Four years after the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear accident and the subsequent shutdown of all nuclear plants in Japan, the Abe government announced earlier this year that it would gradually restart its nuclear energy production, sparking criticisms both locally and internationally. This article uncovers the main determinants of Japan’s recent shift in energy policy. Furthermore, it reminds us that, while the development of renewable energy sources is indeed very promising, caution is still advised.

After the shutdown of all 54 nuclear reactors in Japan in September 2013 and despite the positions of the Abe administration favouring the return of nuclear power production, many were hoping that Japan would become a new role-model for achieving a low-carbon, nuclear-free economy. In the two years that have passed since then, those hopes were gradually replaced by the sober realisation that, even with electricity demand declining steadily, energy supply was not secured. Meanwhile, CO2 emissions have hit the roof.

As the Abe government formulated its energy system reform plan in April of last year – a policy framework aiming to simultaneously de-carbonise the economy, liberalise the domestic supply of electricity and gas, and secure the provision of energy – the implications of such a reform have become subject to intense debate both locally and internationally. Critics have targeted a lack of ambition concerning the development of the renewable energy sector as well as the decision to gradually resume nuclear power production.

Based on these recent developments, it is legitimate to ask ourselves whether an alternative pathway for Japan to de-carbonise the economy was ever realistic in the first place.

In the wake of the Fukushima-Daiishi nuclear accident, the then-governing Democratic Party of Japan (DPR) had already formulated an ‘Innovative Strategy for Energy and the Environment’ in September 2012. This strategy claimed to rely on three main pillars. Besides achieving a nuclear-free economy by 2030, other stated goals included the advancement of the ‘Green Growth’ agenda and the securitisation of a stable energy supply. Some three months later, the DPR lost the national election, which favoured the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) of Shinzo Abe. As a result, the energy reform was rebuilt from scratch. Despite having declared during the electoral campaign that it supported a nuclear phase-out, the newly elected government subsequently contradicted its own previous positions and “decided that the survival of the nuclear power industry was critical to keeping electricity costs low and spurring an industrial recovery”.

While a temporary shut-down of all remaining nuclear reactors was decided upon in September 2013 as part of a push for increased safety, the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has since then advocated for a three-stage reform of the power industry. The centerpiece of the plan is the full liberalization in April next year of the retail electricity market, which has been largely dominated by regional monopolies over the past 60 years. Furthermore, the plan aims for the establishment of a separate organization to promote wide-area electrical grid operation and the separation of power generation and power transmission in 2018-2020. As an additional part of this set of reforms, a separate commission drafted medium-term targets for 2030. Under these targets, nuclear power will account for 20 to 22 percent of the nation’s electricity supply, while the share of renewable energy will rise to 22 to 24 percent.

Putting aside the fact that cheap electricity was perceived by the LDP as a necessity for the success of ‘Abenomics’ as a whole, we need to look at the situation of the Japanese power sector pre-Fukushima to understand why the Abe government rolled back on its stated intent to phase out nuclear production. Until the Great East Japan earthquake in 2011, Japan’s nuclear power plants had 54 reactors producing more than a fourth of the nation’s electricity demand. At the time, Japan was the world’s third-largest producer of nuclear power after France and the US. Nuclear power was furthermore perceived by previous Japanese governments as key to developing the nation’s energy security and its production of clean energy. It was to cover over 40 percent of the country’s energy requirements by 2020, and almost half by 2030. Based on this knowledge, it is clear that investments in renewable energy sources were based on forecasts which were later revealed to be irrelevant after the Fukushima accident.

Two major imperatives emerged from the post-Fukushima situation. First, there was a significant need to cover the energy deficit created by the shut-down of all nuclear reactors. This was to be done with a new energy mix relying on fossil fuels and renewable energy sources. Secondly, achieving this new mix necessitated important energy consumption cuts. Both imperatives were however largely insufficient on their own to formulate a long-term vision for Japanese energy policy. While the former represents more of a short-term and temporary solution, the latter is realistically a very slow and long process. As a result, Japan is now the world’s second largest importer of fossil fuels.

This shift in Japan’s energy mix has had important effects on the economy, society, and the environment. The value of fossil fuel imports increased to 27 trillion yen (around 224 billion dollars) in 2013, 10 trillion yen more than prior to the earthquake. This has resulted in Japan’s largest ever trade deficit of 11.5 trillion yen. Moreover, the average electricity unit price (electric lighting costs) for the average household and the average electricity unit price (electric power costs) for industrial facilities rose by around 20 percent and 30 percent respectively between 2010 and 2013. In addition, following the shutdown of all nuclear reactors, greenhouse gas emissions rose significantly — by 4 percent in 2012 and 1.3 percent in 2013 — raising Japan’s emissions 10.6 percent above the 1990 rate. According to the latest reports, CO2 emissions in 2014 hit a new high with 1.41 billion metric tonnes in comparison to 1.223 in the previous year.

More important perhaps is the failure of the feed-in tariff system to deliver the results that were expected of it with regards to the development of renewable energy sources. In July 2012, Japan adopted a feed-in tariff (FiT) system that obliged utilities to purchase power from renewable sources at a fixed price, inspired by the German model. The effectiveness of the FiT system was undermined by several loopholes and a general lack of binding rules in the legislation, which reinforced existing imbalances in the energy market. These imbalances favoured the incumbent conventional energy producers and suppliers that already were in a quasi-monopolistic situation at the regional level prior to the enactment of the FiT scheme. These shortcomings led the government to cut down on feed-in tariffs levels from 42 to a little over 30 Yen per kilowatt/hour.

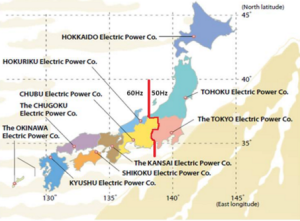

These shortcomings were furthermore amplified by suboptimal grid management. According to Hiranuma, the power grid was fragmented under the regional monopolies of Japan’s 10 “general electric utilities”, resulting in a failure to develop the kind of wide-area transmission system needed to transfer electricity from regions with a surplus to those suffering shortages. This fragmentation of the grid can be particularly problematic (especially for integrating renewable energy sources in the energy mix) when there are two incompatible transmission systems — as has been the case in Japan, where a 50-hertz grid operates in the east while a 60 Hz grid does so in the west (Figure 1).

While the main aims of the reform plan are to ensure a stable and reliable power supply and to break up regional monopolies, these goals are far from being incompatible with de-carbonising the economy in the medium to long-term. Liberalising the retail market is a necessary step for further development of the renewable energy sector in Japan, which until now had been constrained by excessive political leniency toward regional monopolies relying on conventional energy sources. This has played a major role in slowing down the growth of the renewable energy sector.

Figure 1: Japan’s 10 Regional Power Companies by Service Area

Source: The Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan (FEPC)

Furthermore, the targeted energy mix for 2030 is, despite criticisms, possibly the only viable alternative currently at hand for achieving the necessary climate goals. While the IPCC voiced its support in favour of Japan’s projected energy mix earlier this year, recent studies from the International Energy Agency and the Nuclear Energy Agency found that, taking into account economic, political, and demographic pressures, nuclear power will have to remain a driving and growing sector over the next three decades for the world to meet the international goal of limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius.

Figure 2: Levelised Cost of Electricity in Japan for the main energy sources

Source: Berraho (2012)

Finally, even if nuclear power plants were to be gradually reactivated, many will have to be decommissioned in the next two decades as stipulated under the law regarding the life expectancy of nuclear reactors. In this respect, an anticipated phase-out, as opposed to the shutdown of the nation’s entire nuclear fleet all at once, creates a vacuum which renewable energy production can much more realistically fill. A shift of Japan’s policy towards a greener energy mix will need to be done gradually due to the cost of producing electricity from renewable energy sources. As shown in Figure 2, the projected costs in 2030 of producing electricity from solar PV or even offshore wind will still be significantly higher relative to traditional energy sources. Even when taking into account projections on the additional costs of reparation and maintenance associated with nuclear energy production, the latter is still more advantageous in the short-term than renewable energy sources.

This overview of the challenges and constraints facing the Japanese energy transition has shown that, under the present conjectural and institutional circumstances, pushing for a renewable energy revolution or even maintaining the status-quo in the short-term is costly, unsustainable, and puts Japan’s energy security at risk. However, this analysis is by no means an attempt to justify nuclear power production in general. As the case of the German Energiewende shows, it is possible, given certain hypothetical and institutional conditions, to progress towards a de-carbonised economy without relying on nuclear energy. But without any sustainable form of bipartisan support on the issue, a growing economy, or a clear long-term vision for energy policy-making, it would be difficult to envisage the Japanese long-term energy planning following the same route at the same pace as its German counterpart.

Nathan Appleman is currently a 2017 MPP candidate at the Hertie School of Governance. In June 2015, Nathan graduated from King’s College London with a BA in International Politics, during which he notably focused on energy politics and democratic transitions.

Nathan Appleman is currently a 2017 MPP candidate at the Hertie School of Governance. In June 2015, Nathan graduated from King’s College London with a BA in International Politics, during which he notably focused on energy politics and democratic transitions.

References upon request.