highlights the theoretical benefits of further European integration. If completed properly, the Banking Union will make a significant contribution to developing a more sound financial system and it will bring us one step closer to a more complete and better Economic and Monetary Union. In essence, the Banking Union pools authority to establish something that national governments couldn’t have done individually and will ultimately benefit all Eurozone members. The benefits from further integration (financial stability) outweigh the loss of sovereignty (banking supervision). Under the current state of the integration process, this project could therefore be used as an example for more integration in other policy areas.

Lukas Nüse is a class of 2018 Master of Public Policy candidate at the Hertie School of Governance. He holds a B.Sc. in Economics from the University of Bonn. During his studies, he worked as an intern for the Bertelsmann Stiftung in Brussels, one of the biggest German think tanks, and as a student assistant for a Bonn based think tank. Lukas recently interned with the German Federal Ministry of Finance and is currently doing a professional year in the EU division of the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. His general areas of interest include European economic and fiscal policy, financial supervision and stability, monetary policy and the European labour market.

References upon request.