Recently, investment and trade agreements have been highlighted in popular discourse as controversial. The proposed Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the European Union and the United States has cultivated tremendous public opposition, despite the European Commission’s assertion that the deal could increase the EU’s GDP by 0.5 per cent. Massive public mobilization against the negotiations have taken place in over 24 EU member states since 2011, with over 450 demonstrations in October 2014 alone. The most recent protest in Berlin saw a manifestation of over 250,000 people. Across the world, there is growing consensus that these treaties can have serious implications. Similar rallies took place in New Zealand, Thailand, and Australia against the 2014 Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations. Furthermore, in 2005, protests in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela against the Free Trade Area for the Americas (FTAA) brought negotiations to a standstill.

Common contentions range from the transparency of negotiations to the lowering of trade barriers. However, the most problematic is that all these treaties contain provisions for Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS). Distinct from international law, which allows states to solely bring claims against one another, ISDS allows investors to sue a state on the pretext that a government’s action can affect their investment. As such, private actors have legally challenged multiple government policies in host countries in relation to multiple issues such as, health, the environment, and affirmative action. This has entailed expensive legal bills and involved extremely sensitive issues of public regulation.

For instance, in 2007, European mining investors sued South Africa claiming to be affected by the government´s post-apartheid economic policies. This trial cost approximately EU 6.37 million. In another case, the government of Ecuador received USD 700 million in 2009 following a claim made by an automobile manufacturer. This amounted to around 20 per cent of Ecuador´s foreign exchange reserves that year. In 2013, a tobacco company moved to sue the Australian government against its health policy to remove brand labels off all cigarette packaging. Following, this planned course of attach the Australian government threatened abolish ISDS clauses altogether. ISDS has thus, manifested into a debate over the rights of investor protection and state sovereignty.

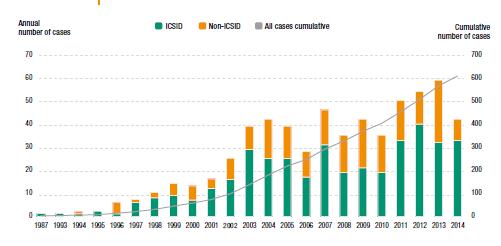

Fig. 1 Number of known ISDS: yearly and cumulative 1987-2014

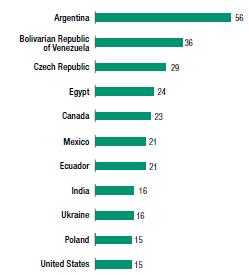

The first BIT concluded between Pakistan and Germany was as early as 1959, however, the introduction of ISDS clauses emerged out of the neoliberal wave of the late 1980s. By the end of 2013, 98 States have been respondents under the ISDS mechanism in a total of 608 claims brought by investors. Of the 356 concluded cases, 37 per cent were decided in favour of the host country and 25 per cent in favour of the investor, and only 28 per cent of the cases were settled. The majority of claims have historically been made against developing countries. However, more recently, there has been a significant rise to the number of cases against developed countries.

Fig. 2 Most frequent respondent states, total number of cases ending 2014

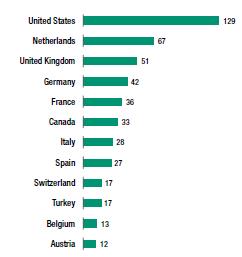

Fig. 3 Most frequent claimant states, total number of cases ending 2014

There has been very little discussion of potential solutions among civil society and non-governmental organizations. President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker stated that the TTIP agreement would do away with ISDS however, in the long run this could deter potential investment. It is also unclear as to the alternative to ISDS. Ultimately, ISDS does have merit,. Investor protection is often necessary in the face of unpredictable political and regulatory environments. Prior to the introduction of ISDS countries resorted to “gunboat diplomacy” to protect against aggravated multinationals. This is hardly feasible today, as it is a rather extreme measure to strain international relations between countries over every commercial in the global business sphere.

Therefore, there has been a turn towards making improvements within the system of ISDS. Broadly understood as structural changes and modification of treaty language. Structural improvements include increasing the transparency of tribunal proceedings and introducing the right to appeal. Altering treaty language by including the introduction of a “right to regulate” clause for host countries has also been suggested. However, the road is fraught with legal challenges. Specifically, transplanting clauses directly from international human rights law into international investment law can often result in these clauses taking on a different meaning due to overlaps in terminology in the two fields.

Lastly, opting for reform does not necessarily mean choosing investor protection at the expense of public interest and vice versa. Rather, an overhaul of our understanding of the very purpose of investment agreements will be important to formulate rules for that international investment which support environmental, social and economic goals while reinforcing good governance.

While the EU may be waking up to the dangers of ISDS only now, the debate over ISDS has been culminating for many years in the developing world. Moreover, despite all the EU’s diatribes and grievances against the United States, it is worth noting that the highest users of ISDS after the United States are companies registered in the EU. The top three claimant countries being the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Germany. This dichotomy is amplified by the fact that the EU has controversially been pushing for a deadlocked free trade agreement with India with the same toxic provisions that it purports to oppose. In the case of TTIP the negotiating partners are on similar footing. Unfortunately, this is not the case for agreements between the EU and developing countries, who often have less bargaining power and leverage in international politics.

According to Andrea Saldarriagas, Lead of the Investment and Human Rights Project at the London School of Economics, an EU policy on investment must reflect European values, for example those of transparency, democracy and participation. “The questions on intra-EU BITs and the debate around TTIP offer a unique opportunity to define a European investment policy that reflects the sophistication of European societies and institutions, while at the same time recognising the needs and specificities of its members. It should therefore include a multi-stake holder process that informs the construction of this policy by understanding the needs of states, the needs of investors and the expectations of societies – and this in the context of the Single Market.” Perhaps in this way, public European debates over the TTIP can go beyond the problems with ISDS and look towards possible solutions, thus joining the discussion taking place at the global level.

Feroza Sanjana is a doctoral candidate at the Berlin Graduate School for Transnational Studies. Her research critically analyses the ideas that form and inform the international investment regime. She has a Master’s degree from London School of Economics and School of Oriental and African Studies London. She has also contributed to the UNCTAD conference on “Reforming investment agreements for sustainable development” held in Geneva in February this year.

Feroza Sanjana is a doctoral candidate at the Berlin Graduate School for Transnational Studies. Her research critically analyses the ideas that form and inform the international investment regime. She has a Master’s degree from London School of Economics and School of Oriental and African Studies London. She has also contributed to the UNCTAD conference on “Reforming investment agreements for sustainable development” held in Geneva in February this year.