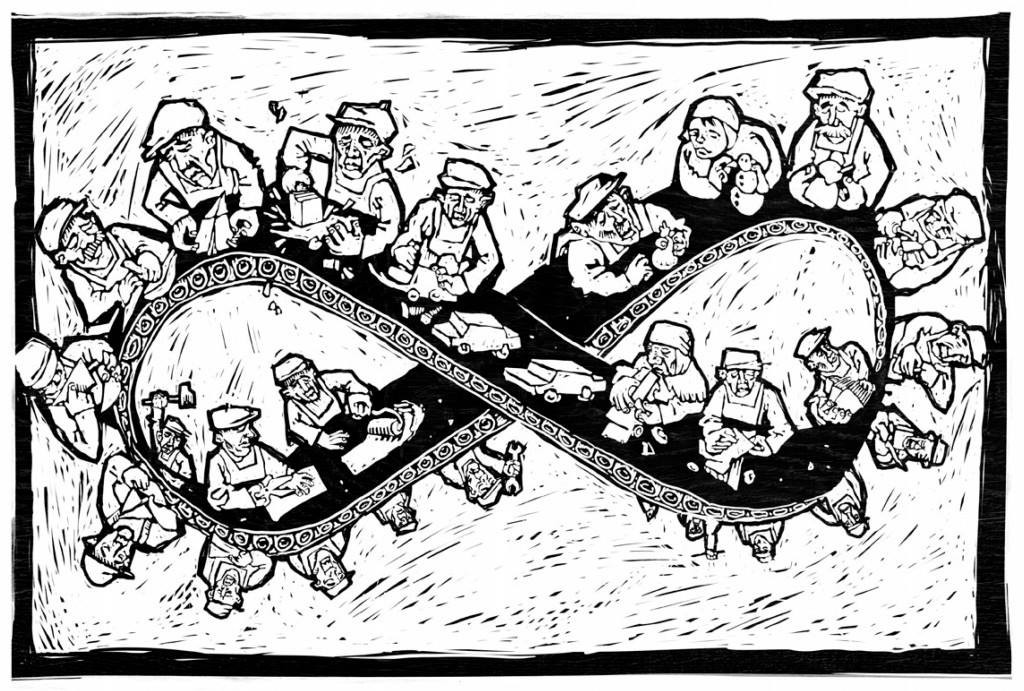

The zero-hours contract, a type of employment relationship which carries no mutuality of obligation between employer and employee, has become an almost entrenched feature of the UK’s post-recession labour market landscape. Dr John Philpott questions the macroeconomic and individual benefits said to be offered by this type of arrangement, suggesting that its increasing use may be linked to the UK’s slump in labour productivity.

A decade ago, few people in the UK knew that employers could hire staff on contracts that do not guarantee a minimum number of working hours. Yet, by the time of the General Election in May 2015, ‘ zero hours contracts’ had become a political cause célèbre. The opposition Labour Party and other leftist minority parties highlighted the practice as emblematic of the economic insecurity popularly associated with the UK’ s much lauded labour market flexibility. Although the victory of the centre-right Conservative Party has, for the time being, removed the prospect of anything beyond very limited regulation of zero-hours contracts, their use is likely to remain a hot topic.

The salience of the issue owes less to the overall number of people currently employed in this way than to the relatively sharp and sustained growth of the phenomenon. The British Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that around 750,000 people in the UK – 2.5 per cent of all of those in work – are involved in one or more of the total of 1.5 million zero-hours arrangements (ONS 2015). While fewer than one per cent of workers were on zero-hours contracts prior to the Great Recession of 2008-9, this form of ultra-flexible on-call working is now used to varying degrees in most sectors of the economy, especially retail, hospitality and public services, including education.

The ONS is uncertain about how much of this measured increase – recorded by the quarterly household Labour Force Survey – is due to economic factors or simply reflects more accurate reporting by people who were unaware of their precise contractual status before the subject hit the media headlines. Insofar as there is a genuine underlying rise, some analysts think this will prove to be a temporary response by cost-conscious businesses to uncertain post-recession trading conditions. If so, the upward trend might at some point stall, or go into reverse. However, the fact that the number has continued to rise year after year despite a solid economic recovery since 2013 suggests to others that zero-hours contracts are becoming a core structural feature of the UK’ s employment landscape.

Should this worry us? The various UK employers’ associations say no, claiming that zero-hours contracts have been unfairly demonised. On this view, the contracts are said to be good for jobs and to add to the happiness of many people working in this way who like the flexibility of choosing when they work; the quid pro quo for no guaranteed hours of work is no obligation to accept work when offered. For example, a large-scale survey by the UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES) finds two-thirds of people on zero-hours contracts satisfied with their jobs (UKCES, 2014). Moreover, even though work is not guaranteed, it is, in most instances, available; according to the ONS, workers on zero-hours contracts usually average 25 hours of work each week.

Nonetheless, critics of the practice argue that the upsides of zero-hours contracts are more than offset by the downsides. By definition, no guaranteed hours of work for zero-hours contract workers mean no security of income. This is reflected in the UKCES survey cited above, which finds that 57 per cent of people on zero-hours contracts find it difficult to budget from month to month. Zero-hours contracts also flout the spirit of legal minimum wage provision, because entitlement to the minimum wage is worthless at times when no work is offered.

Comparatively little attention, however, is given to the broader macroeconomic effects of zero-hours contracts, consideration of which casts additional doubt on their efficacy. People on zero-hours contracts are always nominally in work, adding to measured employment, but not necessarily always at work producing anything, thereby depressing measured productivity. More fundamental still, establishing the employment relationship on as casual a basis as possible makes it far less likely that employers will invest in productivity-enhancing training and development for workers on zero-hours contracts. The UKCES survey finds that 17 per cent of zero-hours contract workers have to fund their own training if they want to progress in the labour market. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that the continued rise in zero-hours contracts since the start of the recession has been accompanied by a slump in labour productivity in the UK.

The negative impact of zero-hours contracts on productivity clearly places a question mark over the value to the economy of the additional jobs that their use has been said to generate. This is especially true when one considers that the impact of zero-hours contracts on unemployment is probably far less than whatever impact they have on jobs. These contracts are most attractive to people without dependents and/or those who do not rely on their zero-hours contract job for their entire regular income – notably full-time students and also older people who may use the occasional bit of casual work to supplement their pension. However, the situation is very different for those unemployed people who need the security of a steady job that pays a regular wage. They are at risk of being effectively blocked out of work if their only alternative to a pitiful but secure welfare cheque is the insecurity of a zero-hours contract job.

Dr. John Philpott completed his Ph.D. in Economics at the University of Oxford and has since acquired thirty years’ experience as an economic analyst. As the founding Director of The Jobs Economist consultancy, he specialises in the labour market, employment trends, human resource management and related public policy issues. Previously, he was Director of the Employment Policy Institute and Chief Economic Adviser to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development in the UK.

Dr. John Philpott completed his Ph.D. in Economics at the University of Oxford and has since acquired thirty years’ experience as an economic analyst. As the founding Director of The Jobs Economist consultancy, he specialises in the labour market, employment trends, human resource management and related public policy issues. Previously, he was Director of the Employment Policy Institute and Chief Economic Adviser to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development in the UK.