Jane Martin, Executive Manager of the Obesity Policy Coalition in Australia, examines the challenges faced in tackling the obesity epidemic in the context of a lax regulatory framework and a constant stream of junk food advertising. She calls for a number of measures at all levels of government, including a sugar tax and clearer food labelling, to steer consumers towards healthier choices.

Australia’s obesity rates are climbing. The most frightening statistic is that rates in women are rising faster than anywhere else in the world. Bad diet, overweight, and obesity are the leading risk factors for poor health conditions in Australia. These conditions lead to a range of preventable diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

No Australian National Strategy on Obesity

Our high obesity rates are due, in part, to the lack of a concerted national strategy to address the drivers of the problem. The current approach from the federal government primarily relies on encouraging individuals to change their behaviour. However, in an environment that promotes poor choices, behavioural change lacks meaningful impact. Meanwhile, Australian state governments are failing to implement effective measures or policies necessary to counter this worrying trend.

Admittedly, this problem is not unique to Australia. Countries with high obesity rates, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, are also struggling to slow and reverse obesity rates and reduce their associated health burdens.

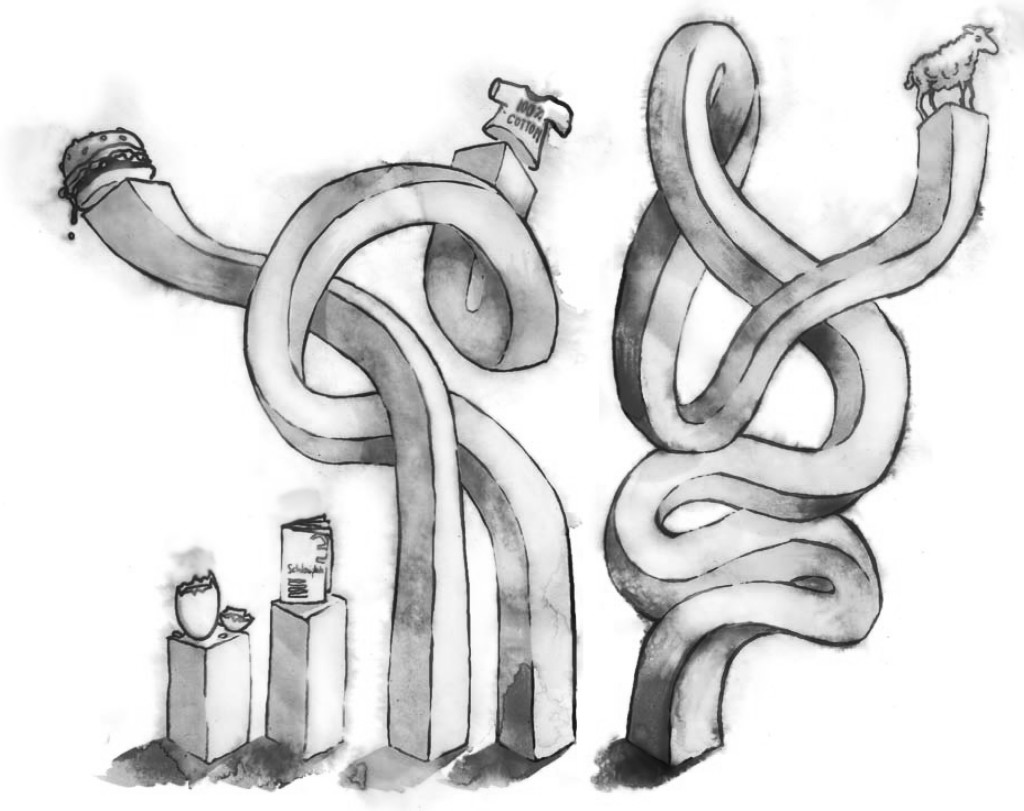

However, what we do know is that there is no magic formula. No single strategy is going to work in isolation. We also know that education is important, but by itself has a weak impact in helping people adapt to an active lifestyle and a healthy diet.

Sugar in the Diet

The evidence is clear: added sugar, particularly in sugary drinks, is a major contributor to overweight and obesity, as well as to poor dental health. In 2015, the World Health Organization published a comprehensive review of the health effects of added sugar in foods, including fruit juice. The review recommended that for the best health benefits, no more than nine teaspoons of added sugar should be consumed daily by men, while women should stick to six.

Further recommendations from WHO’s Regional Office in Europe concluded based on a review of the effectiveness of food taxes, that a tax on sugary drinks has the greatest impact on reducing levels of consumption. A number of countries, such as France, Hungary and Mexico, have followed suit with the introduction of a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages and junk food. Recent polls show Australians do support the prospect of a tax, if it is then used to make healthy foods more affordable.

Currently in Australia, the amount of sugar added to food products is not required to be specified on the label. Evidently, given the impact that added sugar can have on health, it is within the public interest to have this as a requirement for all food products.

Junk Food Marketing

Junk food marketing has become so integrated into our daily lives that we often fail to notice it. Advertising inundates our children; it surrounds them through the sports that they play and follow, targeting them through digital technology such as Facebook, interactive games and YouTube. It embeds itself in school activities through chocolate fundraisers, vending machines, and sponsorships. It follows them home on public transport, and it saturates transport hubs with conveniently placed products and too-good-to-ignore promotions. That is not to mention the traditional promotional tools, such as television. During standard evening programing, unhealthy food is promoted during the ad breaks of the highest-rating kids’ TV shows, such as X-Factor, The Voice and The Block. Contestants on these shows serve as human billboards for junk food products and brands.

The evidence is clear that unhealthy food advertising influences children’s food preferences, purchase requests, and consumption. Therefore, contributing to overweight and obesity as well as poor health outcomes.

In Australia, junk food advertising is largely self-regulated. However, research in Australia and abroad has shown that this model is ineffective in reducing the amount of marketing that children see. As a result, public health experts, including WHO, recommend that the cornerstone of a strategy to deal with the problem of obesity is government intervention to reduce children’s exposure to such marketing.

Solutions: Clear Food Labelling

Health Star Ratings

Easy-to-understand food labelling that guides people in choosing healthier options, is another tool of empowerment. In Australia, the Health Star Rating system was developed using stars to illustrate the healthiness of the food – the more stars, the better. This has been implemented by a number of companies, with star ratings now appearing on approximately 1,000 products. However, to be the most effective it needs to be placed on all packaged foods, in order to ease consumer product comparability.

Kilojoule labelling

In chain fast food outlets, providing information about the amount of energy in foods (in kilojoules) next to products is another way to keep shoppers informed about what they are eating. This scheme has already been implemented in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia. The New South Wales initiative was accompanied by an education campaign and resulted in a significant reduction in the number of kilojoules ordered by customers. Given the large number of meals purchased in these outlets, this approach can have a significant impact across the population.

Solutions: Public Education Campaigns

Public education campaigns, when coupled with other policy measures, can lead to increased knowledge to guide behavioural change in consumers. They are also useful for raising public awareness about a public health issue and gaining support for environmental changes. They can also help to simplify the messages around complex nutritional issues.

The public education campaign LiveLighter is now underway in four Australian jurisdictions – Western Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and the Northern Territory. In 2014, 62 per cent of 25-49 year olds in Victoria were able to recall having seen the campaign in the first six weeks of air. Early results in Victoria have shown that Victorians found the campaign believable (91 per cent) and considered it to have had a strong message (87 per cent). Those who were overweight were more likely to find the campaign self-relevant compared to those who were not overweight (68 per cent cf. 42 per cent). Furthermore, 92 per cent of Victorians support government investment in campaigns such as LiveLighter. Meanwhile, evaluation of a 2013 Western Australian obesity campaign also showed an initial reduction in sugary drink intake among overweight adults.

Evidence from previous public education campaigns (tobacco, UV exposure and road safety) indicates a need for ongoing campaigns within the context of a supportive environment to yield behavioural change. Investing in effective public education campaigns along with robust evaluation is imperative for shifting behaviour towards healthier choices.

An Urgent Need for Comprehensive Action

There is an urgent need for strong leadership and comprehensive action by Australian governments to halt increasing overweight and obesity rates and to avoid the ensuing unsustainable burdens on Australia’s health care system, economy, and society.

A comprehensive package of policies is needed to create an environment that supports healthy eating and physical activity. Isolated or individual-focused initiatives will have little impact on this complex, multi-factorial, societal problem. Action is needed at all levels of government across all portfolios, and by a range of public and private stakeholders. This action should be led by the Australian Government to ensure an integrated and effective approach.

Obesity must become a priority issue for governments and the focus must be on prevention.

Jane Martin has a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) majoring in Public Policy, and a Masters in Public Health. Jane has worked in tobacco control for 20 years, commencing with Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) Australia, as well as the role of Policy Manager with Quit Victoria. Jane has extensive experience in public health advocacy and policy development, and in building the evidence to supporting legislative and policy reforms. In 2011 she was awarded a Jack Brockhoff Churchill Fellowship and undertook the Williamson Community Leadership program in 2013. She has published papers on tobacco and obesity policy reform issues and has presented at national and international public health conferences.

Jane Martin has a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) majoring in Public Policy, and a Masters in Public Health. Jane has worked in tobacco control for 20 years, commencing with Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) Australia, as well as the role of Policy Manager with Quit Victoria. Jane has extensive experience in public health advocacy and policy development, and in building the evidence to supporting legislative and policy reforms. In 2011 she was awarded a Jack Brockhoff Churchill Fellowship and undertook the Williamson Community Leadership program in 2013. She has published papers on tobacco and obesity policy reform issues and has presented at national and international public health conferences.

References upon request.